BROKEN KNOWLEDGE (4)

By:

October 16, 2025

University of Toronto philosopher Mark Kingwell and HILOBROW‘s Josh Glenn are coauthors of The Idler’s Glossary (2008), The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011), and The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021). In 2022, they engaged in an epistolary exchange about science fiction. Via the series BROKEN KNOWLEDGE, the title of which references Francis Bacon’s philosophy, HILOBROW is pleased to share a lightly edited version of their exchange with our readers. Also see Josh and Mark’s previous exchange 49th PARALLEL.

BROKEN KNOWLEDGE: FIRST CONTACT | WHAT IF? | A HYBRID GENRE | COUNTERFACTUALS | A HOT DILUTE SOUP | I’M A CYBORG | APOPHENIC-CURIOUS | AN AESTHETICS OF DIRT | PAGING DR. KRISTEVA | POLICING THE GENRE | FAMILIAR STRANGENESS | GAME OVER | THE WORLD VIEWED | DEFAMILIARIZATION | SINGULAR CREATURES | ALIEN ARCHAEOLOGIST | THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF SCREEN-TIME | HOMO SUPERIOR | EVERYTHING IS US.

15th September, 2022

TORONTO

Darth Vader, huh? Nobody who met you now would believe that, would they? Or would they?

I won’t indulge my own list fetishism right now, but all the writers you mentioned were part of my early reading too. Heinlein and Clarke were favourites of mine as well. I also liked the early stuff that predates SF proper (if there is such a thing): Jules Verne and H. G. Wells most obviously. I never thought of myself as a scholar of SF but, looking back, I have written quite a lot of academic work at all levels about speculative fiction — papers in high school, a senior thesis in undergrad about post-apocalyptic fiction, and a master’s dissertation on utopia and dystopia. The novels I mostly worked with — Miller’s Canticle, Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, Bernard Malamud’s God’s Grace, among others — are all fine pieces of fiction in any light (especially Hoban). I was of course influenced along the way by what I imagine remains an obvious reading-list double-play in schools: taking in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Huxley’s Brave New World back to back. Instructive, if a little ham-fisted. I came to appreciate both writers more in their other modes, Orwell as a political essayist and Huxley as a Waugh-like social satirist (Crome Yellow is hilarious in places). I also will never forget the philosopher Richard Rorty’s judgment that O’Brien in Nineteen Eighty-Four, that exquisite psychological torturer, is a portrait of what becomes of intellectuals under autocratic regimes.

Since you included a shout-out, I’ll offer one too. I had a great English teacher in high school, Johnston Smith, and he was the one who suggested both Dune and A Canticle for Leibowitz to me. I went to a Jesuit boys’ high school, and everything had to have some sort of religious connection. Well, not everything. But I credit this education with a kind of spiritual imagination, whatever grasp of logical reasoning I retain, and a lasting taste for the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

We can talk more about this further along, but I’ve been struck over the past ten years or so by my interest in returning to SF as leisure reading. I hadn’t read any for a long time, really since I finished my master’s degree at Edinburgh in 1987. Then, partly inspired by our shared group of friends, I returned to it. I read Gibson and Stephenson, then Iain M. Banks (such brilliant spacecraft names and gameplay), more recently Ann Leckie (mentioned already), Emily St. John Martel (Canadian!), and the wonderful Thrawn books by Timothy Zahn in the sprawling Star Wars universe (they’re the only good ones). I’d say SF remains on my radar still, but most of the time, when I want non-literary fiction — if that’s even the right term — I prefer spy thrillers and hard-boiled detective stories. Naturally I have a soft spot for the hybridized mash-ups of these: PKD, obviously, but also Jonathan Lethem’s almost forgotten Gun, With Occasional Music and Asimov’s excellent human-AI murder-mystery tales, starting with The Caves of Steel. (This is where, incidentally, Asimov first fictionally notes his celebrated, or notorious, Laws of Robotics.)

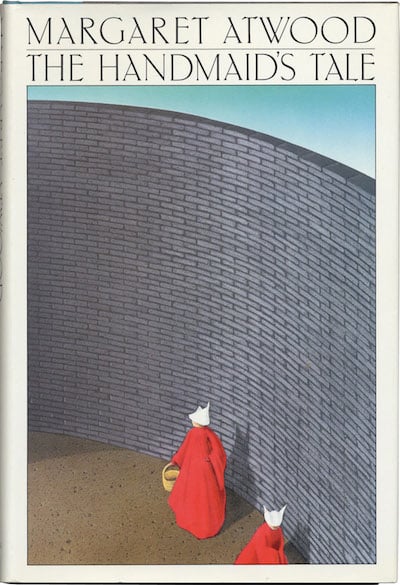

But let’s bite the bullet on hard cases, as you suggest. I mentioned Atwood. She may be taken to be simply switching gears, between the social naturalism of the Toronto novels and the obvious SF of the Oryx and Crake books. But what about The Handmaid’s Tale? Once we allow counterfactuals on real-world history we have to consider Dick again, of course (The Man in the High Castle) but also Philip Roth (The Plot Against America) and P. D. James (Children of Men). Are those cases hard enough?

Last thought: I seem to recall a line from Atwood where she said that there is a clear division between science fiction with monsters/robots and science fiction with no monsters/robots. This isn’t quite the same as the traditional hard/soft division, but it might be worth discussing. Is truly literary SF barred from using what we used to call BEMs (“bug-eyed monsters”) and killer androids?

Mark

ALSO SEE: Josh’s BEST 250 ADVENTURES of the 20th CENTURY list | Mark on BATTLESTAR GALACTICA and THE HONG KONG CAVALIERS | Mark and Josh’s exchange 49th PARALLEL.