Roadworthy Jazz

By:

December 21, 2011

This article was first published in Hermenaut #15 (Summer 1999). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

Last year I finally got a driver’s license. One night a few weeks later, someone talked me into going with him up to Ho-Chunk, the closest Indian casino to Madison, Wisconsin — about 50 miles north on the interstate. About a half-mile before the place, a sudden torrential rain occurred. Soon I couldn’t tell what side of the road I was driving on. I felt sure that we were almost at the casino, though. Fortunately, I was right: Ahead of me and on the left, two hundred lights shot through the rain, saying, Here is money and excitement! And there was safety, too. It reminded me of the Bates Motel sign appearing to Janet Leigh in Psycho.

If you have a car you do these things, you go to these places filled with money and excitement. Cars exist in a universe of money and they’re drawn to centers of money, taking their drivers with them. You gamble more when you drive a car. You expose yourself more to chance, to the interplay of forces not wholly predictable. I can’t die yet, I didn’t use up all my complimentary drink coupons from the Cooler.

Yet you have more control, too — that is, you have at least to claim to be in control. The driver of a car makes a larger claim than a pedestrian or a passenger does, has a larger sphere of influence, through which countless other enlarged spheres whirl over the course of a trip. As this sphere of influence widens, the sphere of time contracts. The faster you go, the smaller the time intervals you have to deal with. So, in gambling, time is experienced as discrete events more compressed than are events in normal life. I don’t play slot machines, but I can see the attraction; it’s like an ultimate stage of driving, getting in front of the handle of one of those things and pulling it. It’s a version of trance. Time, real time, the great time in which these events occur, loses reality. The artificial world of the casino is designed to replace this time with an even more impersonal totalization. Each event involves you in a micro-judgment that tends toward the automatic.

Let’s leave the Ho-Chunk, where you can’t even get a drink — an alcoholic drink, they give you cokes and you’re wired pretty soon, well like I say you lose track of time but let’s suppose it was two hours. You’re past the edge of exhaustion, playing blackjack, you lost almost all the way down to the limit you set yourself for tonight, then you won almost all of it back, but you sense you’re starting to lose again, so you quit twenty dollars behind. Time to head back, to re-enter time and the world and be surprised again by the stark unfamiliar Midwestern night, to get back in the car, to brave the ordeal of the interstate. Time to face the really important question: what to listen to?

Someone once asked me to make a jazz tape to listen to in the car. At that time my experience in cars was mainly as a passenger, so in making the tape I chose music that I thought would be fun to listen to while someone else was driving. I had little direct intuition of how music can promote or block the astute semiconsciousness ideally conducive to driving. I didn’t know then what I know now: that music and driving are linked as totally, as fatally, as driving and money. If I give up something of myself, of my individuality, in the banality of driving, I must get something back from the heightened loss of self provided by music. Music completes in terms of pleasure the ecstatic flattening of the driver into invisibility and microtemporality by allowing the flattening to be experienced as an inflation.

With these considerations in mind, herewith I present the ten best jazz records for driving, in reverse order of roadworthiness:

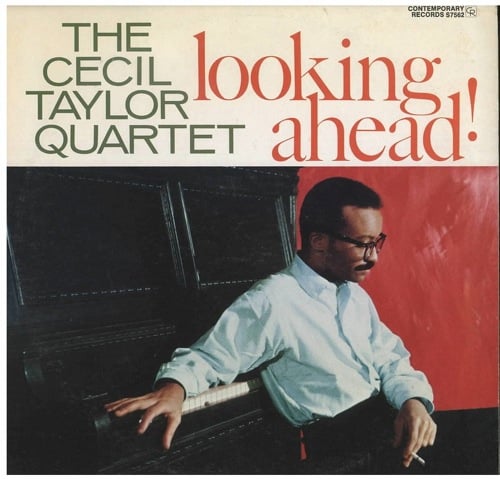

10. Cecil Taylor, Looking Ahead. Some might question this choice. Ideally, music listened to while driving would not distract you from the road by requiring you to pay too much attention to it, and what would a Cecil Taylor record be without paying attention? Well it might be something like Looking Ahead. Cited with surprising frequency by people as their favorite CT album, Looking Ahead is from the period when Cecil was still doing stuff based on chord changes. On this record he does a song based on the chords of “Take the A Train” (it lasts 9 minutes and 5 seconds, the approximate driving distance from Boston to Braintree, Massachusetts). Another thing that helps make the record accessible is the vibes player, Earl Griffith. By the way, “looking ahead” is good advice for any driver, except arguably when you are in reverse, in which case you may wish to adjust your volume.

9. Lee Konitz Meets Jimmy Giuffre. Like they said about New York, this record’s all right if you like saxophones. Pick an itinerary that won’t involve any complex maneuvers, so that you can devote as much attention as possible to trying to memorize Warne Marsh’s solo on “When Your Lover Has Gone.”

8. Duke Ellington, Anatomy of a Murder. This makes most sense as driving music if you’ve seen the movie, which takes place mainly in a courtroom but has a few car scenes that stand out because of camera movement, lighting, and actingŠ and because of the music-that extraordinary, mysterious music that’s so American, somehow in an even more essential way than jazz in general (an American art form as is so often said) is. Why? Maybe because of the movie, which itself is so American, so Midwestern… even though it was directed by an Austrian.

7. Paul Desmond, Bossa Antigua. Desmond said he wanted his alto sax to sound like a dry martini. This either didn’t work or worked too well for guitarist Eddie Condon, who said of him unkindly, “He sounds like a female alcoholic.” Let’s remember that alcoholism is a debilitating disease. Condon perhaps was shocked by the flatness of Desmond, the lack of joy that becomes overpowering, a lack of joy and a lack of despair. All he does is go on. His art suggests an exact equivalence between the phrase he plays and the breath he has for the phrase, so you feel: That’s all the air there was; this music seems to be merely of the air, not straining it, merely equaling it, giving back the same amount it takes. There’s an inevitability about Desmond’s passage through time and space: It leaves nothing behind it changed. This effect, needless to say, can be supremely comforting for the driver, who needs the confidence that time and space passed through will bear no imprint of the vehicle. Therefore, although drinking and driving is not to be advocated, it’s okay to drive while listening to Bossa Antigua.

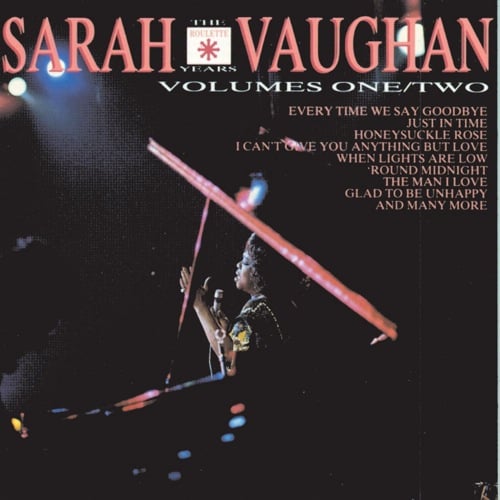

6. Sarah Vaughan, The Roulette Years. Trying to explain Sarah Vaughan to people is futile, it’s hopeless, and it’s so unnecessary when, as usual, the proof is in the tiramisu. Not merely a great musical stylist, Sarah Vaughan is also a supremely enjoyable driving companion. How she negotiates intervals (e.g., in the last chorus of “Have You Met Miss Jones?” and the bridge of “Lover Man”), how she invents varyingly elaborate and risky disciplines for herself, goes through them, and comes out triumphantly at the other end… these things themselves are driving lessons, although mere expertise would do well to imitate such mastery cautiously.

5. John Patton, Boogaloo. This is a tantalizingly progressive-hinting Blue Note soul-funk organ-combo session from 1968 (unreleased until 1995). Everything about this record speaks brilliance, energy, and disencumberment. The musicians constantly delight themselves by throwing sly, slithery tensions at each other and it’s tremendously groovy how they ride the simple modal structures and intense rhythms. I’m not sure why the somewhat unusual combination of organ and trumpet is often held to be a recipe for failure. On Boogaloo, Patton and trumpeter Vincent McEwan prove that the combination is surefire hot-dog success as far as driving is concerned. I’ll go out on a limb and suggest that it might in fact be the ideal driving combination. Why? Because it has both duress (the organ) and flight (the trumpet), the chthonic (the o.) and the Euclidean (the t.). Another good example is Don Patterson’s excellent Boppin’ and Burnin’ with Howard McGhee. There’s also Lou Donaldson’s Fried Buzzard with Bill Hardman and Billy Gardner; Larry Young did a record with Lee Morgan; Ruby Braff had a thing with Dick Hyman on pipe (!) organ… the list goes on, but not for very long.

4. Four is up for grabs: You can write in your own candidiasis! The only rule is that the name of the album has to contain the name of the artist. Here are some suggestions: Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section, Stan Getz Plays, Patty Waters Sings. You don’t have any ideas? Call it a three-way tie. Speaking of which, it’s my considered opinion that jazz trios are great indoors and in restaurants but all too often let you down on the road. Maybe speakers have a lot to do with it, because a trio record is diminished in power by more than a third if you can’t hear the bass, and once you cross the murky frontier between adequate and inadequate sound systems the bass is the first to go. So before you decide to bring your Herbie Nichols records on your next road trip, make sure your system is ready for them.

3. Miles Davis, Panthalassa. “Reconstruction and mix translation by Bill Laswell.” If you like to be in a trance while driving, or if you are trying to put someone else in a trance, or get them to shut up, you may find this recent release especially valuable.

2. Thad Jones and Pepper Adams, Mean What You Say. This one I picked up for $2.99 in a department store where I was shopping for dill-flavored potato chips. You can still find things in this country if you don’t know where to look. By any rate of conversion between notes and pennies this is one of the best values in jazz history. You’ll want to listen over and over to the supple, understated arrangements of the catchy original tunes (plus Burt Bacharach’s always welcome “Wives and Lovers”). What a polished album! The combination of Jones (trumpet) and Adams (has been considered the best of all baritone saxophonists) has an unusual mellowness. Truly a fun record, except briefly when they try to be fun by doing “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” and even that becomes fun once you make it past the head (it’s kind of like paying a toll).

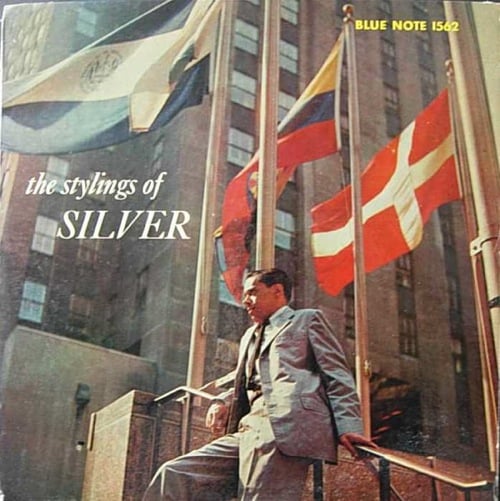

1. Horace Silver, The Stylings of Silver and Further Explorations (tie). Silver is the great humanist of jazz, and since valuing human life is good to do while driving it may be desirable to bring Horace along as your guide. These are possibly his best records; they’ve got to be among his four or five best. Each song is a gem of lyricism and filth. The music expresses fierce pride and the complexity, strain, and pleasures of city life. You might prefer to do your driving out in the country, but whatever your environment, the up-frontness with which Silver thematizes, invariably, the dialectic of tension and relaxation makes him the perfect driving accompaniment. (Note on the tie: I prefer The Stylings of Silver but it didn’t seem fair to have an out-of-print record as Number One so I tied it with one that’s in print, Further Explorations; at least it was when I last looked.)

(Totally against the rules of top-ten lists: any Booker Ervin record may be substituted for any record listed. Also, one important warning: Bob Graettinger’s City of Glass is unsafe to listen to at any speed. Is it even jazz?)