PRINCESS STEEL (1)

By:

July 17, 2025

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote “The Princess Steel” between 1908 and 1910; it remained unpublished during his lifetime. As usual, the author was exploring philosophical and sociological views — in this case, about the pitfalls of industrial capitalism and the possibilities of revolution. The story was originally titled “The Megascope,” referring to a device allowing one to see through time and space. (John Jennings has named his comics imprint Megascope in honor of Du Bois’ novum.) HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize the story for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5.

“It is perfectly clear,” said my wife, pointing to the sign on the door. “It is perfectly absurd,” I answered and yet there it stood written: “Prof Johnson, Laboratory in Sociology. Hours 9 until 3.” We were on the top story of the new Whistler building, or rather tower, on Broadway, New York, and we had come on account of a rather queer advertisement which we had seen the night before in the Evening Post. It had said: “Professor Hannibal Johnson will exhibit the results of his great experiments in Sociology by the aid of the megascope at two tomorrow. A few interested parties will be admitted.”

Now my wife and I were interested in Sociology; we had studied together at Chicago, so diligently indeed that we had just married and were spending our honeymoon in New York. We had, too, certain pet theories in regard to sociological work and experiment and it certainly seemed very opportune to hear almost immediately upon our arrival of a great lecturer in sociology albeit his name, to our chagrin, was new to us. I was disposed to regard it as rather a joke but my wife took it seriously. We started therefore early the next morning, ascended to the forty-third story or rather “sailed up” as she said, chaffed each other a bit and laughed until sure enough we came to the door.

We knocked and entered and then, scarcely looking at the man at the door, we uttered an exclamation of wonder. The wall was dark with velvety material shrouding its contents in a great soft gloom except where, straight before us, the whole wall had been removed leaving one vast window full 40 by 20 feet, and through that burst suddenly on us the whole panorama of New York. We rushed forward and looked down on seething Broadway. “The river and cliffs of Manhattan,” said my wife. Then with one accord, bethinking ourselves, we turned to apologize to the silent professor and with surprise I saw that he was black.

It never occurred to my little Southern wife however that this was aught but a servant. She simply said, “Well, uncle, where is professor?”

“I am he,” he said, and then it was her turn to be not only surprised but rather disagreeably shocked.

He was a little man in well-brushed black broadcloth with a polished old mahogany face and bushy hair; he stepped softly and had even a certain air of ancient gentility about him. His voice was like the velvet on the walls and his movements precise and formal. One would not for a moment have hesitated to call him a gentleman had it not been for his color. His voice, his manner, everything showed training and refinement. Naturally my wife stiffened and drew back and yet she felt me smiling and hated to acknowledge the failure of our expedition. I was about to suggest going when I noticed that what I had taken to be velvet-covered wall was really the velvet-bound backs of innumerable tall narrow books all of about the same size. I was struck with curiosity. “You have a fine library,” I said tentatively.

“It is the ‘Great Chronicle,’” he said, motioning us gently to chairs; we cautiously sat down.

“I discovered it,” he said, “twenty-seven years ago. This is a chronicle of everyday facts, births, deaths, marriages, sickness, houses, schools, churches, organizations, the infirm, insane, blind, crimes, travel and migration, occupations, crops, things made and unmade — just the everyday facts of life but kept with surprising accuracy by a Silent Brotherhood for two hundred years. This treasure has come to me, and forms,” he said, “the basis of my great discovery. See.” We looked round the room — there were desks and papers, machines apparently for tabulating, a typewriter with a carriage full five feet long, and rolls of paper with figures; but past these he pointed to a great frame over which was stretched a thin transparent film, covered with tiny rectangular lines, and pierced with tiny holes. He pulled his chair nearer and spoke nervously and with intense preoccupation:

“A dot measured by height and breadth on a plane surface like this may measure a single human deed in two dimensions. Now place plane on plane, dot over dot and you have a history of these deeds in days and months and years; so far man has gone, though the Great Chronicle renders my work infinitely more accurate and extensive; but I go further: If now these planes be curved about one center and reflected to and fro we get a curve of infinite curvings which is—” — he paused impressively — “which is the Law of Life.” I smiled at this but my wife looked interested; she had apparently forgotten his color.

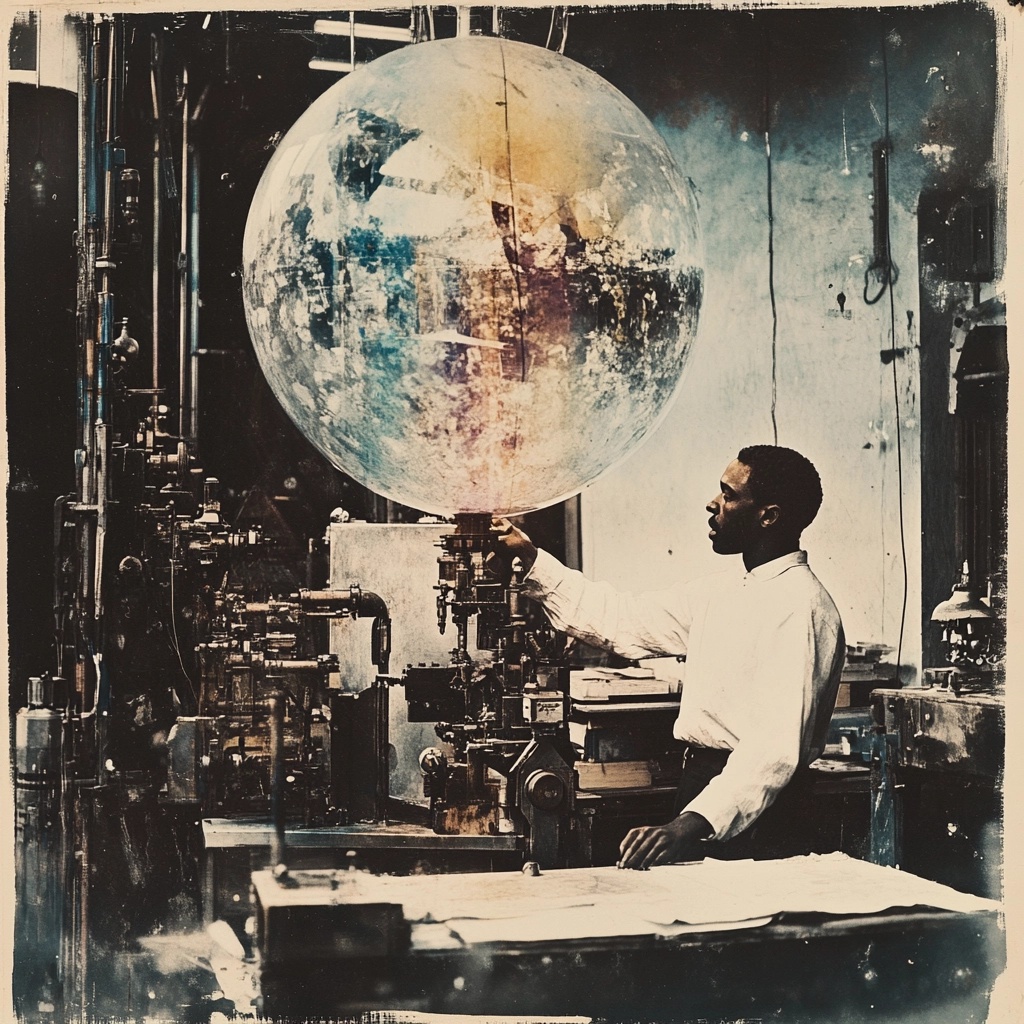

The old man rose and reached up to the gloomy ceiling — we glanced and saw a network of levers and wires and a great bright silent wheel that whirled so steadily it seemed quite still till ever and again its cogs caught a black ball and sent it whirling till it stopped in the faint tinkle of a silvery bell. The old man seized a lever and swung his weight to it — click-click-clank — it said. We heard the slow tremulous sliding of a great mass. “Look,” he said. We looked out the great window and there hanging before it we saw a vast solid crystal globe. I think I have never seen so perfect and beautiful a sphere. It was nearly fifty feet in diameter and seemed at first like a great ball of light, a scintillating captive star glistening in the morning sunlight.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.