Fitting Shoes (6)

By:

September 9, 2010

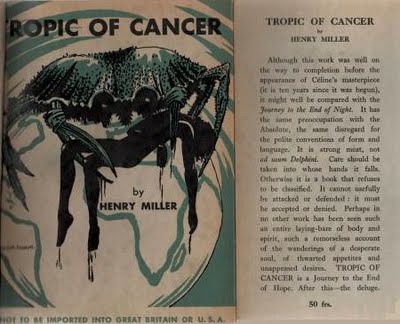

“[Moldorf] falls on [Fanny’s] lap and lies there quivering like a toothache. He is all warm now and helpless. His belly glistens like a patent-leather shoe.” — Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer (1934).

In this passage, Henry, the narrator of Miller’s quasi-autobiographical first novel, is fantasizing about how Moldorf, one of several American expats whom he’s met in Paris’s bohemian demimonde, might behave in the company of Fanny (Moldorf’s wife, living in the USA) — whom Henry imagines as a kind of frumpy, motherly dominatrix android. The patent-leather shoe simile suggests that Moldorf is swarthy-skinned, and in several other passages Henry takes pains to describe him, savagely, as a dwarfish, Asiatic-looking Jew with “thyroid eyes” and “Michelin lips.” Yet the patent-leather shoe simile does more than signal Henry’s reflexive anti-Semitism — it’s a symbolic expression of the author’s life-long ambivalence about success.

As I once remarked in The Idler, though Miller had long aspired to be a renowned man of letters, he didn’t start writing until he was 39 — in Paris, where to be broke wasn’t a humiliation. Before that, he’d worked at Western Union, and loafed, for years.

“I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive,” exults page one of Cancer, which is — among other things — an important idler’s manifesto. “Do you know why I called my first book Tropic of Cancer?” Miller wrote in a letter to a friend. “It was because to me cancer symbolizes the disease of civilization, the endpoint of the wrong path, the necessity to change course radically, to start completely over from scratch.”

What’s Miller’s beef with 1930s-era western civilization? Wage slavery. According to Cancer’s narrator: “We have become so adjusted that, if tomorrow we were ordered to walk on our hands, we would do so without the slightest protest. Provided of course, that … we touched our pay regularly. Otherwise nothing matters… We have become coolies, white-collar coolies, silenced by a handful of rice each day.”

To Miller, the patent-leather shoe represents (aristocratic) freedom from wage slavery. Moldorf, from whom Henry scrounges meals and pin money, doesn’t need to work. Elsewhere in the novel, musing that he doesn’t like seeing the aristocratic Frenchman type wearing bourgeois athletic garb, Henry issues a diktat: “He should wear twinkling patent-leather boots [emphasis added] and in the breast pocket of his sack coat there should be a white handkerchief protruding about three-quarters of an inch above the vent.”

However! Although Miller and Cancer’s narrator both abhor wage slavery, neither the real nor the fictional Henry aspire to be aristocratic men of leisure. Though something of a swell, Moldorf doesn’t cut an impressive figure in Cancer: “He has fermented so long now that he is amorphous.” Though for Aristotle, leisure is a god-like mode of existence, Miller recognizes (much like his somewhat younger contemporaries, T.W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer) that leisure has been perverted by a capitalist social order. In his 1953 novel Plexus, Miller would later write: “We know not how to escape the tyranny of the convenient monsters we have created. We delude ourselves into believing that, by means of them, we shall one day enjoy leisure and bliss, but all we accomplish, to be truthful, is to create more work for ourselves, more distress, more enmity, more sickness, more death.”

Such leisure doesn’t make man godly; instead, it gives him delusions of godlike grandeur: “I am trying ineffectually to approach Moldorf. It is like trying to approach God, for Moldorf is God — he has never been anything else.” The god to which Henry refers is Mammon. Miller exegete Karl Orend has argued that the character of Moldorf was inspired by Joseph Millard Osman, a wealthy American student at the Sorbonne, who hired Miller to ghost-write an academic treatise on the treatment of infirm children in New York — and who introduced Miller to Michael Fraenkel and Walter Lowenfels, on whom Cancer’s other important male characters are based. But I suspect he’s an invented figure, a symbol of misspent leisure, which like wage slavery can wreak havoc on a person’s well-being.

Patent-leather isn’t an inherently superior form of leather: it’s leather coated (originally, in the early 19th century) with layers of linseed oil–based lacquer. By Miller’s time, the development of synthetic resins had made the mass production of patent-leather shoes possible. Mammon, in the form of His avatar Moldorf, Miller would have us understand, is nothing but a patent-leather shoe: an idol whose shining surface is factory-made… and whose feet are clay.

An occasional series seeking to determine the make and model of fictional footwear.