WHERE THEIR FIRE IS NOT QUENCHED (5)

By:

January 31, 2024

May Sinclair’s “Where Their Fire is Not Quenched” was first published in the English Review in October 1922 and later appeared in Sinclair’s 1923 collection Uncanny Stories. It has frequently been reprinted in supernatural, horror, and fantasy anthologies; I’m grateful to Paul March-Russell, whose Modernism and Science Fiction encourages us to think of Sinclair as also being a proto-sf author. (PS: Interesting to compare this story’s ending with Sartre’s No Exit, p. 1944.) HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize it here for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10.

After enlightenment the rupture.

It came from Oscar, one evening when he sat with her in her drawing-room.

“Harriott,” he said, “do you know I’m thinking seriously of settling down?”

“How do you mean, settling down?”

“Patching it up with Muriel, poor girl…. Has it never occurred to you that this little affair of ours can’t go on for ever?”

“You don’t want it to go on?”

“I don’t want to have any humbug about it. For God’s sake, let’s be straight. If it’s done, it’s done. Let’s end it decently.”

“I see. You want to get rid of me.”

“That’s a beastly way of putting it.”

“Is there any way that isn’t beastly? The whole thing’s beastly. I should have thought you’d have stuck to it now you’ve made it what you wanted. When I haven’t an ideal, I haven’t a single illusion, when you’ve destroyed everything you didn’t want.”

“What didn’t I want?”

“The clean, beautiful part of it. The part I wanted.”

“My part at least was real. It was cleaner and more beautiful than all that putrid stuff you wrapped it up in. You were a hypocrite, Harriott, and I wasn’t. You’re a hypocrite now if you say you weren’t happy with me.”

“I was never really happy. Never for one moment. There was always something I missed. Something you didn’t give me. Perhaps you couldn’t.”

“No. I wasn’t spiritual enough,” he sneered.

“You were not. And you made me what you were.”

“Oh, I noticed that you were always very spiritual after you’d got what you wanted.”

“What I wanted?” she cried. “Oh, my God—”

“If you ever knew what you wanted.”

“What — I — wanted,” she repeated, drawing out her bitterness.

“Come,” he said, “why not be honest? Face facts. I was awfully gone on you. You were awfully gone on me — once. We got tired of each other and it’s over. But at least you might own we had a good time while it lasted.”

“A good time?”

“Good enough for me.”

“For you, because for you love only means one thing. Everything that’s high and noble in it you dragged down to that, till there’s nothing left for us but that. That’s what you made of love.”

Twenty years passed.

It was Oscar who died first, three years after the rupture. He did it suddenly one evening, falling down in a fit of apoplexy.

His death was an immense relief to Harriott. Perfect security had been impossible as long as he was alive. But now there wasn’t a living soul who knew her secret.

Still, in the first moment of shock Harriott told herself that Oscar dead would be nearer to her than ever. She forgot how little she had wanted him to be near her, alive. And long before the twenty years had passed she had contrived to persuade herself that he had never been near to her at all. It was incredible that she had ever known such a person as Oscar Wade. As for their affair, she couldn’t think of Harriott Leigh as the sort of woman to whom such a thing could happen. Schnebler’s and the Hotel Saint Pierre ceased to figure among prominent images of her past. Her memories, if she had allowed herself to remember, would have clashed disagreeably with the reputation for sanctity which she had now acquired.

For Harriott at fifty-two was the friend and helper of the Reverend Clement Farmer, Vicar of St. Mary the Virgin’s, Maida Vale. She worked as a deaconess in his parish, wearing the uniform of a deaconess, the semi-religious gown, the cloak, the bonnet and veil, the cross and rosary, the holy smile. She was also secretary to the Maida Vale and Kilburn Home for Fallen Girls.

Her moments of excitement came when Clement Farmer, the lean, austere likeness of Stephen Philpotts, in his cassock and lace-bordered surplice, issued from the vestry, when he mounted the pulpit, when he stood before the altar rails and lifted up his arms in the Benediction; her moments of ecstasy when she received the Sacrament from his hands. And she had moments of calm happiness when his study door closed on their communion. All these moments were saturated with a solemn holiness.

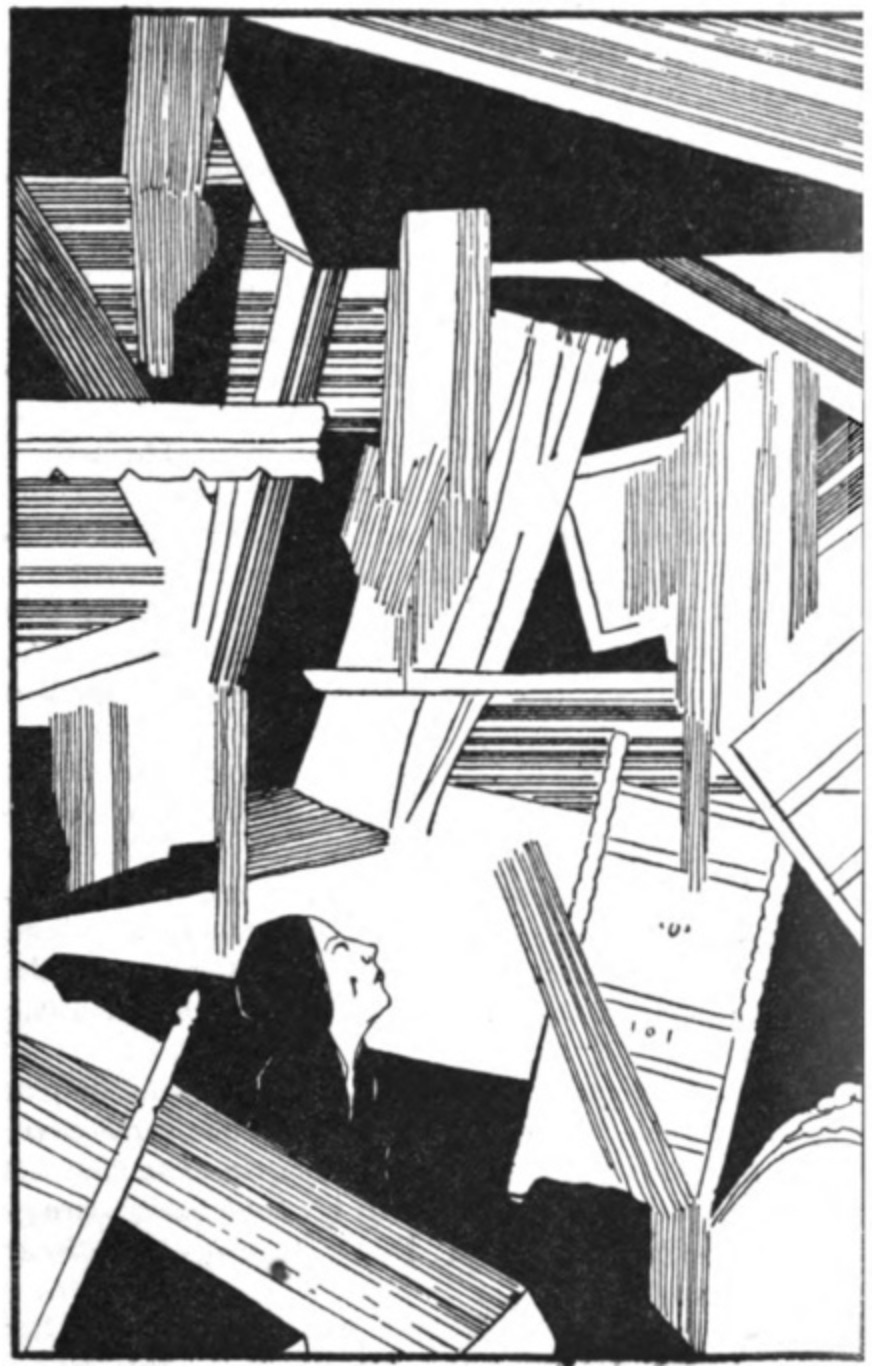

And they were insignificant compared with the moment of her dying.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.