Daniel Clowes: Q&A (2)

By:

April 9, 2010

In 2002, I pitched a story to Boston Globe’s Ideas section (where I was a columnist) about the fact that Daniel Clowes and Kim Deitch, after years of toiling in relative obscurity, had been published by Pantheon Books. I interviewed Clowes, writing down his answers to my questions — but I didn’t write down the questions, because I figured I’d remember them easily when I transcribed my notes. However, the story was killed, and I never got around to transcribing my notes — until now. Because I can’t recall what my questions were, this Q&A will be presented in the style of David Foster Wallace’s “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men.”

Click here to read my 1999 interview with Clowes.

Q.

A. It’s a great honor. I was very shocked when I got the call from Pantheon. I thought my comics were too idiosyncratic and based in the culture of comics to have any appeal to that sort of publisher. It was amazing to see the attention that David Boring got, when published by Pantheon, as opposed to the attention Ghost World got when published by Fantagraphics. To see the power of what a big publisher could do — it was reviewed all over the place, it sold very well, like 20,000 copies. Fantagraphics had no bookstore distribution then, like it does now — in comic book stores, a Fantagraphics title might sell 5,000 or so.

Q.

A. To me there’s a certain film-noirish romance in cartooning, Many cartoonists of previous generations were sad lonely alcoholics. A lot of these guys got into comics at a young age and were filled with enthusiasm to do great things in this medium, only to get beaten down by a lack of attention. Girls wouldn’t date them. So by the time they’re fifty years old, they’re bitter lonely guys who can only do one thing. They’ve sentenced themselves to life imprisonment — it’s a tragic but beautiful and commendable thing. Wallace Wood, who worked for EC Comics, and the early MAD Magazine — he put a ton of work into everything he did. He stayed up all night, drinking six pots of coffee, in order to fill these things with detail. He killed himself at fifty-five because his kidneys were shot — in any other field, he would have made a decent living, instead of living in horrible poverty.

Q.

A. The comics art audience is almost more avant-garde than I am. Guys into superhero comic art sort themselves into specialized, weird little niches. They’re almost like sex perverts — so specialized in their little field. They have absolutely no interest whatsoever in the kind of things I do — my work is a niche within a niche, and I’m just beginning to finding a way out of that niche into literature. But superhero stuff remains stuck in its little fetish groups. It’s weird that it’s still going on. I used to do events at comic book stores and guys would want to talk about superhero comics — it was odd, to me, that I had to be part of that world, like being a specialist in a weird sex act you’re not interested in at all. When that Spiderman movie came out, journalists called me asking for my opinion. I told them, “Um, I liked Spiderman when I was 13 or 14.”

Q.

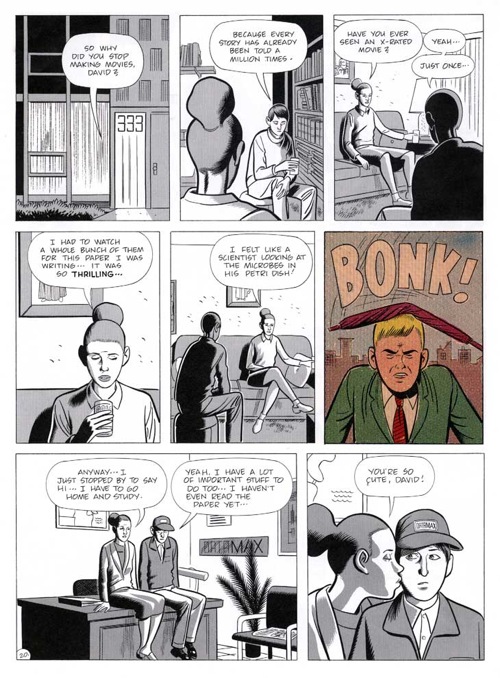

A. In David Boring, I was grappling with taking styles of comics apart and seeing the old Yellow Streak style as something that exists on a purely aesthetic level. I don’t have to incorporate it into my own view of the world in order to see its value. The fragmented comics — I’m making fun of these old comics, but at the same time showing that that’s what comics are — a series of fragments that, when put together, somehow turn into something bigger than all the fragments. At the time I wrote David Boring, I was also working on the Ghost World film, so I was thinking about the different things you could do in each medium. I was conscious of capturing the look of old movies — but I couldn’t use the techniques of movies, which become flat and dull in comics form. So I tried to use movie imagery but tell the story in a way that works in comics, in terms of pacing and how it’s put together.

Q.

A. I was shooting both in content and imagery for that feeling you used to get before cable or VCRs, when there was a real charge to staying up until 2:00 in the morning on a school night discovering a black-and-white movie you’d never seen. I remember seeing Lolita when I was 14. I saw it as a weird love story — I didn’t get that it was wrong — but the movie had a haunting tone that stuck with me for years. I remember seeing The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Buster Keaton movies. I used to search through TV Guide for Japanese monster movies that I could watch late on a Thursday night — there was a great excitement to sneaking behind my parents’ back. It’s not as exciting now, being able to watch whatever movies I want, whenever I want.

Q.

A. He’s supposed to be a hard-boiled cop type. I was trying to make him totally blank — a guy you wouldn’t read any personality into.

Q.

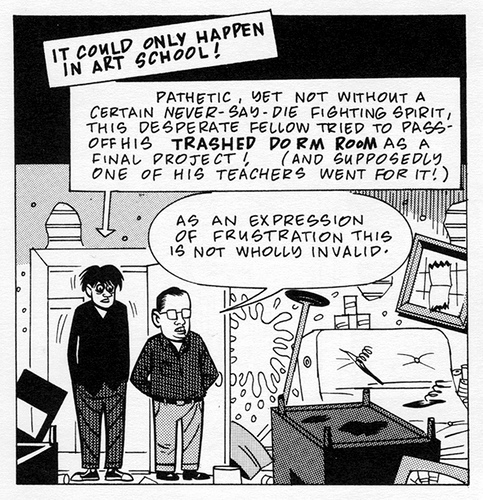

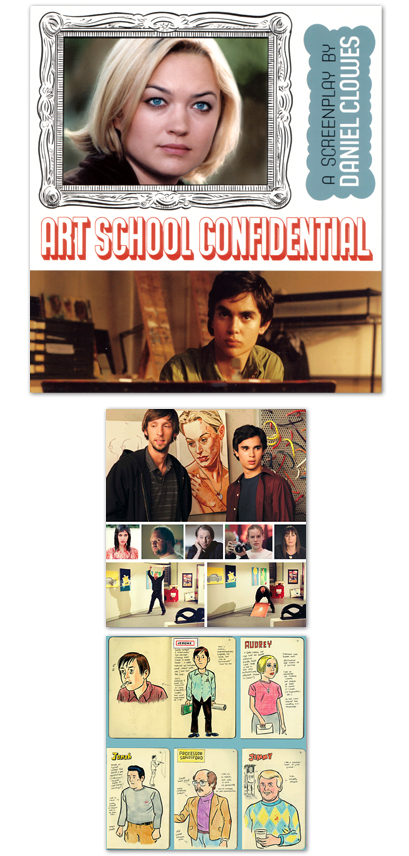

A. I’m finishing the first draft of the Art School Confidential script. It’s 128 pages. But art school is different, now. When I went it was all people locked into a style from the ’40s — Abstract Expressionists, colorful paintings, early conceptual art. I like Rothko, but it’s not my field of interest — not what I wanted to learn how to do. I wanted to learn how to draw, I wanted to learn technical things about how to do work for reproduction. I felt like I’d been swindled. It was great meeting kids my age interested in the things I was, but school itself was worthless.

Q.

A. When I started, I wanted to be a cartoonist. But as I got going, I wanted to be a fine artist to some degree, to learn those techniques, to paint and draw and do etchings. I got to the point where I was going back into cartooning and looking at the world of comics — there was nothing going on. This was in the late ’70s, right before Spiegelman started Raw, and Crumb started Weirdo. The magazine Heavy Metal was coolest things in comics. I looked into magazine illustration, and had a vague plan to do my own comics that would be published as books. If I’d known that some day a big publisher like Pantheon would publish graphic novels, it would have given me a lot more encouragement. Still, there was something exciting about knowing I couldn’t make money as a cartoonist — I knew it would be a weird avocation. Early issues of Eightball are about putting everything I had into it and getting nothing back from it.

Q.

A. I was a bitter young man — seeing friends get art shows by doing a Flintstones-type thing. In the early ’80s people did good stuff with that iconography, especially in Chicago, which had been a lame art town. I mean people doing Lichtenstein-type riffs with modern cartoon characters. They were selling this Judge Dredd stuff for a lot of money. It was frustrating.

Q.

A. The funny thing about the so-called war between cartoonists and musicians that you catch a glimpse of in Bagge’s Hate comics is that the musicians didn’t know about the war. All these grunge guys were into alternative comics and supportive of us. The only bitter and jealous ones were the cartoonists.

Q.

A. Especially in Chicago, all you had to do was leave your house and there was so much visual material. There were so many people you’d pass by — cartoon characters walking the streets. Here in California, people are more well-adjusted and together in their look. You’d get off the plane at O’Hare and see these pasty types. In Norway, I felt like the lowliest homunculus! Chris Ware and I felt like hiding in the hotel room until after dark. Women who, in America would be an unapproachable supermodel, would come to our signings in Norway — totally oblivious to the fact that we were barely able to hold the pencil in their presence.

Q.

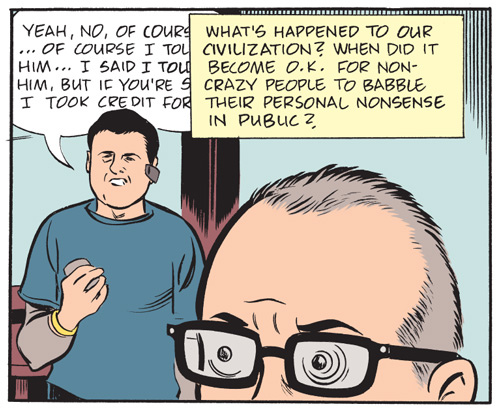

A. He’s one of those guys you run into — like the guy in the comic store who has a lofty opinion on every subject. After the Ghost World movie, like an idiot I’d read these verbose blowhards deconstructing it.

Q.

A. Somebody just sent me some of the superhero comics I’d talked about in interviews, the ones I read as an adolescent. It was weird to see them again. They’d changed so much in my memory, into something much more interesting than they actually were. The Superman comic where he becomes some kind of demon with a crazy leering face — I remember hiding that one in a stack of National Geographic magazines so I wouldn’t accidentally look at it. It’s amazing to see, now, that although the image hasn’t changed, I’ve constantly updated it in my unconscious so it would remain horrible.

Q.

A. I started reading comics before I could actually read. I’d piece together the stories, making up my own narratives based on the sequence of images. My stories were always more horrifying than the real ones turned out to be. I remember a panel in which Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm is kissing a horse — I though the horse was eating her face. All these cartoons from my childhood that I’ve desperately wanted to see — partly because my parents had no interest in photography, so my childhood is unrecorded — turn out to be disappointing when I do track them down. For years, I tried to find a cartoon about a character named Super President. I thought I must have invented the character, but then I finally saw it… and it was a terrible Scooby Doo-type cartoon. Some pop culture is timeless — but the junk from my childhood is worthless.

Q.

A. My brother was encouraging. He was much older, so he was critical of my work — he’d tell me to study anatomy. Not my father. When my grandmother told my dad I wanted to be a cartoonist, he said, “Good God, I hope not.” My mom didn’t object, and she never threw away my comics. I started drawing very early, before I could read. I had comic characters speaking in world balloons, but the letters were chicken scratches. I was into speech balloons as graphic elements. I have comics dreams all the time where it’s me drawing something, and I’ll read over it and it makes no sense. I wake up and try so hard to recapture the exact words and images but I can tell I’m censoring and editing it with my conscious mind. I’d give anything for a computer printout of my dreams.

Q.

A. I first saw Kim Deitch’s stuff when I was 15 — he did Corn Fed Comics. I used to see his stuff in Arcade. I was always a fan of his — he’s one of those guys who kept doing what he did despite the fact that there wasn’t a market or big audience for it. He kept getting better and better. You’d notice the next thing was a huge leap forward from the last thing. I loved the way he involved you in the story. He created his own world, with its own architecture, its own rules of perspective and anatomy. His style so distinctive and yet so communicable. You know what every line means, and where you are in the room, even if it’s not in typical two-point perspective. Only the really great cartoonists can charm you into liking them through their work. Deitch’s work is so charming, it makes you want to write him a letter.

Q.

A. I read Sunday comic strips, but I could never follow the continued ones. Dick Tracy wasn’t in the Sun Times. I was into Peanuts and Dennis the Menace. Sunday strips weren’t all that exciting — they seemed like weird old relics from the past, out of gas. The new guys were imitating an old style. Today it’s even worse — just a parody of bad cartooning. It fills me with despair to see people reading the funnies — with a look of dull disgust, dull disinterest.

Q.

A. Yes, it is a thing — a lot of cartoonists have the older brother influence. My brother wasn’t around so much but his influence was everywhere. His room was filled with the stuff of dreams — hundreds of science fiction digests with weird covers, hundreds and hundreds of comics, model airplanes and monster masks, so ripe with imagery. I was always trying to create something that would fit in that room, that he would approve of. Crumb talks about how he wasn’t interested in comics, but his brothers inflicted it on him — he had a schedule that he had to meet. He got so hooked into it he never stopped.

Q.

A. I was reading a lot of books by Gershon Legman. He was a bibliographic researcher with the Kinsey Institute, the world’s number-one erotic folklorist, he published the definitive collection of dirty limericks. He wrote a treatise about comics in the ’50s that was deranged and hilarious, a great little tract about the hippies. Legman claims he finds the dirty jokes very sad — the teller was a neurotic, to be pitied. He died recently.

Q.

A. Yeah, the end of the world, stuck on an island. I spent my childhood obsessively watching Gilligan’s Island. I love the idea of paring everything down — right down to two palm trees and a little lagoon.

Q.

A. I’m most impressed with Chris Ware. He’s the guy who I sort of look to, to see what he’s doing to keep it exciting in the world of comics. He’s hard to beat. I’m interested in Charles Burns, the Hernandez Brothers, the usual guys. I’m waiting for someone to emerge from the crowd of younger cartoonists, someone coming out of art school rather than the comic shop. There does seem to be a willful decision to do the opposite, not necessarily of me, but my generation’s comics — which are apparently too labor-intensive. Friedman, Deitch, Burns, and Ware are labor-intensive — a lot of the new stuff I’m seeing is very sloppy and minimalistic. Which can be good at times, but tends to be sort of crutch to indicate some sort of humility and humanity that it doesn’t necessarily indicate. It’s like playing a purposely out-of-tune guitar. It only works when one guy does it.

Q.

A. One of the baser reasons I decided to do that movie was that I’d always felt there were comics among our little crowd that were better written than 99 percent of Hollywood moves — so here’s my chance to see if you could turn one of these comics into a movie. Would it be dismissed as a “comic book movie”? it was gratifying to see that the majority of the response was very positive. They said, “Can you believe this was made from a comic book?” That’s insulting in a way, but not so bad. You can never get people praising your work for the right reasons — they’ll never say exactly what you want them to say. If it happened, there would be no traction in my thinking. It would defeat the purpose of art for me to hit it that exactly. But with Ghost World, for the first time in my life I got to read 2,000 reviews of a single thing I’d done. Which allowed me to look at the movie in general way — the reviews were an indicator of what worked and what didn’t work in a general sense.

Q.

A. There were people who liked aspects of it and people who didn’t. There was a division between those who liked it as comedy or satire and weren’t interested in it as a story, and those who hooked into story — for whom the comedic elements were not important. That was a big schism we had throughout the process, asking ourselves what we wanted to see in the movie. Was it a comedy or a drama?

Q.

A. It hasn’t made my life worse. It’s not like I’m actually in the movie — I never get recognized in the street. I’ve had many opportunities come from it — well-paying, though not what I’d want to do. But this may be my only opportunity to make any money. I once heard Buck Henry made a fortune as a script doctor — getting paid a ton of money for two weeks’ work sounds like the easiest thing in the world. So I told my agent, and the first thing I got was a Julia Roberts-type movie, about a hard-working girl going to get married. I had no idea what to do with it. I couldn’t improve on it in a million years. My idea of improving it would to be have a guy come in with a flamethrower and incinerate everything in the movie, and we could watch the ruins smolder for the rest of the time.

Q.

A. You get spoiled doing your own comics for so many years. All the projects since Ghost World have been self-generated — like the Art School Confidential script. I’d like to keep making movies — it was really exciting and fun. I thought it would be dreary and horrible, but I’ve forgotten all the bad parts. I stayed on set from 6 a.m. to midnight. It’s fun to work with people who are really excited about something. I’ll do it until something turns out really horrible. The danger is you get addicted to that money and keep making things even if they’re lousy. Guys in Hollywood are like guys doing superhero comics. Jack Kirby was an original, but now we’re fifteen imitations away from that.

MORE CLOWES on HILOBROW: Joshua Glenn’s 1999 Q&A with Daniel Clowes | Joshua Glenn’s 2002 Q&A with Daniel Clowes | Josh also has an essay, “Against Groovy,” on Clowes’ anti-boomer ferocity, anti-hipsterism, apocalyptic fantasy, and trashy messianism, in The Daniel Clowes Reader.