Artificial Enlightenment

By:

July 14, 2010

Until the 18th century, night was an impenetrable abyss. Tallow candles, made of rendered animal fat, barely lightened the darkness. The workday was tied to the sun; once you could no longer see your work, labor stopped. Then tallow candles began to be replaced by whale spermaceti candles, which were twice as brilliant, and by lamps that burned cheap and abundant whale oil. Small wonder that this era was later dubbed the Age of Enlightenment.

[This review of Brilliant: The Evolution of Artificial Light (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), by Jane Brox, appeared July 11 in The Washington Post Book World.]

Robert Louis Stevenson likened gaslight, which by the 1820s was supplied to London via several hundred miles of underground mains, to the work of Prometheus. A few decades later, around the time that Russia’s Paul Jablochkoff was making major improvements to the arc lamp — the first electric light — Ralph Waldo Emerson extolled electric lights for banishing the shadows created by “the flame of oil, which contented you before.” Artificial light, it seemed, was progress made visible.

But, Jane Brox asks, at what cost? Though she celebrates human ingenuity and technical advances in “Brilliant,” her history of artificial light, Brox also presents damning evidence that in our millennia-long quest for ever more and brighter light, we’ve despoiled the natural world, abandoned our self-sufficiency and trained ourselves to sleep and dream less while working more. It’s time, Brox urges, to “think rationally about light and what it means to us.” Yes, the history of artificial light has its dark side, for those who aren’t too dazzled to detect it.

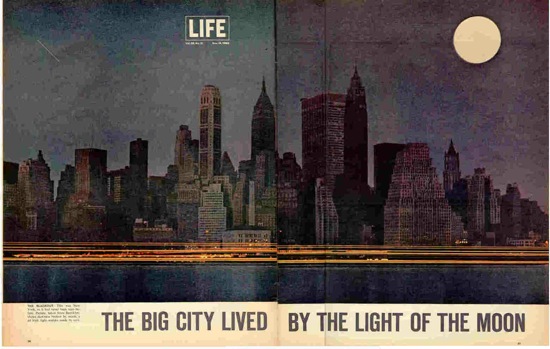

Unlike the compact fluorescent light bulb, about which the author rhapsodizes at one point, “Brilliant” isn’t very efficient. For example, it’s concerned at least as much with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Northeast Blackout of 1965 as it is with what we might call the dialectic of artificial enlightenment. Yet like Edison’s incandescent bulb, which has become the cartoonist’s symbol of bright ideas, Brox’s history is warm and illuminating.

What artificial light has signified to us, according to Brox’s analysis, is the Enlightenment’s promise of liberty and equality. But in reality, the wealthy and powerful have always acquired new kinds of light first and enjoyed a disproportionate share of their splendor. The advent of new lighting in the 19th century, Brox notes, “stratified society and intensified the separateness of countryside and city, household and industry.” As late as 1906, when electricity was not yet considered essential for everyone, electric lighting was available only to businesses, manufacturers and wealthy homeowners. Until the New Deal, everyone else was consigned to darkness.

But perhaps, Brox argues, that wasn’t such a bad thing. Before the advances in lamp technology, the nights were long, and sleep was divided by one or more intervals of semiconscious wakefulness when men and women shrouded in gloom might talk, make love, pray, reflect, even visit others. Sounds delightful, doesn’t it?

Alas, thanks to improvements in artificial lighting, free-running sleep long ago went the way of handlooms. Working hours, meanwhile, have grown longer. The God of Utility, in Baudelaire’s pejorative phrase, demanded brighter illumination, and he received it. Gas lighting was first embraced by factories; a century later, Edison’s light bulb helped establish the three-shift day and the final erasure of natural time in the workplace.

If illumination-disadvantaged people were out of sight and out of mind, so too were the negative effects of artificial lighting on the natural world. In the early 19th century, the demand for whale oil led to the near-extinction of sperm whales. Gaslight, a byproduct of the distillation of bituminous coal into coke, required dangerous mining. Kerosene produced from petroleum encouraged oil drilling, the costs of which we’re still trying to calculate in lost troops abroad and ruined habitat at home.

Part of the allure of electric lighting, Brox recounts, was its supposed cleanliness: “All the attendant work and grime of production existed somewhere out of sight.” Yet, until the energy crisis of the early 1970s, few realized how essential coal mining and oil drilling had become to the energy grids of industrialized countries.

Exploitation of fossil fuels won’t be possible forever, yet visions of a “smart grid” and organic light-emitting diodes won’t fix our fundamental energy problems. Why? Because the more modern we’ve become, the more we’ve taken our lighting and its power sources on faith. Before gaslight and then electrical lighting, Brox writes, “light — however meager — had always been one’s own and self-contained within each dwelling.” In the wake of the gasworks and the generating plant, though, light became something “interconnected, contingent, and intricate…. It marked the beginning of the way we are now, with our nets of voices, signs and pulses, with power subject to flickers and loss we can’t do anything about.” The 21st century has the potential to become a new Dark Age — except we’re all less self-reliant now.

As I write this, Concord, Mass., is taking down hundreds of streetlights on side streets and rural roads to cut costs while reducing its carbon footprint. Emerson, the sage of Concord, who compared the evolution of lighting with moral progress, might be dismayed to learn that those who wish to keep a light shining in the darkness have the opportunity to do so — if they can afford $17 per streetlight, per month.