Cross-post (1)

By:

September 19, 2019

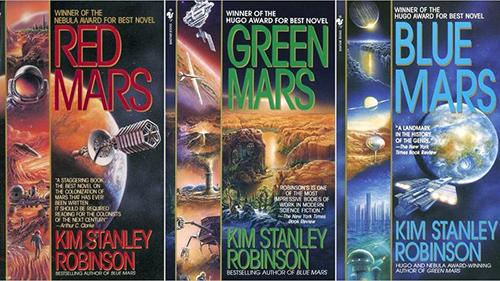

I’ve begun re-reading the Mars Trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson. I’ve been listening rather than reading: revisiting by having a story I already know read to me. This following chunk of a paragraph stood out, and I hit pause on the audiobook so I could locate the exact words. It’s an insightful depiction of the interaction of two individuals in space-suits (Mars-suits?) as they travel across the planet’s surface:

Michel drove the jeep and listened to Maya talk. Did conversation change when voices were divorced from bodies, planted right in the ears of the listeners by helmet mikes? It was as if one were always on the phone, even when sitting next to the person you were talking to. Or — was this better or worse — as if you were engaged in telepathy.

In case you haven’t read the series, it might help to know that Michel is the lonely French psychologist assigned to the 100-person crew setting up camp on Mars at the start of the first book, and that Maya is a captivating and highly driven Russian member of the international assortment of captivating and highly driven characters who populate the novel and the planet.

A few paragraphs earlier, the narrator set the stage for this depiction — two people next to each other, and also quite isolated from each other — as follows:

Michel asked the questions that a shrink program would have asked, Maya answered in a way that a Maya program would have answered. Their voices right in each other’s ears, the intimacy of an intercom.

The way the technologically mediated conversation assists in dehumanizing the characters, turning each into a “program,” is further emphasized by that verb-less standalone clause that comes immediately after. The impact of the observation is further heightened because just two pages earlier still we were told:

…intimacy consisted of talking for hours about what was most important in one’s life.

Robinson (or Stan, as he likes to be called, as I learned when I interviewed him over the course of several conversations a few years ago: “The Man Who Fell for Earth”) always gets deserved credit for the scientific knowledge and imagination he brings to his depiction of how Mars might be terraformed, how it might be made habitable by humans. What makes the novels really work, though, is his awareness of technology at not just an industrial or societal level, but at an interpersonal one as well: how technological change impacts the individuals as much as it does the planet. To remake Mars is to remake ourselves.

Marc’s original post on Disquiet: Listening to and in the Mars Trilogy

The Disquiet blog: https://disquiet.com/

Marc on Twitter: @disquiet