Memories of the Biosphere

By:

December 1, 2011

This article was first published in Hermenaut #15 (1999). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

Columbia University puts its most valuable asses on the line… — Typo on the Biosphere 2 website.

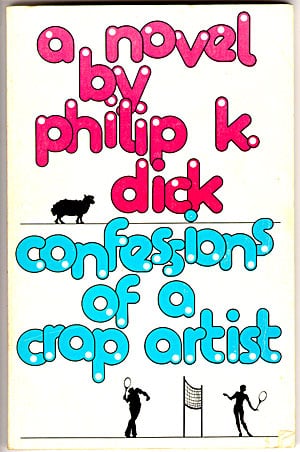

That nut. A family of nuts. A world of them. — Charlie Hume, in Philip K. Dick’s novel Confessions of a Crap Artist

The sorry fate of Biosphere 2 is a good example of something so dear to Philip K. Dick: that technology, no matter how inspired, cannot keep humanity from falling back on its crudest instincts. You remember Biosphere 2, the $200 million-plus laughingstock of the scientific community. It was the brainchild of a “Texas billionaire” named Ed Bass — the kind of Texas billionaire it’s all too easy to picture (at least I’m picturing giant horns strapped to the front of a Cadillac). A few years ago, after the ‘Sphere was abandoned and left a chapter in the annals of crackpotdom, Columbia University bought it for a mere $1 million — a decent price for Arizona real estate that includes an indoor rain forest, an ocean, and five other separate and distinct ecosystems — and certainly far less than B2 cost during its brief tenure as a trial run for interplanetary settlement. But I get the impression that no one else wanted it — like, oh, that old thing. Well, a lick of paint and bob’s yer uncle: the Biosphere 2 Center!

Where once existed a 240,000 cubic-meter “space frame” megalith in the middle of the desert, there are now a Columbia U.-run hotel, restaurant, gift shop, and cybercafé. All traces of the site’s previous incarnation have been obliterated: This is, as we all know, the standing definition of progress.

The Biosphere 2 Center website asserts the various “educational merits” of the Center and even has a Help Wanted page listing positions like line-cook, housekeeper, and something called “interpretive tour guide”-job hunters, take note! Mostly there is a recurring insistence that the ‘Sphere has somehow graduated from “pseudo-science” to “credible science,” which is evidently that realm where families of tourists behold in wonder ecosystems under glass. Kind of like Epcot, but full of insects. It’s in this shaky endeavor that Columbia has put its asses on the line, attempting to put your ass in a hotel bed starting at fifty bucks a night. Cheap!

But if you only visit the website, don’t forget to check out the Volvo-Columbia Partnership page. Never mind that Columbia claims its prime directive is the study of greenhouse gasses. This may seem as paradoxical to you as it did to me — slow carbon-monoxide suffocation of the planet, automobile manufacturer as major sponsor — but I’m sure they have their reasons for the unholy alliance. I’m just not sure I want to hear them.

What happened at the Biosphere’s inaugural inhabitation in 1991 is the stuff of empirical legend. A group of scientists, four men and four women, were to seal themselves in for two years without any contact with the outside world, there to grow their own food, and live peacefully together as future pioneers in a harsh and alien (well, kind of alien) climate. Unfortunately, the outside world had to intervene a few times: to get rid of an ant invasion, to pump in oxygen, to tend to a health emergency or two, to bring in forgotten necessities like makeup. The scientific team managed to last out the term, but they were half-crazy and half-starved when Ed Bass and the US Marshals finally came and busted them out. Despite the fact that they were all carefully chosen on points of age, marital status, and (I reckon) personal grooming, during their debriefing the scientists revealed that they’d found it impossible to live together in such close quarters, and that by the end they hadn’t even been speaking. One marriage did occur after the fact, so this Dating Game approach to science apparently had some success.

The scientists mostly reported power struggles, lots of bickering, and of course the much-anticipated sexual tension. It was all quite catty and perverse. I myself would love to be sealed in a sphere for two years with, say, Ralph Fiennes and Jean-Paul Belmondo, frolicking to and fro in the marsh and savanna. Maybe Jerry Lewis could come visit on the weekends for some comic relief. Jean-Paul might like this, but poor Ralph would probably be beside himself — and put out that bloody Gauloises! You see, you don’t have to be Steven Hawking to figure out what really went wrong at Biosphere 2. But for some reason, Columbia insists on reporting allegations of “cultism” among the crew, and it gives as evidence of this the fact that they called themselves “biospherans.” I daresay Columbia would do better to investigate its own fraternities for cultism. Columbia also questions the scientific credentials of the original eight (for which I cannot account), but I doubt a Texas billionaire would leave his million-dollar baby in the hands of people better suited for the Spahn Ranch. Not that I would want any of them performing brain surgery on me, but you know what I mean.

The history of biospherics goes back at least as far as the Space Race, and has always been a parallel component of our rush to the stars. In 1961, a Soviet scientist by the name of Shepelev was apparently the first to undergo a “human biospheric enclosure,” when he sealed himself in a steel cylinder with nothing but eight gallons of algae. By these standards, Biosphere 2 was the Chartres cathedral of such endeavors.

Amid the photos and travel pitches, the Volvo logos and Columbia puffery, the current Biosphere 2 Center website makes one thing perfectly clear: This is family entertainment. No commune-ists, visionaries, or future interplanetary pilgrims here! No doomed-to-fail, crackpot science allowed! I can only think it — at the very least — unsporting to question the scientific purposefulness of the original biospherans, especially when Columbia offers as an alternative a Disneyfied entertainment complex run under the pretext of studying the effects of greenhouse toxins on the environment. Gee, I wonder if they’re bad, those gasses? Can we do anything about them?

This is science-lite: a cheerful, never unpalatable expression created to relieve and not alarm the visitor about the future of Biosphere 1, Planet Earth. Maybe next Exxon will buy the Sierra Club to study the effects of littering. Does the Hasty Pudding Club run a dinner theater at Los Alamos? Put on these glasses, folks, you’re in for quite a show!

A travel article by a writer named Theresa Lee and originally published in The San Francisco Examiner is the website’s pièce de résistance. Theresa and her husband were seeking a holiday suitable for two children “too old for theme parks” but who “still don’t have the love for landscape adults develop later in life.” They wanted something “real” in their vacation so naturally they chose the Biosphere 2 Hotel for the weekend. When the Lee family wasn’t busy watching tv or “surfing the Internet” at the hotel’s cyber café, they admired the rain forest “pressing against the glass” and toured the desert “where we could view the cacti from our air-conditioned car.” Then they relapsed and went on some movie-studio tour in Tucson. After a swim in the pool, Theresa solicited her children’s opinions on Biosphere 2. Her daughter was especially interested (future P. K. Dick reader), but her son thought the whole thing a colossal waste of time and money (future Columbia U. alumni association contributor). I could just picture the whole family arguing over the Game Boy.

All this family fun reminds me of Philip K. Dick’s best and most urgent work, a non-sf novel called Confessions of a Crap Artist. Its closing chapter is much like Theresa’s vacation, except that after the harrowing events of the story, the family’s outing to a little theme park reaches the level of a horror movie. Dick has already by this time decimated marriage, suburbia, and consumerism by revealing the latent and actual adultery and violence lurking behind the family’s front door. At the theme park: “The howling of the children made him weary. Everywhere kids raced and screamed, in and out of the bright, newly painted storybook buildings that made up the Oakland Park Department’s idea of Fairyland… In the center of Fairyland, Little Bo Peep’s lambs were being fed from a bottle. A woman’s voice, amplified by loudspeakers, told the children to come and see.”

Only the lure of autobiography could derail Dick from his psychedelic “gloom stories” (his words) into one that is, if anything, even more depressing. The narrator is Dick himself, in the guise of Jack Isidore (a character resurrected in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep), the “crap artist” of the book’s title. Jack, an sf geek who can’t fit in or make a living, is arrested as the story begins for stealing chocolate-covered ants “for an experiment.” Bullied his whole life by his sister Fay, Jack has spent his time dreaming over pulp sci-fi magazines like Astonishing Stories and Thrilling Wonder; now he lives with his sister’s family. Jack is also the book’s sorry excuse for sanity (“Even by looking at me, you’d know my main energies are in the mind”). While all hell is breaking loose at the home of Fay and her husband, Charlie Hume, Jack seeks solace in a local UFO group who’re certain civilization is coming to an end. A small-town newspaper article on them reads: “World War Three will begin before the end of May, and not to destroy man but to save him, according to Mrs. Edward Hambro of Inverness Park, Marin County… ‘Scientists know that the world is about to explode,’ Mrs. Hambro declared. ‘Either from a build-up of internal pressures, or from man-made atomic radiation. In any case, man must prepare for the end of the world.'”

Fay, a tremendous feminist anti-heroine, and her dull, beleaguered husband Charlie live in an expensive, gadget-filled house; a protective, isolating womb; a Biosphere 2 at the end of the Eisenhower era. After describing the technologically advanced house in great detail, and enumerating its inherent structural flaws, Jack goes on: “And yet, they loved their house. They had four black-faced sheep cropping grass outside their glass slide, their Arabian horses, a collie dog as large as a pony that won prizes, and some of the most beautiful imported ducks in the world.”

Internal pressures are building chez Hume, however. When we first meet Charlie, he is enraged, having been sent out by Fay to buy tampons. When he gets home, he hands her the tampons and a tin of her favorite smoked oysters — here, these are for you — and hauls back and slugs her. Under Jack’s (and Dick’s) gaze, Fay exacts her revenge for the rest of the book. We know Dick was a writer obsessed by war; Crap Artist is not so much domestic noir as it is a war novel set in the redwoods. The corruption in the Hume family spreads out into the social fabric — the world of nuts — and by the end no one has been spared. No one survives the biosphere.

Except Jack. An outsider caught in the middle of all this, Jack does manage to survive, and Dick manages to escape pinning himself down to any one set of beliefs. Despite the not completely unhappy ending, in which Jack decides his brother-in-law is right — the world is full of nuts and he’s one of them — Dick never abandoned the world of crackpots. He always walked a fine line between respect for NASA and a visionary “people’s science” like Biosphere 2. The Texas-billionaire-funded project, studying interplanetary colonization and environmental responsibility, may’ve seemed to most people a bizarre combination of the utilitarian and the far-out; Dick would’ve applauded both angles. There’s little that captures the imagination about a botched government project like the Mir space station, for instance: It’s a leftover rust bucket doomed to crash into somebody’s house as it sheds its life-support and blazes its polluted trail back to earth. A failure, sure, but not as telling a failure as the Biosphere. If only Ed Bass had tried to duplicate the Martian atmosphere by setting his dome in Canarsie or the Meadowlands instead of Arizona. Oh, for the vaporous yellow fumes simulating the sulfuric alien skies!

Wasn’t Dick, in the end, a naturalist? The animals in Crap Artist are central; when Charlie Hume is finally driven to the last act of his rage, he slaughters the family’s entire menagerie. (Jack Isidore, in Electric Sheep, is also obsessed with animals, in his case including android animals made in factories.) California, where Dick lived and where Crap Artist is set, home to nature-loving Disney and cults and crackpots galore, is the only state that’s hunted its state bird (the California condor) to near-extinction: the few that remain live in captivity. The lines between Disney reality and Columbia-Biosphere are officially blurred. Jack Isidore: “Today, in the 1950s, everyone’s attention is turned upward, to the sky. Life on other worlds preoccupies people’s attention. And yet, at any moment, the ground may open up beneath our feet, and strange and mysterious races may pour into our very midst. It’s worth thinking about, and out in California, with the earthquakes, the situation is particularly pressing. Every time there’s a quake I ask myself: is this going to open up the crack in the ground that finally reveals the world outside? Will this be the one?”