Linda (6)

By:

July 7, 2011

HILOBROW is proud to present the sixth installment of Karinne Keithley Syers’s novella and song cycle Linda, a hollow-earth retirement adventure with illustrations by Rascal Jace Smith. New installments appear every Thursday.

The story so far: Our heroine Linda has been out walking on strange tours in a semi-real place called the globe, a forest of some kind. Early and vague clues to purpose: the eggshells and the singing (no further elaboration as of yet). In the last episode we drifted behind a picture of Linda and met a young girl sent to pick watercress amidst cow fields, and wanting to enlist the cows to sell chamomile to inhabitants of planets beyond the moon, but we abandoned her to return to Linda. Linda, out walking in the globe with the dog named dog-Linda, at the end of the installment discovered a decoy shrub that was really a manhole on the surface of the globe, and awaking some men hanging out right below the hatch, was snatched and taken underground. All this time she has been carrying around in her mouth an unidentified metal object shoved malevolently between her molars while she was half asleep.

12.

Standing amidst the cows, the girl indicates her stomach, then mimes an extensive and detailed episode of eating roasted meat still part-covered in hair, continuing from troubled mastication to the aborted digestion, the approach of intense nausea, the dry heaving and then the hacking up of the offending substance, and the exhaustion along the line of muscles that band the throat to the stomach.

(The cows respond.)

The problem is that no tea will really help these troubles that come on like a passing cloud and then declare they are here to stay.

(To this the cows do not respond: their stomachs being famously strong, they cannot emotionally grasp the unbelievable sadness produced by the stomach’s rejection; can neither emotionally nor conceptually grasp it – cannot get inside the feeling. Chewing continues. And continues.)

Will the girl never sell chamomile or watercress to the aborigines of any newly discovered planet? It seems cruel and arbitrary to prevent her from it, when anyway all these things are animated almost only by our willingness to think them. She kicks rocks as she walks back, no longer to the castle, but past the cow patties away from the watercress streams and onto St. John’s Road, past the red brick primary school and the further off upper school approached by a row of concrete pylons asking only to be leap-frogged, the houses filled with books, the beer drinkers in the Mason’s Arms, the nasty swan in the beck reported to have broken arms in defense of its privacy, the Iever’s house where babies with opulent Scottish names are sleeping outside in their prams for the good of their lungs, past the weeping willow tree and the council houses, the shale wall of my worst knee skinning, turning opposite the church into the Hargreave’s house, which she cuts through, past their rabbit hutch, and up the sloping back yard, over the fence, crossing kitty corner to my house, which is next to the house where the cat named Soda lives in wait for my brother to leave his window open and his goldfish exposed, for it is his fate to lose a string of goldfish just as it will be mine to lose a string of hamsters to the tragically abortive average stay of the store-bought animal. The girl climbs in through my brother’s window just as Soda will, malevolently knocks his goldfish bowl to the floor, turns out the door, the other way from the small bathroom where piranhas hide in the pipes, dropping bundles of watercress on the floor of the kitchen where my mother with her long black-brown hair is cooking onions, and goes to the television, sits down and wrests the Atari joystick from my hands and runs my Pacman directly, intentionally into the ghost Blinky. Sound of withering Pacman. I scream and hit back. She has no right to come here.

13.

It is dark. Linda lies deep underground on a makeshift bed, curled around dog-Linda who warms her belly. She moves, feeling for a cup of water, and dog-Linda lifts her head, then returns it to the cotton mass of blankets. Linda reaches above her head and feels the whitewashed earthen wall, senses the smoothness of the paint covering the less ordered cut-away dirt, senses even in all this darkness that it is whitewash. She stares up into the darkness of the space above her head, imagining, in place of a ceiling she cannot see, a high-reaching tunnel that opens up to the night air, and gives way to a scaffold that tunnels up through the empty air, a hole through a hole, into the sky, leading all the way to the upper part of the atmosphere where messengers bodied only with plastic tubing and discarded house keys and butterfly-type wings, are zooming around in an enormous chart of innumerable intersections, a forest of thumbtacks and string resting without anchor in three-dimensional open space.

This vision has never come to her before, has never come to me before either, and seems strange as something to appeal to when she is so far underground. But it plays before her eyes in the darkness so that she can even see it in the traces of light and color that hang there right after closing her eyes to the imagined light. She finds in fact the picture gets clearer in the colored light generated by a hard shut of her lids. Blinking hard, Linda watches the action of the scaffold in caught moments, until it becomes like a flip book or stop motion, a fantasia of some other order of caretaking, this accounting for connections, intersections, departures, this mirror of our reticulations held up for our contemplation (for Linda feels it is a map, a record of relations, held in the upper sky). She watches the lines cross and the dots form, watching in peaceful curiosity until she sees with alarm a foot and then another foot reaching down from above her vision, slipping through the spaces in the map, between string and tack, bringing an ambiguous body to follow, climbing carefully down the scaffold. From blink to blink, this figure – she cannot tell if it is a man or a woman – traverses her vision, coming closer and closer, now making footfall on the surface of the globe and continuing now below it, moving down the tunnel, gripping handles inserted into the side walls, sometimes propping itself by straddling the space, descending toward her.

Linda realizes she should stop blinking, stop moving the image forward, and so shuts her eyes and keeps them shut, feeling for the reassurance of dog-Linda’s sternum, holding onto it as an anchor to hold steady this shutting against the approaching climber. But eventually she falls asleep, and in the spaces of her dream, the climber reappears, now she dreams him as a delicate man who makes his way softly down, descending into the room Linda is sleeping in, to sit on Linda’s bed. He gestures to quietly move dog-Linda aside, and deposits a pile of eggshells in the space where dog-Linda had lain, in the round spoon of Linda’s belly. The climber reaches into Linda’s mouth and removes the thing lodged in it, then calling dog-Linda, opens a door and they leave the room together, while her dream tunnels lower now, into a dull light below her that bodies a great indistinction.

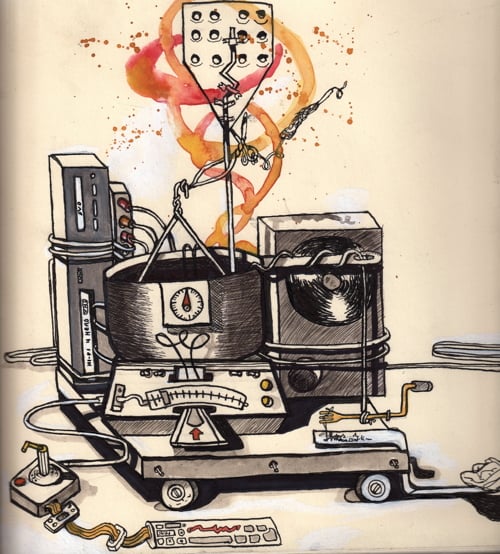

Linda is not awake, and does not see the spill of light from the hallway with its odd purple greyness, does not hear the sound of many radio transmissions or the murmur of voices, does not see the way dog-Linda is unalarmed in the presence of the climber. Instead she sleeps, lying all the way down for once, sleeps, spooning a pile of eggshells, while the climber takes the small bit of metal that was between Linda’s teeth to a room arrayed with radios and populated with concentrated people working dials far too rudimentary to register a frequency they suspect exists but cannot yet receive. The climber, whose name is Bessad, walks to his desk in the middle of the room, and fits the piece of metal into an antenna contraption that looks like this:

The static clears. He turns the dial and the room registers a pure, clean music, as everyone turns the volume of their receivers down to a hushed mumble, and gathers around Bessad’s radio.

From the radio, first a voice: a man announces in a low gravel movietone that this is KHLO, on the short waves from an undisclosable location amidst the dust, and that it is statistically just short of miraculous that you are listening. He pauses on the you, and then repeats it, you.

You are listening, he asks, aren’t you?

The room shifts, uncomfortable at the pause, feels almost an obligation to respond.

Yes, says Bessad, to himself.

And again the movietone gravelman says, miraculous.

You know, he says, there aren’t many listeners out there, anymore.

We’re working on the signal, to make it down there, since the out there no longer calls. All you listeners down there, you are a miracle. Good job.

The room again shifts. Swallows. Waits.

Yes, says Bessad again, to himself.

Now I don’t know why I keep saying “we,” since I am the solitary being in this station. We are not working on this signal, says the gravelman, except insofar as I can imagine you there, working on your reception, and so make a wager, so to speak, on a we that is working.

We are working, are we not, listeners?

The room soft. Accepts the pronoun. A small flash of vindicating pride, and then again, concentration.

But oh what a blessed relief, my friends, friend?, friends, let’s say friends, continues the gravelman, that something very rare, something I’ve been hoping would happen, but not hardly believing it would, is happening. Which is to say, I’ve got company.

The man on the radio pauses, yodels a little happy variation of the one of the songs he’s been playing on records to the dust. Ends. Resumes.

Yes I’ve got company right here in Little River. So let’s all give a big welcome to a friend from Knoxville, a Knoxville girl, come a long way.

And Linda says, thank you.

(Though we haven’t much heard her voice, if we had had it in our ears we would notice now that it comes through the radio changed. The edge of frustration is off, the one that comes from feeling, for example, like her son is screening his calls, or the funeral parlor is trying to sell her on too luxe a package. She speaks with more purpose, more pleasure, even more license, than she once did, sounds somehow like experience has changed her, although late in life, into something more powerful and far more glad.)

And Linda says again, thank you. It’s nice to be company, she says. It’s been a while. I’ve not even had the company of my dog friend, says Linda.

(Bessad’s hand moves to dog-Linda’s head. Dog-Linda’s head presses Bessad’s hand.)

Well that is hard, says the gravelman, and lets out a whistle as if calling a dog, but nothing comes, so he fills the silence with a humming-through of what he already sang. But Linda, he resumes, Linda – what I want to know is, how did it feel?

Linda’s voice now is soft. I felt at first like I just didn’t even exist. Like I had been packed in ice, as if I’d be useful in the future but for now I had better not bother anyone, and since I would most likely bother someone, it would be better I was packed up. Not that I could point to any event like that. It was more like, when I started on this, when I started walking, my body felt like it had gone through a freeze, a freeze I couldn’t remember happening, could only feel it as it was dropping away. I tried to be good. I have always been reasonably cooperative.

Well of course you have, says the gravelman. No one ever said you weren’t.

But I felt a lot like my body wasn’t my own. Like even my dreams weren’t my own, like they came into me from another head, somehow. That I would be awake and moving without having made any of it myself, even the walking I didn’t make myself.

Now Linda, wait a minute, he says in a voice made only for the microphone itself, only for the imagined ears cupping well-traveled airwaves, wait just a minute Linda, you mean you were walking without doing the walking yourself? Because pardon me if I am mistaken but I think you had to walk yourself here.

Yes, says Linda. I did.

The room, a collective further-curving in of spinal curves toward the radio, tries to understand her meaning.

Yes, I learned how to walk again. I invited myself back.

The room breathing.

And when did you get the idea that you were the one who had to do the inviting, Linda?

After I met the colonel, she says, and the room beneath the globe all startles.

I found him at the water. In the globe. Or really the dog found him. Or found his dog. The colonel has a dog, an enormous white long-haired dog. We saw it across an arm of water, like it was standing sentry on a ghost palace or something. Like it should have been made out of jade. Or white jade. Is there white jade? That doesn’t make sense. But you get my idea. It was fantastic, this dog, it was a beautiful dog. I would wake up in the kitchen and the door would open and the dog, my dog friend, not this white jade ghost dog, would be waiting beyond the door, and we would go out walking, looking for the other dog.

(If you want to imagine what Linda’s voice sounds like as she tells this, imagine that she is without noticing it, moving her mouth closer and closer to the microphone, headphones feeding her own voice back into her ears, discovering the treasure of the radio man, and as she talks she gets closer, and her voice more ambery, almost like she’s singing secretly to herself, and the more she hears herself, the more she is in the globe’s diffuse light again, flickering softly between a pearl white and a silver green, behind the trunks of the trees, and experiencing as if in a performance the crowd of everyone who will ever care about the history of Linda who walked in the globe and saved us from peril, experiences the energy of the entire crowd as if not readers of a far-distant future but an audience present at the scene, reverent and unknowing and patient and glad, breathing with extreme quiet so as not to disturb her steps as, down the royal softness of the fulfilled scene, she steps toward the colonel, a man sitting meditating by an arm of water, passing the dog who guards him in the manner of a ghost palace sentry from another culture’s mythology, to approach him and sit.)

And he had summoned you? asks the gravelman. What did he say?

Linda’s eyes blink open. Returns from the sound of her voice addressing herself to the man with the movietone gravel voice.

It follows now more like an interview, and the room beneath the globe as they learn of it more and more tentatively excited and relieved that maybe the next stage has come. They listen. Linda, gravelman, Linda, gravelman:

He didn’t say anything. He didn’t? No. I remember the dogs sat on either side of him. And how long did you sit there? A few days, I think. Did you eat? Yes. Sometimes a man brought me food. The colonel’s assistant? I don’t know. But there was a man who sometimes brought me food. Can you describe him? Oh, maybe mid- or late-40’s. Navy wool sweater. Boots, sort of an ex-military farmer I think. Very dark hair with a bit of grey in it. Slender. And did he ever say anything? No, he just brought food. Normal food? Yes, sandwiches, soup, that kind of thing. What about the colonel. What did he look like? I can’t say what he really looked like. In my memory he looks exactly like a Japanese photographer I knew a long time ago in Nashville. So he was Japanese? I don’t think so, but I can’t say. In my mind his image has literally been overwritten. I have no idea what the colonel looked like. Every time I try to imagine him, I see my friend Daido. And what happened? Well we just sat together. I didn’t get tired at all. It was a feeling maybe like what hibernating feels like. After a while I began to see things. You hallucinated? No, I believe the colonel was sharing images with me. Images? How was he sharing them? By thinking hard about them. I can’t really explain it more than that. But I felt that it was he, showing them to me. And what were the images of. They were quite- Yes? Quite awful. They were – Yes, go on. They were quite gruesome. They were of the war? No. The fires? No. The dust? Yes. Why do you think he showed these to you? I don’t know. What did he want you to do? I don’t know. So he didn’t give you an assignment or any direction? In a way, but I didn’t know what it meant. What what meant? The last image was a map. Of what? It was in a children’s book, something like burrows or tunnels in space. Outer space? I don’t think so. And then? Then I woke up in the kitchen. And you didn’t know anything. Nothing. I forgot all of it. I didn’t know why I was there, or that I had been there before. What about the eggshells. What? You remember the eggshells? What? No. What? No there were no eggshells. You don’t remember the eggshells? No.

(Linda’s voice here sounds as if she is only just realizing what it is she’s saying, and sounds already apologetic, like a remorseful fake, a fraud intruded onto the royal love of a hero’s story, but says it anyway, because it must be said.)

There are no eggshells. There never were.

Bessad, alarmed, pushes through the room running frantically down the hall to the room where Linda is sleeping, pushes open the door and Linda is not there, she is not lying down sleeping, and where the dog lay, there are no eggshells.

END OF PART ONE

And now, listen to the next song in the Linda song cycle, Slip Out:

NEXT WEEK: Part Two begins, but where is Linda? Stay tuned!

Karinne and HiLobrow thank this project’s Kickstarter backers.

READ our previous serialized novel, James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox.

READ MORE original fiction published by HiLobrow.