BEATRICE THE SIXTEENTH (3)

By:

March 25, 2024

Beatrice the Sixteenth: Being the Personal Narrative of Mary Hatherley, M.B., Explorer and Geographer (1909), by the English feminist, pacifist, and non-binary or transgender lawyer and writer Irene Clyde (born Thomas Baty) introduces us to Armeria, an ambiguous utopia — to which we are introduced initially without any firm indications of its inhabitants’ genders. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize this ground-breaking novel for HILOBROW’s readers.

BEATRICE THE SIXTEENTH: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13.

THE PALACE

In the morning I seriously expostulated with Ilex on the score of the lavish hospitality of which I was the object. My idea had been to raise the trifling sums necessary for simple subsistence, together with enough to hire a guide and a camel or two, by treating cases of ophthalmia and other ailments which yield to European prescriptions after defying the local practitioners. But there did not seem much prospect of putting this scheme into effect. Meanwhile I was handsomely lodged and sumptuously entertained at no cost to myself.

“You are not tired of us?” said Ilex.

And when I said I was not, a brilliant smile made me feel that I could not in fairness pursue the subject.

“My turn on guard ends today,” went on my companion, “and I want to take you to the palace tomorrow myself. The queen is away; still, there will be people there you may care to see.”

“Is the palace itself handsome — finer than this?”

“Oh, decidedly finer. Yes, this is plain, rather. You notice there is a little emptiness about these rooms. The Royal Palace is more ‘lived in.'”

“Athroës told me yesterday,” I said, “that I should find a political crisis in progress. Is it an easy one to understand, and has it an admitted existence?”

“Well” — Ilex looked rather uncomfortable — “Brytas can tell you more about that than I.”

Brytas muttered something about there being really nothing of any consequence in the matter. Some people fancied the general safety was in danger if three ambassadors were seen talking together. There were always rumours, if one listened — and so forth, giving me the strong impression that something of a distinctly unpleasant character was within the range of practical politics.

I saw it was useless to follow up the matter, and when I was left alone with Cydonia (who was busily engaged in drawing up a kind of official report), I contented myself with watching the process, until H had some notion of the characters used. The writing was syllabic — that is, the letters represented syllables, like those of the Japanese. As Cydonia wrote and read the report at the same time, I began to acquire a working knowledge of the hieroglyphics. One great help in making oneself understood was the stately, unhurried rate at which everyone spoke, delivering the sonorous syllables ore rotundo. Otherwise it would not have been easy. The final m, for instance, was universally replaced by n; g was thickened into a harsh guttural like the Gaelic loch. The writing was purely phonetic; every accented syllable was indicated, and every sliding vowel accurately expressed. Occasionally the short vowels were so very short that I have thought it best to omit them in writing proper names.

When I had copied a good many words, I lay back in a chair to study them.

After a while Cydonia, tired of writing, turned from the table, gave a comfortable stretch, and looked hard with both eyes at nothing.

“If you have a minute to spare,” I hinted, “I should be very glad to see the library — if there is such a thing about, that is!”

“By all means. Not a very big one. Come and look!”

We made our way to a room near the top of the building. Outside the warm sun flooded a little stone court with its brightness. Cydonia brought me a seat, and found a shaded corner for it. Then we went into the library and hunted amongst rolls of parchment for something interesting, exactly as if one had been at a seaside resort, and in that want of mental sustenance which is at once sudden and chronic in such circumstances.

“I don’t like to keep you,” I said.

“Well, I must go,” said Cydonia. “Try these.”

I took the four or five lacquered boxes. In each of them lay a set of rolls ready for use. I mounted to my seat, and from it I found that I overlooked the battlements.

There foamed and glittered the tantalising river, so real, so mysterious. I counted the ripples on it, as though it might be possible to detect that they were elaborate make-believes. Beyond it, the wide plain and its belt of verdure. Just visible over the trees, with a start was recognised the Index Maxima. A small band of wayfarers was proceeding across the foreground towards the forest. I turned my eyes away again, and attacked the books.

It was not very easy to read them. During the morning they served mainly as exercises for translation. But later in the day I began to make headway with a volume of geography. It was in the middle that I began it, but I soon saw that it was full, clear, and careful. And I had to recognise that for thousands of miles this extraordinary system of States extended. The only alternative was that the hugest delusion was somehow being played upon me, for no purpose whatever that it was possible to imagine. I took refuge from all perplexities in another talk with Cydonia, who came up with a bunch of grapes for a rest.

“You spoke yesterday about religion,” I said. “What divinity do you worship?”

“The Eternal cannot be mentioned. It is one, and it is many. But generally the people here recognise it under twelve forms — Athené and Artemis and — shall I go through the other ten?”

The system of mythology which was explained to me was very curious. Zeus had evidently dropped out of worship altogether; so had Poseidon, and Hephrestus, and Apollo. Dionysos had become a kind of subordinate demi-god, and had entirely lost — or, perhaps, had never been invested with — the attribute of patronage of the bowl. Hêrê had become identified with one of her minor attributes, and figured in an equally subordinate capacity. It was very strange to hear Cydonia talk; so modern a personage in many respects, and yet absolutely believing in Athene as a living and real power. Not only that, but the innocent, artless stories of the gods on earth were related to me with a certain respect.

“And do you really believe Artemis did that?” I would say.

“She might! It is not my business to inquire. It was a beautiful thing to do; therefore, as she embodies every beauty, she did it.”

“But that is to ignore space and time.”

“What have space and time in common with morals?”

“What have morals in common with beauty?”

“Everything. When Ilex looks most beautiful — which is when you come into the room — has sweetness nothing to do with it?”

“I think,” I said, “Cydonia, your work will be suffering.”

The hint was taken, and I was left alone.

I did not wish my casual stay in Armeria to be the occasion of a complication of this kind.

Until nearly the time for the evening meal I read. Cydonia came for me, bearing no malice, and as the faint flames flickered on the silver chains of the tall, thin candelabra, with a fragrant smell of spices burning in the oil, I learnt that only Brytas would be our companion that evening, Ilex having to wait on an important errand, which I could see gave Brytas some uneasiness.

The meal was a quiet one; and afterwards we had music. Brytas seemed unable to do anything but wander from one tune to another, without five minutes’ rest. Cydonia and I were restless, too, except when the cithara was playing; and we did not talk, except for snatches of comment on the airs. We called in a servant who played remarkably well on the hautbois. But none of us could listen to it. Brytas began to play again, and kept us quiet, until, in the abrupt way which was usual, the music stopped, which we took as a signal to seek our own apartments.

At breakfast Ilex (evidently just come in) and Brytas were both in radiant spirits. No sooner was it over, than the former announced that the expedition to the palace would take place at once. For a second time I traversed those fresh, wonderful streets. A striking feature in the topography of the place was the constant occurrence of broad, clear canals, crossed by innumerable bridges of varying construction, and skirted by gardens; or by the waterfronts of buildings, marble or dark grey stone, as the case might be, but always massive and dignified. Past one of these waterways our road led to the palace.

As we approached it, the vast extent of it grew on one. A good part of it consisted of one story only; but, then, the proportions were so magnificent that it seemed rather a cluster of halls and temples than a mere dwelling. Partly these components of the pile were isolated, partly joined side by side, and partly connected by colonnades, towers, and lower ranges of buildings. The fort-like mass which I had before seen we passed by; farther on the grey stone changed to marble, and a rather heavy portico of colossal size appeared. At the back was a panelled wall of cedar. In its upper part the panels were profusely carved and pierced, and in the lower portion were five lofty entrances, the doors open, and guarded by silent white-robed figures. Ilex walked in, without ceremony, by the central portal. We found ourselves in a large square hall, dimly illuminated, and traversed by a corridor at the back, while a staircase of unpolished wood led, in ample breadth, up one side.

Ilex turned to the right, and entered a comparatively small room, saying:

“I will leave you here while I get my official work done. It will not take many minutes, and in the meantime—”

A page had followed us in, and received instructions to bring Opanthë, who, Ilex assured me, was in the intimate entourage of the queen, and would do the honours of the palace. In a moment, almost, and altogether before I had time to inspect as I should have liked to do the matchless ebony carving with which the walls were enriched, or the curiously wrought metal caskets, with openwork sides, standing in the room, a door opened — the partitions seemed everywhere to be full of doors, leading one could not tell where — and there came in the most beautiful girl I had ever seen. Clad in robes of white silk, fair and regal, she might have been herself the queen of the country. Her beauty did not lie in her expression, which was impassive, but in the uncommon regularity of her features and in her perfect carriage. To complete the picture, she was not very tall, and far from thin. Certainly I had seen no one in English ballrooms who would, on the whole, have been pronounced her equal in the conventional elements of beauty.

She advanced towards me, unaffectedly enough.

“Ilex says you are a stranger here, and to be looked after. Well, I’m very glad it has fallen to me to meet you the first in the palace. Now, what can I show you? Do you like to see jewellery, or statesmen, or architecture?”

“I almost lose myself,” I said. “This place is so enormous and so complicated that I can’t yet grasp the ground-plan of it, nor understand quite who occupy it.”

She tried to explain, but had not proceeded very far when she caught sight of someone passing in the outer hall, and, with a word of apology, got up, and returned in the company of the Grand Steward, Galêsa.

This was an unexpected honour, which I had not bargained for. Galêsa’s cold, contemptuous eyes glanced with something of haughty suspicion round the apartment. Opanthë told him who I was, and I was entirely overwhelmed by the polite grin with which he unexpectedly favoured me. He sat on the divan by us, and showed a flattering interest in my adventures and experiences, over which I took care to throw a discreet veil of mystery, not wishing to be generally accepted as a more or less insane wanderer.

But we had not got very far when Ilex returned, and Galêsa thereupon strode out, brushing down an ivory toy pagoda on the way, and proceeding without taking the least notice.

But Ilex did not remain with us. It was explained that a meeting of officials had been hurriedly arranged, and would make us stay some time longer than we had expected. Meanwhile Opanthe offered to show me parts of the palace. She called to accompany us two of her subordinates, among whom I recognised with pleasure my acquaintance Chloris.

Opanthë shot a sudden gleam from her impassive eye as she noted that Chloris was known to me. The latter, however, welcomed me with cordial freedom, and by no means so stiffly as on our first introduction. I began to feel at home in the vast series of saloons and galleries, enriched with carving and glowing with colour, through whose mazes I was led: halls where stately banners hung over the thrones of the chief of the realm; treasuries of beautiful and rare objects; chambers furnished with silks and tapestry; rooms of state, worthy of a queen, in their ample breadth and magnificent walls and ceilings; arcaded galleries and carved pillars; and everywhere the royal cognisance of a golden sphinx, uniting the whole into compact loveliness. There were rooms for the principal personages among the queen’s relations, for the officers of state, and for the band of attendants who here, as elsewhere, seemed to be indispensable satellites of royalty, from the menials to the minstrels and Court ladies.

Among them was numbered Chloris, and I asked her how it was that she was not at the palace when Cydonia and I had met her.

“I am a good deal at home,” she explained. “Opanthe and I have a suite of rooms here — you must come and see them — and Etela: she has just been introduced to you, you know — the tall girl in green. But I find it’s dull sometimes, and I like to get back and see my little cats, and feed my crocodile, and talk to the people at home. To tell you the truth, they are rather a stupid lot here! They think so much about dress, and politics, and promotion, I get tired of them.”

A funny combination, I thought — dress, and politics, and Court gossip — and not inconceivably a fatiguing one.

“Besides,” pursued Chloris, “Etela is so very — well, feeble; and as for Opanthë, she is no good to me. Then the rest, living apart from us as they do — you see, they have their own private interests, which makes one rather isolated. Of course, I am constantly meeting them; but it is different when one’s own particular rooms are all together, isn’t it? We three are just a little bit of a clique apart. Very nice if we were all charming. None of us are!”

Opanthë, with the dignitary who accompanied her, stopped, and slowly turned towards us.

“If you are not tired,” she said, “I will take you across to the Slave Emporium. It is part of the palace, because the distribution of slaves is so vital a matter to the kingdom’s interests.”

This proposal excited Chloris immensely. Plainly it was not an everyday opportunity.

“Oh, Opanthë! Are we really going to see that? Think of it! I am in luck’s way! May I —”

But she broke off, as Opanthë led on without vouchsafing any attention to her outburst. She consoled herself by explaining to me that the barbarian children destined to become slaves were brought, on attaining a certain age, to the palace, where they were lodged for a longer or shorter time, until disposed of to suitable applicants. It all seemed a very strange system. Chloris declared that no price was paid for the slaves; and yet it seemed that the owners had more or less power of selection. But a rather remarkable thing was that, during their custody at the palace, no one except their immediate guardians and intending allottees was admitted to see them. There was no actual bar, but it was considered improper, and no facilities for it were given.

It was, in fact, for a palace official to visit the slave quarters much as it would be for a Belgravian lady to invade the kitchen. Consequently, Chloris, with a youthful love of mysteries, was full of lively anticipation.

As Opanthë unlocked a heavy old timbered door, the girl held her breath with suppressed interest, and positively shook. But to me, who had no associations of mysterious concealment connected with the place, it was not impressive, however interesting. A tall and venerable person wearing a scarlet headdress came up to us at once, and demanded what we wanted.

“This lady is a foreigner, and the queen wishes her to inspect all that there is of interest in the palace,” answered Opanthë. “In her country, Zenoris, there are no slaves; and, naturally, this is of the greatest importance for her to see, that she may not go home with wrong impressions about us. I hope you have everything in very good condition.”

“It’s not usual for anyone to come here unless her majesty herself is with them,” remarked the custodian. “But if your ladyship assures me that all is in order, of course I can’t say anything.”

“You may be quite easy,” said Opanthë carelessly and haughtily.

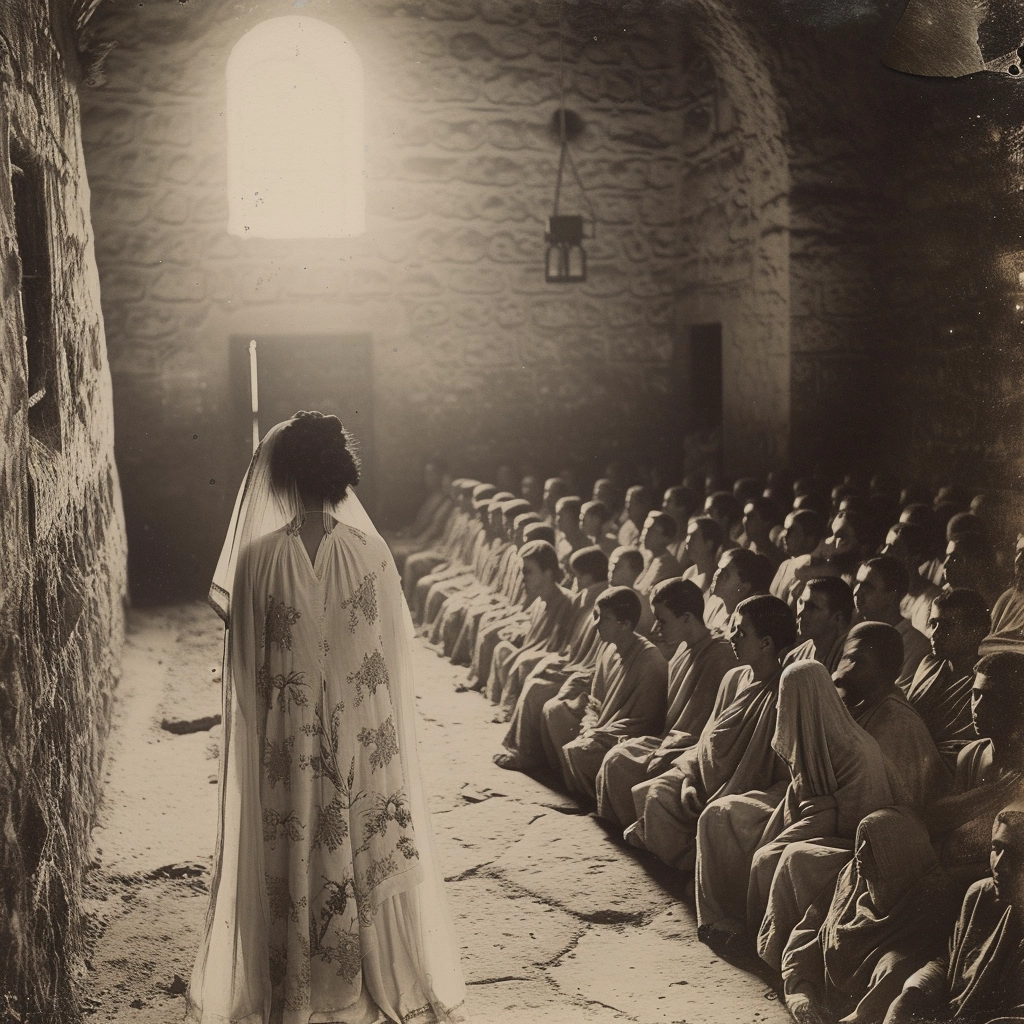

We had crossed a wide terraced garden, and traversed a stone corridor to get to the place where we now were, which was a very quiet grassy enclosure, with high walls behind us, and a low building in front, at the side of which was an orchard. Nobody but two or three of the scarlet-capped officials was visible: they were seemingly pottering about, attending in a desultory fashion to the flowers. We had to enter the building to see the slaves. Apparently, no restriction was put upon them or their movements. Chloris viewed them and their abode with an interest which she did not disguise, and I began to consider that the sentiment which excluded palace officials from the precincts was not misplaced. What pleased me was the sympathetic and kindly way in which Opanthë moved amongst those unfortunate creatures. As I watched her, it seemed like a vision of Eurydice in Hades, as I had seen it on the stage in Glück’s Orpheus. And they seemed to appreciate and reciprocate her cordiality towards them. The faces of most of them grew brighter at her approach, as though some spell united them in a real and an unequal friendship. Otherwise it was a melancholy spectacle. Forty human beings, of like capacities with ourselves, were here secluded in readiness to be sold off to a life of servitude and contempt. The vaulted stone chamber which was their principal room, spacious and lofty as it was, seemed like a prison to me; and their general attitude was, so far as one could make out, one of dull apathy. There were no jokes, no songs, no knots of lively gossipers. One could not say that they appeared unhappy or sunk in despondent wretchedness. But there seemed to be a depressed spiritlessness about them, whether due to the barrack-like system of their education or to the uncertainty of their future portion I could not judge. Perhaps it might be owing to both causes. So far as I could see they were well treated. But I thought Etela, who accompanied us, betrayed some uneasiness when I began to talk to some of them, so I desisted.

From the central hall great arches in the stone wall led on each side to smaller rooms, and at the farther end came a kitchen. Crossing this, we reached a chamber formed by the double gates of the street entrance. The porters admitted us through the inner pair, and carefully locked them before opening the outer ones. Opanthë then took me into a handsome set of rooms opening off this chamber, which she observed were used for the purpose of giving applicants for slaves an opportunity of seeing those available for disposal. Passing out into the free air of the street, we entered the palace by a small marble doorway and a little flight of stairs, and found ourselves, after some careful piloting through the intricacies of the buildings, in the hall I originally entered.

We went into a different reception room, where a dozen or so of the palace ladies were found. The usual quaint and polite greetings were gone through; coffee, sweets, and so on — though it was not midday — were sent for; and I was soon on excellent terms with the unsophisticated, pleasant company, who hardly seemed to me to deserve the strictures of Chloris. Perhaps I had expected them to be particularly vapid and narrow-minded, and was unprepared for the fresh candour which they certainly showed me. They neither quitted their own occupations in embarrassed silence nor ignored the presence of a visitor, but went on naturally with their work or talk, leaving it to those nearest me to do what entertaining was necessary.

As I sat on a low seat beside Opanthë, I talked to her and a fair, low-voiced friend of hers, whilst in reality my attention was taken up by a little group near us. The centre of this was a plain-looking cousin of the queen’s (as I afterwards found) — the Princess Iôtris — whose grey cloth dress contrasted oddly with the delicate shimmering robes of most of the others.

It was long weeks — and it seemed long years — since I had heard the sound of irrepressible, civilised laughter, and the spontaneous explosions of merriment which reached me from the little group attracted my attention in spite of myself.

It was not that she said anything so very amusing, but her playful and friendly manner infused a spirit of readiness to be amused into her hearer, of which they took full advantage. She did not laugh much herself, though she smiled continually. To say that she was the centre of the group was to use an Irishism, for she actually stood, erect and firmly set, facing her companions, and rallying them in turn, while they retorted in kind.

“My friend Valthis, it is no earthly use trying to persuade me; you cannot get a genuine work of art painted nowadays — not like Lychthis, or Vitra, or Œnoné!”

“It may be no earthly use my trying to persuade you; but you can get as good artists, nevertheless — plenty of them!”

“Plenty! Well, we are well off! Did Lychthis, and Vitra, and Œnoné all live at the same time?”

“Surely,” said another voice, “Thekla is worth comparing with any of them?”

“Ah! Thekla!” answered the Princess. “But we can’t go to Thekla and say — ‘Paint me a picture — here are five hundred crowns.'”

The whole assembly burst into tumultuous laughter. But the lady addressed as Valthis took up the thread of the argument again.

“Could you have said that to Œnoné?”

“No, because fifty crowns would have been enough for her, in her days. Five hundred crowns for a picture would have seemed frantic. She would simply have laughed at you as a lunatic,” responded the Princess quickly.

“But I always understood,” went on Valthis, “that Œnoné worked for the Governor of Thorosa, and refused to do anything for anybody else.”

“Your historical knowledge is correct, my child. But my point is, that one couldn’t engage an Œnoné now, on those or any terms, even if one were Governor of Thorosa.”

“And a good thing too,” struck in a fourth. “Free trade in Art! That’s my idea. Why should an artist be monopolised by one respectable Governor?”

“See what your idea has brought us to,” observed the Princess. “Not an artist left in the place! Except Thekla, and that’s as good as nobody. For she will only paint to please herself.”

“Don’t say ‘not an artist,'” remonstrated a young person, who was, in the calm obscurity of the floor, at that moment engaged in washing in some colour into a parchment scroll. “I’ll take the five hundred crowns — or the fifty — with pleasure. And Irmathé, you’re wrong if you implied that the Governor who employed Enoné was respectable. He wasn’t — not if raiding your neighbours is improper.”

“I accept the correction. And I presume it is the purple of Cassius that you put into your painting that brings the price up?”

To cheap remarks of this nature the artist soul pays no attention and the painter simply addressed some candid and helpful remarks to her brush which had got stiff.

“When a painter worked for a patron —” commenced the Princess instructively.

“The Lady Thekla is present,’ was announced by a herald. I looked up curiously. The Princess bit her lip, her eyes twinkling. The girl who was painting rolled up her parchment coolly and silently.

Thekla was small and short, and bent forward. She had large, restless eyes, that roamed incessantly from one point to another, and, for the rest, had pale, thin features — almost European-looking. Her movements suggested the rapid dives of a waterbird from sedge to sedge. She was evidently a frequent visitor, if not a member of the palace company, for no formal salutations were given. The Princess engaged her in conversation, and good-naturedly introduced her to me after some minutes.

“I understand you are a great painter,” I said to her, and I was half sorry. Her face flushed, her fingers crushed each other, and she coughed, and scarcely could speak.

“Some people like my things. I never can do my best — it is very difficult.” Her tone was abjectly apologetic. Had I made a frightful mistake? I remembered, with a gust of annoyance, the outburst of laughter with which Thekla’s name had just been greeted. Was all they had said sarcastic, perhaps?

It was safest to go on. Evidently she took herself seriously.

“Do you paint the figure or landscape?” I asked.

Thekla recovered herself a little.

“Oh, nobody ever paints the figure,” she explained. “You can only, at the best, make a kind of caricature of it. Yes, I paint scenery and trees, and I am very fond of painting water. People say I can paint water — I don’t know, myself. But I think there is nothing so lovely as splashing streams, coming down between green leaves — all kinds of green leaves! I like to fix them. At least, I would if I could. Do you care for such things? If you do, I will show you what I mean.”

She opened a case that was by her side, and showed me a coloured drawing. I do not pretend to have the least critical taste in Art, but this struck me as Japanese work has often struck me, though it was more elaborate and not so dashing as Japanese paintings. It had a vividness and directness which seemed absent from our Western galleries — a pith and point which evidenced a thorough love for and sympathy with Nature. Every crystal drop seemed to quiver with life.

She saw I was pleased, and let me see another.

It was a brown, arid mountainside. The jagged peak rose clear and distinct into the blue sky, without a cloud or a waft of mist. But the torrent’s source was here, and its trickling stream was gathering out of the marshy pools, its infant course marked by the change in the character of the vegetation. There was not a solitary bird or any living creature in the landscape. Its solemn beauty and its suggestiveness of the silent forces at the root of things were produced by the simplest means, though the dexterity of hand with which the painting was done was remarkable. I am not an art critic. Nothing that pleased me more had ever come to my notice, nevertheless.

I admired it duly, to Thekla’s evident relief. I should have thought her modesty affected, only that it would, in that case, have been so violently overdone as to be ridiculous.

“Come to my house the day after tomorrow,” she said. “You will meet better painters than I, a great deal, there.”

People were rising, and Opanthë invited me warmly to accompany the party to the midday meal.

“Now that Thekla is here,” she said, “we will have a regular feast. Come on, both of you!”

Thekla and I got separated as we entered the banqueting hall. There were many more officials of various kinds there, but the younger artist — she of the floor — took me under her wing, and made me sit beside her. At a cross-table, slightly raised, sat the Princess Iôtris, among a galaxy of other ladies of the blood-royal and high officials, — most of them much more splendidly costumed; many not so pleasant-looking. Between the two long tables the service was carried on. Opposite the daïs a high platform served as a vantage-ground for a band of harps and clarinets. My neighbour was a caustic conversationalist, and Opanthë was not far away.

“Will Ilex be able to find me if the meeting should break up now?” I asked the latter. She satisfied me on this point, and turned to speak to the nearest person to her on the daïs. To my vexation, it was the Grand Steward, Galêsa, and between him and Opanthë sat two sullen-browed men, who were evidently well acquainted with him.

“Kisêna,” said one of them to my artist friend, “have you washed the colour off your face yet?” He did not wait for a reply, and received none, but guffawed insolently. I felt intensely uncomfortable. Kisêna did not in the least. She coolly helped herself to salt, and asked me in a perfectly unmoved voice what I thought of the state of public affairs.

“I have arrived so recently,” I said, “I know nothing about them.”

“Oh!” said Kisêna. “Then I must tell you things are pretty critical.”

“In what way?”

“Mainly with regard to Uras. The long and short of it is they want a complaisant monarch here, who will do as they tell her. Beatrice, of course, won’t, and there are incessant quarrels. They haven’t much hope of overcoming us, but they do flatter themselves they can change the dynasty.”

“Ah!” I said, “and who is their candidate?”

Here I caught sight of Opanthë’s face, as a servant lifted away a huge silver drinking bowl from between us. The eager attention which she seemed to be giving to our commonplace conversation half frightened me. She was listening with tense muscles and strained eyes. I pretended not to see her, and the next time I looked she had resumed her attitude of impassive hauteur.

Kisêna did not know of any definite person being suggested as the Urassic candidate for the crown. But as we left the hall, she proceeded to say in a lower voice that the most serious feature of the situation was that strange ferments seemed to be developing among the slaves — a thing unheard of, as she explained to me, in that or any other country.

I told her I was surprised.

“Are the slaves so reconciled to their lot,” I said, “as never to make an attempt for freedom?”

“People have to be pretty wretched,” she answered, “before they revolt. And I do not think our slaves are badly treated, nor those of Cranthé, or Agdalis, or Kytôna. Naturally, they have their grievances.”

Suddenly the columned portico where we stood grew warmer and brighter. Ilex was at my side, and carried me off to a pretty isolated house, not many streets away, where the fortunate owner had succeeded in producing a chrysanthemum of what I was told was an entirely new tint. The plant which had so obligingly taken the trouble to allow itself to come into existence was enthroned like an imperial favourite among a wilderness of mosses and ferns, a high folding screen forming a background. Open house seemed to be kept for its admiring worshippers, and the scene was laughably like some odd shrine, resorted to by devotees, whose hushed enthusiasm might show itself only in murmured exclamations of ecstasy. The smoking incense, whose vapour rose from jars set before the screen, completed the illusion. We did not stay long here. Ilex returned with me to the Warder’s Palace, and I found myself once more in the little room where my first meal in Armeria had been taken. It brought back a flood of recollections, and seemed to throw me back again to my first evening in the city. The old restless desire returned to know what was the real explanation of the extraordinary experience which had befallen me.

Brytas and Ilex did their utmost to rouse me from the uncomfortable state which they could see I was in. The latter talked of the suite of rooms that was being prepared for me at the family residence, three miles away, and was very anxious that I should accept the offer of it.

“Much pleasanter than having you here! Besides, I have made all the arrangements, and we expect you.”

“I can’t choose!” I said. “I am endlessly indebted to you, however it is settled. And I must say it would be very interesting to me, as a foreigner, to be admitted to a private house here. Still, it does seem an infliction on your family.”

“If you can’t invite a stranger there, what is a house good for?” sagely reflected my host.

“May I ask who compose your household?” I inquired, rather languidly, and by way of being civil, for at the moment I felt, in spite of all the kindness I received, as dull as the proverbial ditchwater — in cloudy weather, you may add.

“Well, there is Parisôn —”

“Is that a lady?”

“Yes! — Cat, did you think?”

“No; but I thought it might have been a man’s name.”

“So it is. Where is the difference? I am afraid I don’t quite make myself understood —”

This comes, I said to myself, of thinking one knows a language when one hasn’t been taught it properly. Evidently kyné and anra both mean “person” in this tongue. I tried another line.

“It is my ignorance of the language that is at fault,” I remarked. “I don’t know the right pair of words. Do you say femina and vir? Or mulier, homo?”

“Homo is a word we have,” interposed Brytas. “It is the same thing as kynë or anra.”

“Not femina — nias — vir — wir — bir — mir?”

They looked blank.

“No, none of them. Mara — ‘the sea’ (chals) — that can’t be what you mean?”

“You said bir,” said Ilex. “We have persona — that can’t be it, can it?”

Philology could not go that length.

“How do you distinguish,” I observed, in despair, “between the people who — who fight and wear whiskers and moustaches?”

But it suddenly occurred to me that none of them did wear them.

My companions, evidently thinking I had got beyond my depth in some recondite speculation, charitably — as people will do in such circumstances — began to talk very seriously about something else. I thought, and thought. Finally, I broke in upon their gentle ripple of conversation.

“Do you mean to say, then, that you do not recognise any division of people into two classes?”

“Free and slave, do you mean?” said Brytas hopelessly.

“No; in every rank, in every class. Two complementary divisions, each finding its perfection in the other.”

“I never heard of such a thing,” Brytas answered coolly.

“Nor I,” returned Ilex. After a pause, the former observed: “For my part, I cannot see how perfection is to be attained, except in one’s own spirit.”

Upon which followed an awkward silence, during which I candidly confess I was incapable of speech.

“Well,” Ilex said, with sudden brightness, “we must move off now; we have an hour’s walk before us!”

It had grown dark; the streets twinkled with tiny coloured lights, and there shone fitful gleams of lamps through the latticed casements. You could not see the trees, but only a kind of feathery motion in the sky, where their fronds waved before the light airs of the night. Even the stars had veiled the splendour of their tormenting brilliance. And it was pleasant to forget them, and to lean one’s perplexed head on Ilex’s shoulder as the arm passed round one’s waist invited one. He or she, it was consolatory, all the same!

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | & many others.