THE FALL OF MERCURY (4)

By:

October 4, 2025

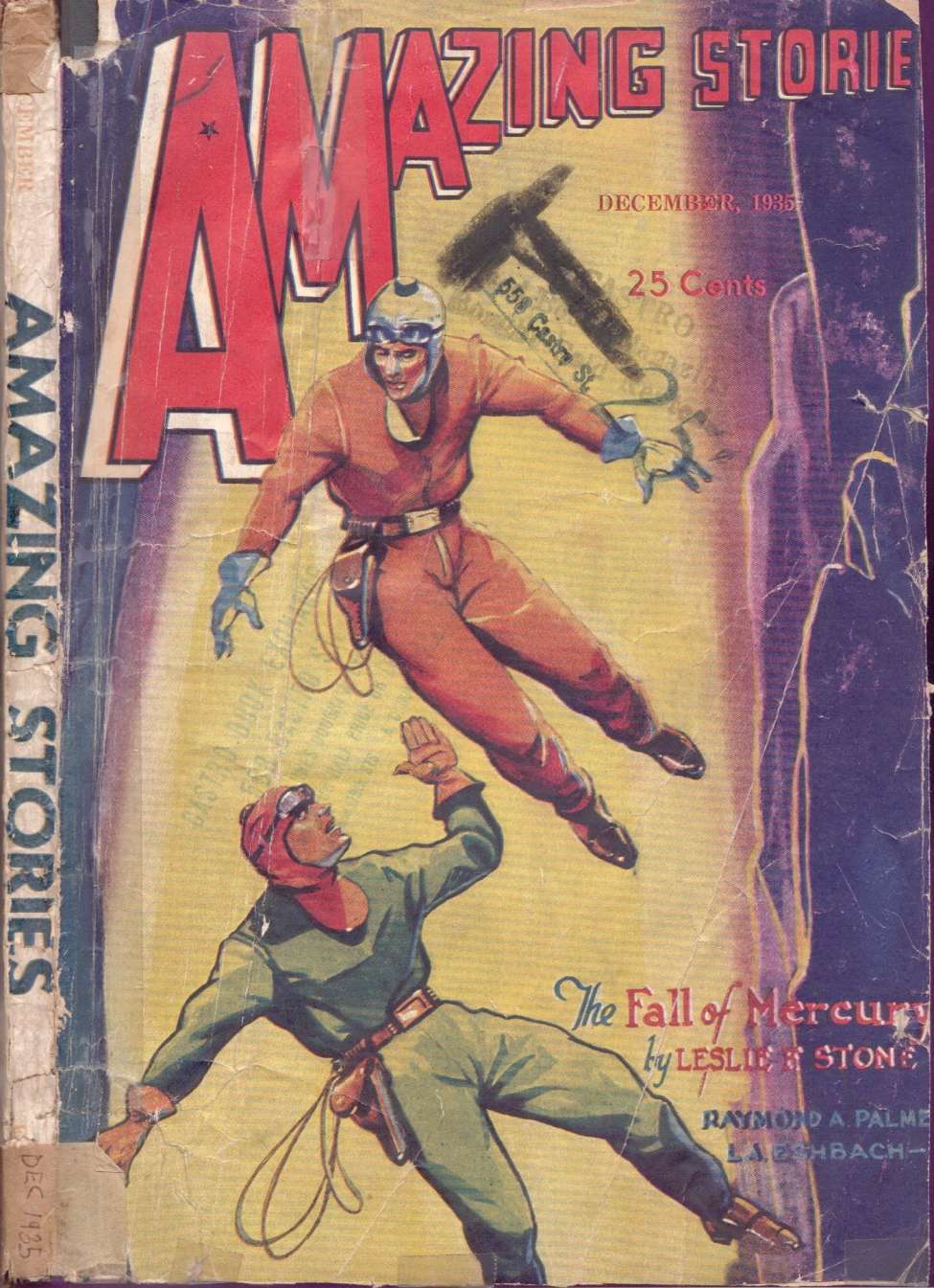

Leslie F. Stone was one of the first women science fiction pulp writers; her stories — including “The Fall of Mercury” (Amazing Stories, Dec. 1935), in which a Black hero uses super-science to destroy a white race bent on conquering the solar system — often featured female or Black protagonists. We are pleased to serialize this story for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12.

CHAPTER FOUR

Prisoners

The room had the appearance of a laboratory with its vast array of various types of apparatus and queer machines. It was possibly a thousand feet in length and almost as wide with a ceiling fifty feet above. The most outstanding objects in the great chamber were the long rows of tremendous pear-shaped tubes, in which purple fires were at play. Not all the tubes, of which there were easily several hundred, were of the same height, but ranged from twenty to almost fifty feet tall. On the floor, apparently, without plan were set machines, some huge things reaching above our heads, some so tiny that their features were scarcely visible to us. And, in the midst of these giants of science, stood the small group of Mercurians who were our hosts, midgets dwarfed in the immensity of the room and of the machines.

There were five of them. Midgets, and strange though their appearance, strange the dead-white of their complexions, the square set of their bodies, their single eye and hunched double-shoulders carrying two pair of arms to our one pair, it was not these features that were so astounding to Forrest and myself. It was their unusual size. The people of Ceres are termed Lilliputians by their larger neighbors since they are but three feet high as the general run; but they were giants beside the men of Mercury! Not one of the five was more than a foot high, and several were a few inches under. These mites our captors? Incredible!

With the first shock of seeing full-grown beings so tiny we gazed curiously upon them. That they were of the genus Homo was evident at first glance; at least, they were bipeds. I have already mentioned the fact of their plurality of arms; their single eye. The body was thick, almost drum-like while their legs were round and straight without shapeliness, their feet seemed toeless, clubbed. Certainly they were the most graceless creatures it had ever been our fortune to meet; and to add to their ungracefulness they wore a sleeveless, straight-line dress hanging awkwardly to the knee. The dead white hue of their skin added much to their repulsiveness, and no other word could fit them better than hideous. The head was long and oval; the eye, white like the rest of them, had only the black pupil to relieve the monotony of the face that seemed dull, expressionless to us. Yet there was intelligence in those high foreheads, the delicate mold of highbridged noses, the sensitive outline of each feature that bespoke sensibilities developed to their highest degree. On the other hand, there was nothing about them to invite friendship. They had, to use a slang expression, a “dead-pan.”

As we studied the Mercurians they in turn gave us the “once-over”; and there was no telling by their faces what they thought of us. But I don’t imagine their opinion was any more complimentary than our own. One of their number took upon himself the duty of spokesman for the group. And the language he spoke was the Esperanto of the Federation, delivered in a harsh voice, high and squeaky. Since he spoke without any show of emotion his tones were necessarily lifeless and monotonous; singsongy. Forrest and I had to incline our heads to hear him clearly.

“Beings of Tellus,” he began, “know that without the Forces of the inner world of the First Planet you would even now be suffocating within the confines of the Venerian Whirlpool. Our force succored you, and brought you here to safety. We ask no gratitude of you. we wish only that as your saviours we have property right to your bodies and being to do with you as we see fit. We ask no allegiance, for we appreciate the fact that you would not give it. We tell you this only that you should know an attempt to escape our world will bring your immediate death. You understand?”

Understand? We understood only too well. And one can picture how flabbergasted we were at this strange speech. Was ever there a stranger welcome from one people to another? Certainly this was not the sort of reception to which we had looked forward. The very tone of that cold voice magnified the meaning of the words a thousand times. We were prisoners and were not to expect largess from our captors. Glancing about the strange laboratory I realized that we were in the tightest spot of our career. Escape? Through stone walls?

Forrest was first to regain his faculties and reproachfully addressed the tiny creature before us. “We duly appreciate your timely intervention in our behalf, Men of Mercury, but perhaps you misunderstand our motives in attempting to reach your world. In the first place we were merely explorers, adventuring for our own enjoyment, and in behalf of the Federation. You speak the code of our Federation; therefore, you must know something of its workings. We come in the spirit of true friendship, to offer to your world, if you will accept it, the fellowship of the Federation of the outer worlds, and to the …”

The little man would not allow Forrest to complete what he wished to say, but made a deprecating gesture, as if what Forrest told him was not news; was, in fact, hardly more than the prattle of a child.

“What you say is of no interest here,” he observed. “We of Mercury, as you deign to call our world, are well acquainted with the precepts of the Federation. Your mind as well as the machinations of your Federation are as open books to us. We have studied the peoples of the outer worlds, watched them struggle into being from savagery to their present state of quasi-civilization. We have seen the establishment of interplanetary commerce among you. In fact, your meagre accomplishments affords us interest of a sort — amusement, rather — but we are content that your Federation believe Mercury a dead world, useless to explore or exploit. That is until the Time comes to change it all. We know the puny powers invested in your worlds, your lust for more worlds to conquer; but we prefer our own seclusion! Were it our desire to wipe your millions off your world’s face we could do so; but we have other plans — we — but, there, enough of this. You…”

I had listened to this tirade long enough. Every word the little beast had uttered stung me to the quick. “Say,” I cried belligerently, “‘enough of this’ is right. What the devil are you getting at? I don’t like your innuendoes or your face, you runt, you. We’re free citizens of the Federation, and unless you release us immediately we’ll…”

An ugly smile slit the face of the Mercurian. “Just what do you intend to do, Bruce Warren?”

Yes, what could we do? My anger subsided like a pricked rubber bladder. I think it was the sound of my name on the lips of the midget that broke the back of my rage. It made me realize what we were up against. Beings with more than ordinary intelligence; beings who read a fellow’s mind by looking at him. The Whirlpool had taken us, and unless a star-gazer had actually seen us dragged from the Spot by our captors, our world would believe us gone. No doubt we were already reported among the dead. I grew ashamed of my outburst, suddenly feeling as if I hardly cared what was to happen to us. Let our captors do their worst!

With what followed it is surprising that the Mercurians had seen fit to acquaint us with our fate. I think it was merely their own arrogance, their desire to crow over men five and six times their own height, that had prompted them into giving us that audience. But they were through with us now. They had had their fun.

Paying us no more attention, our “host” turned to one of his compatriots and spoke a few words in their own language. In answer the tiny man strode over to a desk so small as to have escaped my notice before. It looked like a child’s play-block, only there were a number of small knobs and dials on its top. The Mercurian depressed a number of knobs and, what ho! Forrest and I were once more in the grip of the powers that had seized us on our strange entrance to this strange world. Again we were powerless to make a motion of our own.

No, I was wrong. We could move our legs, but only at the will of the power behind our backs, that propelled us across the wide room toward a circular opening facing us. It was the mouth of a short corridor, and at its end was a great, circular, bronze door that opened to our approach. I felt more than a fool to find myself expertly pushed about by people so tiny as to appear ludicrous in my eyes. But they proved their dominance over me, and I learned the bitter truth that size means naught when the brain is great.

Through the bronze door we found ourselves faced with its twin on the opposite side of a small square chamber completely bare. It seemed odd we should find rooms and doors built to our height in this world of midgets. There was no means with which to gage the age of the door, for their material may have been new that very day or age-old. It showed neither age nor an exacting newness. The first door had closed on our backs, but the second door had not moved. Now through our air-suit ear-phones we could hear the hiss of air in the chamber about us, as in an air-lock; then the second door before us flew open.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.