Linda (7)

By:

July 14, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the seventh installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle Linda, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: Linda, a retired math teacher we met in a hostel in Knoxville, has been alternately waking up in a kitchen to which she is mostly confined, and wandering around a place called the globe, with a dog named dog-Linda. In the end of Part One, she was taken abruptly underground, where a small team of mysterious radiographers were holding her while she slept, but she disappeared along with the eggshells while they were listening to her on the radio, in a transmission of indeterminate date.

PART TWO

14.

I worry I have lost Linda, just when I finally got her underground. Out the window a Western Scrub Jay has an acorn in its beak, and I don’t know how it will manage to get it down or the good of nudging it up and down the cavity of its mouth, beak-hard as it is already. Our house is surrounded by oak trees, and back in January the acorns would rain down on the roof continually, striking our heads when we stood outside, hitting car hood, roof, windshield in large startling thunks that made the dog bark. These trees dispersed vast quantities of acorns that mixed in with the white-grey gravel that covers the property. I tried to rake them, dispose of them, but they just came and came, and I gave up, demoralized by raking and weeding. Now, after many months, I have started to notice little oak shootlings in the ground. I pull them up, because demoralized or not I’m supposed to keep the gravel clean according to our lease, and the least I can do is keep it free of trees.

When you pull up a fledgling oak, its acorn is still attached, usually just nestled into the loose soil right under the surface. A root goes down, the acorn itself is split and has cast away the outer hull, and then coming out of the top is the shooter, the tree. It feels like this very strange violation, to discover an acorn still there, not yet dropped away or grown over, like finding a caterpillar mid-cocoon, and it also feels like a kind of marvel, and makes me feel stupid for never having thought about how an acorn works. That it’s necessary to drop hundreds if not thousands of acorns makes a lot of sense, what with people like me out there pulling them up, the jays, never mind the squirrels, and even my dog chews them. I wonder what we gain from commandeering these would-be trees, and worry about the waste, at least on the part of the dog and myself, because we don’t even eat them, we just break them for the sound, and then throw them away. I have kept a plate full of pulled oaks, and I plan to draw them for Linda before I finally put them in the trash, to go mingle in plastic silence with spent packaging, wherever it is our trash goes.

A long time ago when I was just starting to imagine Linda, I wrote a bunch of sentences pulled sideways and in fragments, as so many shootlings, transcribed from a notebook, now lost, a small blue leather book written almost entirely in green ink with a few planet stickers off a party favor sticker sheet from my friend Amber’s wedding, and if you find it please let me know. I don’t remember much of what I wrote in it except the repeated expression of thankfulness to a particular stretch of forest in the park near where I used to live, before I came to the place I live now, which is actually a real forest, although forests in California are not necessarily full of trees, but rather scrub, shrubs, the most beautiful thickening, circling, flowering scrub imaginable.

I found the sentences.

(1) And electric light ducks multiplied in all the lakes.

(2) Everyone get on headset and acknowledge Linda.

You get the feeling they don’t really want to be sentences, that despite the appearance of subject and predicate, the planting of a period is a kind of violence, arresting what would rather be floating. Do you know about Gertrude Stein, who loved to pile up things and shine light all over them and never use commas? She said that paragraphs were emotional, but that sentences were not, and I thought, yes paragraphs are emotional, but can’t a sentence also be emotional? If what we mean by emotional is the piling up of things, can’t a sentence also pile?

(1) We owe the morning our full feeling when a new sports bar sings in a way we don’t like the sound of.

(1) There it is, singing.

(2) I found the spot on the leaves.

Even looking at these sentences makes me bodily remember the light in that old city and the feeling of being squashed and waiting and unable to receive Linda.

(1) It is too hard in the dark to go down the road tired and hoping or talking as usual of more light or horse hooves or panic about offending the crowd.

(2) You find something in front of you.

(1) She smoothes down the pages.

(2) She covers over the table.

(3) She dusts them with a strange effect.

(4) Leaves start falling then stopping mid air.

(1) How should it watch?

(1) Linda uncovers a wood treasure but will not stay near if I stomp my foot.

(1) I do it as if I have authority when really I am not appealing to my own or anyone else’s dignity.

(2) That sound is an intruder below the noise of this building.

(3) That noise comes from below the building.

(1) Apparently there was nothing serene there but the swath of sky sometimes or the kind of moon we had last night or the windows of other people’s houses.

(1) Space causes this varietal kindness.

(2) I know I’ll be late but these are sentences.

What are the numbers for said Linda one time, and I said, I don’t know or I don’t know yet or I think I know but I can’t say yet. But I realize now that the numbers are like notes, like musical notes, so if you go back and read the numbers again you can imagine a vibraphone playing as enumerated four perfect notes that form a kind of succession, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 1, 1, 2: a kind of sequence that when you hear it makes you feel light and makes you feel you might be moving, might be going somewhere, just now launched.

I have to clean myself and go to work.

15.

I found Linda.

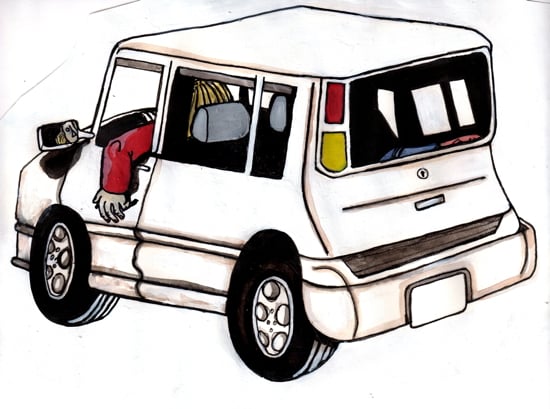

She’s in the van, driving west from Tennessee, listening to “Dirty Work” on repeat. She won’t talk to me, I think because she doesn’t know I’m here, hears nothing above the Steely Dan. She is going 80 on a country highway, and as it is now spring, the tall grass and wildflowers make a kind of white and yellow blur out the window behind her.

Next to her is a stack of free newspapers, the kind local advertisers pay for, with coupons and incidental features on regional offerings. Al made me take one when he dropped me at the airport on the way to the singing, despite the fact that I was right then leaving Tennessee to go back to New York City and had no more use for the coupons. I might have appreciated the paper when I had arrived in Knoxville, where in a cab from the airport shared with two older academics, the lady driver suggested things like where to eat barbecue or take day trips. When I moved to the front seat on the last leg of the trip, from the hotel to the hostel where I was staying, she showed me where she carried business cards for a local pimp. She said people mostly wanted to know about barbecue but sometimes also escorts and she certainly didn’t approve, but passed on the number because as a taxi driver from the airport she was a kind of ambassador and wanted to help.

According to Al, Knoxville is so corrupt that the pimp’s number may as well have been listed right in the paper, a special advertising section between Dollywood area motels and country apparel, its digits in bold type over a photograph of a promising blonde waving at Linda from the wind-rummaged stack flapping at her as she drives open-windowed down the highway away from Tennessee. She has gotten as far as Missouri, I think, and I have sent her there mostly because I have been there, and so can imagine the particular shades of green and the width of the highways and the small lake diving docks and the ranch houses with all night card games going, just behind the trees. She stops at a gas station for a soda and to pee and to look at the sky, and feels a kind of amazement at her escape, and a kind of peacefulness, and begins to think again of what she can do now that she has no obligations. Returning to the car, the sun lowering in the sky, she flips the radio to AM and drives through a town, past closed antique malls and streets torn up for utilities work. A community station is running classified announcements of barns for sale, truck parts, tractor parts, land. A man comes on offering a baby shark in a jar for $50, and Linda thinks she would really like a shark in a jar, but not enough to stop the car, not enough to stop moving. If she stops, she senses, she will be liable to a rush of memories from weird corners of that life she is driving away from – not the globe life but the Tennessee life – unimpressive memories of banal things are already pressing at her mind and only driving will keep them down, along with the bile. She imagines Missouri as the fulfilled hope of a sleep lying all the way down, a life free from the taste of her gut.

When Linda awoke in the kitchen after disappearing from the globe, she slowly realized, leaning against the fridge, that the kitchen was changed. That the light coming through the windows was of a new intensity, and that the dead computer had the innocuous hum of function, a hum cutting frequencies of television sound feeding in from the other room. She walked into the common room and saw Anders, or Andros, or something like that, the accident-prone Dutch backpacker with the broken hand, watching a PBS special on Josephine Baker. Al was in the hallway on the phone taking a reservation, and when she went to the ladies dorm, she saw the pillows all upright on her bottom bunk, and her tinctures and mending kit and wool socks, and my apple green suitcase half slid under the other bed. After a moment of cautious joy she moved back through the house, returned to the kitchen. She sat down at the computer and wrote an email to her granddaughter promising to tell her about the night sky above the Grand Canyon, then glancing back, took the van keys from the counter, and opened the door. She saw the concrete ballasts of the freeway and the flocks of birds floating on little gusts in the white sky. She stepped from the path to the sidewalk, opened the van, and drove away.

She would like, I think, to just keep driving. But I can’t let her. Sorry, Linda.

And so to her radio, I phone in this request: the Wilburn Brothers singing the old murder ballad, “Knoxville Girl.” I’d like to dedicate this to Linda.

“I met a little girl in Knoxville/A town we all know well/

And every Sunday evening/Out in her home I’d dwell.

We went to take an evening walk/About a mile from town/

I picked a stick up off the ground/ And knocked that fair girl down.

She fell down on her bended knees/For mercy she did cry/

Oh Willy dear, don’t kill me here/I’m not prepared to die.

She never spoke another word/I only beat her more/

Until the ground around me/Within her blood did flow.

I took her by her golden curls/I dragged her round and round/

Then threw her in the river/That flows through Knoxville town.

Go there, go there, you Knoxville girl/With dark and roving eyes/

Go there, go there, you Knoxville girl/You can never be my wife.

I rolled and tumbled the whole night through/My dreams were living hell/

And then they came from Knoxville/And carried me to jail.

I’m here to waste my life away/And time is passing slow/

Because I killed that Knoxville girl/The girl that I loved so.”

When I wave, Linda pulls to a stop on the side of the road, and lets me climb into the van. I can see that she’s been crying. She leaves the keys in the ignition when I ask her to get out of the van. I give her my sweater. The road she has been on cuts through a huge forest, and we turn into this forest on foot and start walking as the song changes and the lights fade and all the pirates pause their hijacking, and birds swallow acorns, and your heart grinds to a tiny, momentary arrhythmic halt and then vibrates and picks up again, while the journalists are detained and the earth, which has been warming, starts to cool, and Linda, who is no longer crying, remembers her friend Jane, a Knoxville girl too, and remembers what it looked like at dawn when she had been up sleepless all night, and how it felt to run the 440 relay and the soft rubber bounce of the track, and the way her brother’s hair grizzled at 40, and the dun color of the first horse she rode, and the smell of her husband and the light in the kitchen of the house they bought together, and the odor of bitter herbs mixed with bile, and the whistle of her breath when she would run past flowering trees in the summer heat, her throat closing and her heart racing. When we come to a stream, she stops and looks at me and I stop walking, and she walks across it and goes on, and as I pause, watching her walk into the distance, I am pretty sure that I see dog-Linda appear in front of her, licking her hand and welcoming her back.

I return to the van. I return the van to Tennessee. I fly home. When I get home, I go straight to the garage, put my headphones on, and listen for Linda.

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, Everyone Acknowledge Linda (multi panned better on your stereophonic headphones):

And for good measure, the Wilburn Bros. singing “Knoxville Girl”

NEXT WEEK: The globe gets serious and begins to show itself. A strange, radiant variety of squid enter the scene. Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.