Linda (9)

By:

July 28, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the ninth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle LINDA, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: Linda and dog-Linda, in their return to the globe, found a clearing with a smoke tree called the Conatus Obovatus, behind which was a door, beyond which was a set of rooms and tunnels. A book began to indicate a history of experiments combining squid and trees to produce a new kind of squid. Bessad, who we met previously when Linda was first taken underground, and who belongs to a team of radiographers attempting to receive a transmission of an unknown provenance, has just appeared with dog-Linda, to ask Linda down a long tunnel, and when we last saw Linda, the three had just begun to walk down it.

18.

Have you ever looked at a Cottonwood tree in the wind? The leaves all quiver and shake like a flurry of palms cupping quarters. This morning when I looked around I kept noticing how linked wind is to the way light moves. Like the wind on the water that reflects in loopy patterns on the rock it slowly cuts through, or the Cottonwood leaves that flutter almost like mirrors. I was thinking of Linda underground, and how there would be a kind of wind but no light to be bounced, that what light there was hardly traveling, bound to objects and not an element of air. I felt sorry for Linda, even though I have been patiently and methodically pushing her underground, into this sunless space.

I don’t know why I keep stealing people I barely know and imagining them. This morning I started to steal some others, but I disciplined myself, thinking it better to stay with Linda. Although sometimes I want to abdicate all tasks, to which I’ve made myself responsible to only by virtue of announcing them to others, and although I came to this place of Cottonwoods and water not to think of Linda but to think of something else, I don’t even know what, but we were supposed to come here and think of something, I have found that Linda has followed me here, that she has a certain right to my attention, and I cannot say to her that she can only be received in certain places. One wants instinctively I think to sequester the thing you are making, limit it to its proper quarters, but right now I accept that if I travel, then Linda travels with me.

For a while I lived in a very small, dark place. In the summer, in the mid afternoon, sometimes a bright shaft of light would almost enter my apartment, a thin line hitting the cabinets next to the window. I put mirrors on the window ledges to catch the light and bounce it into my house, and in the middle afternoon it would catch these mirrors and spread tentatively across the ceiling. I wished I was better at building things, imagined how perfectly the place could be rigged up under more competent hands, to channel and capture any errant light traveling the airshaft, bring it into my home. Instead of sunlight, there was artificial light from the building across the way. At nights I couldn’t block it out. The fluorescent light of the opposite stairwell pushed through the curtains I made from remnants of my grandmother’s old upholstery after she died. The curtains weren’t really wide enough, and I’d only made two, leaving the kitchen window uncovered. When I would wake up to use the bathroom in the middle of the night, I would use the spill of this artificial light to climb the two stairs that distinguished my room from the entryway. I was living there when I met Linda.

When I imagine Linda in a tunnel leading down into the earth, I like to imagine it lined veined with a natural light more like a mineral bioluminescent algae than like the sun, as if instead of ore it was possible to mine light. The globe, even above ground, is not lit by the sun but filled with sourceless light I cannot account for except to say that I picture her, like the old illuminated hunting books where a small set-piece of shrubs, trees and dogs runs into a flat and gilded plane of red and gold diamonds or reticulated silver on blue. So I arrogate a freedom to give Linda a lit soil, if she is to be deprived a lit sun. She walks, following Bessad, while dog-Linda circles between the two of them. The sides of the tunnels are made of a soft grey tissue, resembling a veined leaf, but less fragile and more dense. Along the finest lines of the tissue are the luminous veins, and Linda is reminded of the squid. Perhaps they are not veins but nerves? For it is I think true that although plants have no nerves they send nerve-like messages, and if it functions as a nerve we could call it a nerve. There is Linda, stepping softly, the tunnel becoming softer underfoot, the air more humid, and what is animal and what is vegetable, and what is vegetable and what is mineral becomes indistinct, meaningless. Occasionally warm wind comes brushing past them, with a spray of water in it. Linda turns her face away when this happens, but Bessad walks on into it, undisturbed but for a half-closing of the eyes.

They walk in silence for a long time, at least an hour. The sound of their own breathing can also be heard from without, and as they deepen they think less, and the sense that everything around them is inhaling and then exhaling becomes a full and natural idea. When the tunnel splits, dog-Linda chooses the direction. As they progress it gets darker, even though the vein-nerves grow brighter and brighter, but in such fine filaments that no light casts outwards, so now it is like walking through a night sky, made not of points but lines. They finally take a wide curve and see as they round it a new silverblue light coming up from a large, flat, underground lake. The sides of the lake are tall and severe, but at the tunnel’s mouth there is a beach. A walkway cut into the steep sides, lined with rope, can be seen, and on the other end of the lake almost too far to see with certainty, a dock and a small boat. On the beach are at least 20 other people, who Linda might have recognized as Bessad’s fellows from the radio room, had she not slipped out of the globe and returned, so briefly, to Knoxville. They say nothing, backing away respectfully to allow her to reach the shore and take in the lake. Dog-Linda barks as if to say go on, Linda pets her, and dog-Linda licks her back. She makes her way to the walkway, and holding onto the rope, begins to make her way to the dock, while Bessad and dog-Linda and the others stand on the beach and watch.

The lake is not like any of the underground lakes I have been to, even though I have several times tried to lead my stories toward Wookey Hole, an old lake-filled cave in Somerset, England, that is planted in my memory. Wookey Hole these days is home to a light show and too many souvenirs, but I remember it as a simple place to be lovingly afraid of the dark. The name Wookey might make you think of Chewbaca, but that’s only a coincidence, for the names are unrelated, and the Wookey of the hole much older than the one of the movie. I always thought the name Wookey came from a bad old legend on the edge of truth, but in fact it just means “cave,” in Welsh, just as the word “hole” means cave, once spelled “holl,” as in “hollow,” which means Wookey Hole is really called Hole Hole, or Cave Cave, a kind of superlative type of hollow. Beyond the first few chambers, Wookey Hole is filled with water, but it is possible to take a boat onto its subterranean lake, just past the remnants of Roman coin and Paleolithic Man. When you leave, you can go to a paper mill next door and press your own paper out of a choice of pulps, or buy cheddar cheese aged in the cave, with its continuous cool temperature of perfect cellar.

This lake is much wider, much flatter, than Wookey, so it takes Linda at least half an hour just to walk its perimeter to the other side. She stops at another beach. Behind her a tunnel recedes, in its near-opening are shelves stacked with jars and vials of what Linda believes are medicines. A small dock extends from the beach, and attached to it is a boat. Bessad shouts across to her to take the boat, but there is so much echo that the sound is incoherent, and she hears clearly only the final repeating “oat, oat, oat.” She climbs into the boat anyway, and finds herself, without even rowing, borne out to the center of the lake, and then stilled somehow, floating above a low, luminous approaching mass rising in the lake below her.

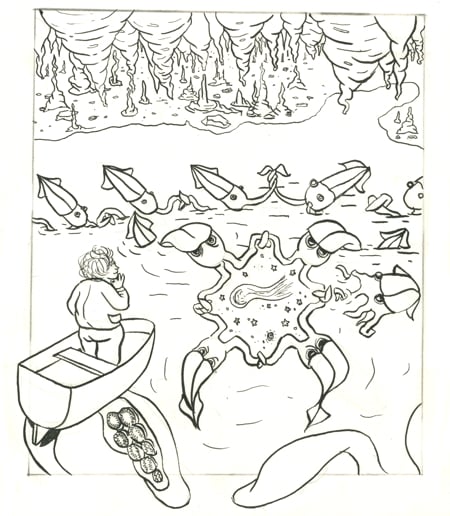

Growing up in Knoxville, Linda was never squeamish about swimming holes. She was the kind of girl that would jump in first, before the boys, even if someone had just spotted a water snake, step off the rock, press her arms to her side, point her toes and drop perfectly down. Of her habits it is maybe the fullest instance of bravery. So it is almost instinctive, as the boat comes to a stop, that she takes off her shoes and coat and pants and slips into the water. The rising mass, as it approaches, she thinks is a giant squid, or something like a squid. Its tentacles, which are many more than eight, bifurcate and branch, and it seems, with the different pulsions of its many arms, to be traveling almost against itself. Spiraling up to the surface, it comes just below Linda, nudges under her allowing her to rest on its head. Carrying her back to the dock, it nudges her off, and in the line of its pointing she understands she is to bring the medicine. She chooses from the shelf a few mason jars of something opalescent, returns to the squid, who returns her to the boat. She dresses and stands to pour the contents of the jars into the water, thinks she hears an appreciative sound bounce across the water.

The squid then releases thousands of baby squids, who shoot out from under, no more than glowing seeds in the massive water. The squid raises up so that Linda’s boat is almost sitting above the water, then letting out a kind of horn sound, cues the thousands of seeds to begin. The light in the cavern seems to dim, and Linda leans back to watch.

19.

A dream-ballet. Thousands of small squid and several larger ones. They have studied Busby Berkeley. Stop to study Busby Berkeley if you have not already. They possess the capacity to marvel. They join and chain. The chains circle. The water under their churn produces a music, a drone tone that modulates in strange spacey intervals worthy of Aram Khachaturian, but slowed way down, even beyond the speed of a slowly tumbling space station, so that it is not the music’s meter but the serene pace of the circling that seems to draw the time forward. The squid now this great corps, in luminary channels acting as a single kaleidoscopic pattern spinning underwater under Linda’s or any eye. Leaning into the water and compelled sideways by coordinated tentacles in graceful lower left pulses. This sound was already lifted for another dream ballet that had been lost in my memory until just this moment, but what dream ballet is really so much unlike any other, or at least what dream ballet possesses anything that could truly be called an edge and who can say where the last one ends and this one begins? Whether squid or elephant. Whether terrible or gentle. What is seen is circles, circles tracing a now more and more familiar shape of a set of nine orbits and a tight solid circle at the center rotating on its axis while the squid that form its solid state take continuous slow motion somersaults in minutely shifting facings. An orbital dream ballet in the style of Busby and the tempo of a weightless tumble. Then the planets enter, represented by a scheme wherein the many squid pass on raised tentacles a single juvenile squid curled in a ball, tracked by a spotter spraying continuous water so the element of air is still the element of water, and no squid suffers in the making of the image. The squid that make the sun spill apart in serpentine patterns, running their tentacles dog paddle style as if to channel the deliberateness of running serpentines done on land, until reforming as a question mark, and the sound ceases and the whole picture stops.

A dream-ballet. Thousands of small squid and several larger ones. They have studied Busby Berkeley. Stop to study Busby Berkeley if you have not already. They possess the capacity to marvel. They join and chain. The chains circle. The water under their churn produces a music, a drone tone that modulates in strange spacey intervals worthy of Aram Khachaturian, but slowed way down, even beyond the speed of a slowly tumbling space station, so that it is not the music’s meter but the serene pace of the circling that seems to draw the time forward. The squid now this great corps, in luminary channels acting as a single kaleidoscopic pattern spinning underwater under Linda’s or any eye. Leaning into the water and compelled sideways by coordinated tentacles in graceful lower left pulses. This sound was already lifted for another dream ballet that had been lost in my memory until just this moment, but what dream ballet is really so much unlike any other, or at least what dream ballet possesses anything that could truly be called an edge and who can say where the last one ends and this one begins? Whether squid or elephant. Whether terrible or gentle. What is seen is circles, circles tracing a now more and more familiar shape of a set of nine orbits and a tight solid circle at the center rotating on its axis while the squid that form its solid state take continuous slow motion somersaults in minutely shifting facings. An orbital dream ballet in the style of Busby and the tempo of a weightless tumble. Then the planets enter, represented by a scheme wherein the many squid pass on raised tentacles a single juvenile squid curled in a ball, tracked by a spotter spraying continuous water so the element of air is still the element of water, and no squid suffers in the making of the image. The squid that make the sun spill apart in serpentine patterns, running their tentacles dog paddle style as if to channel the deliberateness of running serpentines done on land, until reforming as a question mark, and the sound ceases and the whole picture stops.

Linda clasps her hands and sings out in four clear syllables from high to low and again high then to lower, “so lar sys tem.”

And the question mark unwinds and returns to form the sun, and the larger squid, the one one which Linda’s boat is resting, again sounds a kind of horn and the entire picture, still paused in its orbits, begins a small but intense quiver. The gentle anyway will yield to terrible if it concentrates hard enough on becoming elemental. The quiver lowers the pitch of the drone, becomes rumble encased by a faint shrill. The sun again unwinds in the serpentine, oldest of folk dances, holding tentacles to form now not a question mark but a word, spells out SING. So Linda sings. Because she does not know yet what she is supposed to sing she simply lets out the three notes she remembers dog-Linda howling when they found the door in the hill behind the smoke tree named Conatus Obovatus. The singing is a kind of calling forth. She sings again. And for the third time sings, and then appears on the far end of the lake a swimmer, a human swimmer, holding out of the water a cut-paper ball trailing a tail, a paper comet, and the swimmer takes arcing pathways toward the squid corps, still maintaining their orbital quiver, and glides turning over like a slowed down firecracker on an errant but beautiful path, around each planet in turn, until it reaches the sun, which still spells sing, and circling it three times catches its own tangent outwards in a direct path now toward the third planet, which glows green and then blue and then blue green. And this is how the squid tell Linda to call the comet, if she would have it come.

And Linda clasps her hands in delight.

Meanwhile, above the hollow:

When you go to the singing, you will be welcomed. They will tell you how it works and explain how it happens. If you ask about the harmonies they won’t have much to say. These open fifths and octave stretches are strange and hard sounding just as their lives are strange and hard. Once their grandparents and their grandparent’s parents lived very low and hard, at subsistence if they were lucky, reliant in bad seasons on the charity of neighbors. Now they live in subdivisions, they own TVs and cars, they buy frozen dinners and do not know much about working the land, but the love of this sound and some residually hard disappointment is in them and so they go, every Sunday, to the singing, no matter what. They are church songs but more than that the singing is a sound and a smell and they like it. Everyone brings food and after the singing is over there will be a big lunch on the long tables outside the hall. Their great grandparents sat outside to sing but their grandparents built a big square building in the middle of the hollow, with windows opening up onto the sloping banks of earth, all wood, all resonant.

When the singing starts, you sit in a square, and when it is your turn, you make your way to the center and you call the number of your song: no. 79b, Come the Darkening Down. You mark time. Everyone begins the first pass, the wordless one, singing only “lo lo lo” along the lines of the part before breaking into the song proper, and as we sing, you stand in the center and the voices of each part come at you sharp. The four parts hit your body from the four sides of the room, and only you receive the vibratory fullness of the song.

Oh come darkening down now

Oh come and darken down

I never found my home again

I never heard a sound

Our face decays in dying light

until we find the ground

Our grace it crumbles in the night

we tunnel under ground.

When I go underground,

When I go underground,

It means the darkening down has come

Oh come oh darkening down

Out of arched mouths and deep throats and pumping lungs comes this sound. How it carries over air and not only into your ears, across your cochlea, quivering across the small forest of hairs leading into your head, but goes too into your gut into the liquid in the small resilient sacs around your organs, penetrates even your omental bursa, the empty space you filled with fat, a cavity between your pancreas and your liver, from every direction vibrates across you like wind blowing from all four corners of the earth.

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, Oh Come:

NEXT WEEK: Will Linda call the comet? Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.