INVADERS FROM OUTSIDE (4)

By:

October 1, 2023

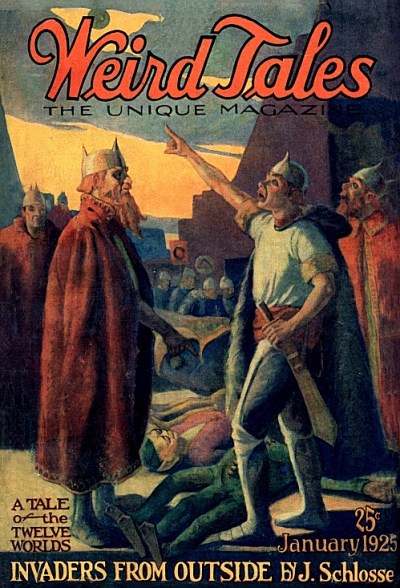

J. Schlossel’s first story, “Invaders from Outside,” appeared in the January 1925 issue of Weird Tales. It was one of only six stories that he’d publish. SF historians agree that — with its solar system of inhabited planets, a council of worlds, and a space battle between fleets of ships — the story is an early example of “space opera.” HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize it here for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.

The first reports, though not officially confirmed, came at last from Japetus. Its distance was estimated to be a little less than the distance that it takes light to travel in half a year. It was much farther away than the first wild reports had led them to believe. Later came its size, speed, and direction.

It was generally considered that it was a dead world — a piece of slag — hurtling through space at the incredible velocity of eighteen thousand miles a second! Just one-tenth the speed of light. At that speed it would be upon them in less than five years!

Its diameter was ascertained to be about two thousand miles, or one-fourth the diameter of the planet Earth. It was nothing but a tiny speck as stellar sizes go. Small as it was, at that rate of speed, it was large enough to wreck the civilization of the solar system. The question that naturally came to the inhabitants of those twelve civilized worlds was: was it only a burnt-out cinder thrown off by some mighty sun with such unerring aim and such great force that it should flash through the heavens straight for the solar system? Or was it inhabited by sentient beings?

A reassuring official report was sent out. It said that there was absolutely no cause for alarm; that when the approaching body reached the spot in the heavens where the sun and his attending planets now were, the entire solar system would have moved on many hundred million miles away on its own course. At the rate of speed with which the approaching body was traveling, the attraction of our sun could not swerve it from its course; no, not even if our sun were ten thousand times his own size.

The astronomers welcomed its coming. Its speed was an unexplainable phenomenon of the heavens. “Nothing but a head-on collision with some larger body could stop it,” they declared.

All its surface peculiarities were known by even the youngest inhabitant of the Twelve Confederate Worlds. It was as smooth as a billiard ball — proof of its great age. A snowlike substance covered its surface, probably to a depth of five hundred feet. But the knowledge conceiving it extended no deeper than its surface.

If their instruments could have seen beneath the snowlike covering, seen what was going on there, the Confederate Worlds would have begun feverish preparations for one of the most desperate struggles that had ever been fought.

They thought of tracing it back. At that speed (so they reasoned) nothing could have turned it from its course, and so it must have come almost as straight as a ray of light. But they were wrong, very wrong, for its flight was not governed solely by the mechanical laws that govern matter. The Confederate Worlds made no allowance for such a thing as a directing will. If they had known of its curious zigzag course, could they have accounted for it? They knew no laws to explain why it should swerve sharply aside when it came into the neighborhood of some of the mighty suns that had dotted its course as it flashed on its way toward the solar system, and then, after passing them, resume its former course. Instead of repulsing, those mighty suns irresistibly attract any wandering bodies that chance to come within the field of their influence.

It was impossible to trace back its course, but if they could have done so. they would have been dumfounded at the immense distance that the approaching body had covered.

It was a visitor from a far off region, indeed. Out beyond the borders of the Milky Way the star clusters gleam as thick as the stars shine overhead on a clear, frosty night. But they do not shine with the sharp brightness of nearer stars. It is their distance, impossible to comprehend, that makes them appear nothing but a patch of soft, hazy light, notwithstanding the fact that each cluster shines with the combined light of fifty thousand to one hundred million, huge flaming suns!

Everything must in time grow old. The living take their substance from the dead. The suns grow old and die. Everywhere in the heavens the ruins of dead star clusters can be seen — huge, shapeless masses that are absolutely dead-black.

And that approaching world and many others had come from somewhere out there, not from a living, glowing star cluster, but from the outskirts of a dead, intensely black region. From a region, if such a region can be imagined, where all matter has nearly reached a state of perfect equilibrium. Where all matter is nearly stable, and so all matter almost dead. There were no flaming suns there to give light to that terrible darkness. Each body within the borders of that lifeless region was breaking down. The molecules were disintegrating, the atoms flying free. In the boundless sea of ether the atoms were moving sluggishly away in vast, cloudlike masses. This was the end of a universe.

Like slinking rats from a sinking ship this approaching body had come from that region. It came with a grim, fixed purpose, nearer, still nearer. It was invisible to the naked eye. It was calculated to soon pass the solar system.

Some of the more hot-blooded members of the Scientific Society of the Twelve Confederate Worlds requested permission to take one of the society’s interstellar vehicles, provision it for a lifetime, and go out to meet and board it. They painted in glowing pictures the advantages that the Scientific Society would gain from their sacrifice, and the perfect descriptions that they would be able to broadcast back.

Their request was refused on the grounds that the new Martian instrument for observation installed upon Japetus could easily follow its flight for ages to come. It would be only a useless sacrifice of life to attempt to board that strange object.

In the secret code of the Scientific Society word was sent out that this body had actually stopped in its headlong journey. It hung poised, motionless, then began to fall slowly toward the solar system. These new and terrifying facts were not given to the general public. It would not help matters if they knew, but might bring on another attack of hysteria. The Scientific Society could hardly believe the evidence of its observation instruments.

The body continued to drop slowly toward the sun, and then, as it neared the orbit of Neptune, it turned, and at an acute angle it began to head for old Neptune, who was crawling out of the west to meet it. A collision seemed imminent. Its speed was very slow, no more than eighteen hundred miles a minute — just a fraction of its former tremendous speed, and it became still slower. When the newcomer came within a quarter of a million miles of Neptune it began to circle him, as if it were a moon.

The Scientific Society heaved a sigh of relief, and gave out the facts then to the public. The changing speed and the deliberate actions of this new member of the solar family were unexplainable; still, all the threatened danger seemed past.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.