LIGHT AHEAD (1)

By:

January 2, 2026

A little-known utopia from 1904, by a Black author, deeply rooted in the social sciences and set in 2006 — exploring the challenges and opportunities facing African Americans in their pursuit of social justice and equality in the American South. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize an excerpt for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5.

CHAPTER I

THE LOST AIRSHIP — UNCONSCIOUSNESS

From my youth up I had been impressed with the idea of working among the Negroes of the Southern states. My father was an abolitionist before the war and afterward an ardent supporter of missionary efforts in the South, and his children naturally imbibed his spirit of readiness and willingness at all times to assist the cause of the freedmen.

I concluded in the early years of my young manhood that I could render the Negroes no greater service than by spending my life in their midst, helping to fit them for the new citizenship that had developed as a result of the war. My mind was made up throughout my college course at Yale; and, while I did not disclose my purpose, I resolved to go South as soon as I was through college and commence my chosen life-work. In keeping with this design, I kept posted on every phase of the so-called “Negro problem”; I made it my constant study. When I had finished college I made application to the Union Missionary Association for a position as teacher in one of their Negro schools in a town in Georgia, and after the usual preliminaries I received my certificate of appointment.

It was June, 1906, the year that dirigible airships first came into actual use, after the innumerable efforts of scores of inventors to solve final problems, which for a long time seemed insurmountable. Up to this time the automobile — now relegated to commercial uses, or, like the bicycle, to the poorer classes — had been the favored toy of the rich, and it was thought that the now common one hundred and one hundred and fifty horse-power machines were something wonderful and that their speed — a snail’s pace, compared with the airship — was terrific. It will be remembered that inside of a few months after the first really successful airships appeared a wealthy man in society could hardly have hoped to retain his standing in the community without owning one, or at least proving that he had placed an order for one with a fashionable foreign manufacturer, so great was the craze for them, and so widespread was the industry — thanks to the misfortune of the poor devil who solved the problem and neglected to protect his rights thoroughly. Through this fatal blunder on his part, their manufacture and their use became world-wide, almost at once, in spite of countless legal attempts to limit the production, in order to keep up the cost.

A wealthy friend of mine had a ship of the finest Parisian make, the American machines still being unfashionable, in which we had often made trips together and which he ran himself. As I was ready to go to my field of labor, he invited me to go with him to spend from Saturday to Sunday in the City of Mexico, which I had never seen, and I accepted.

We started, as usual, from the new aërial pier at the foot of West Fifty-ninth Street, New York City, then one of the wonders of the world, about one o’clock, in the midst of a cloud of machines bound for country places in different parts of the United States and we were peacefully seated after dinner, enjoying the always exhilarating sensation of being suspended in space without support — for my friend had drawn the covering from the floor of clear glass in the car, which was coming into use in some of the new machines — when there was a terrific report. The motor had exploded!

We looked at each other in horror. This indeed was what made air-travelling far-and-away the most exciting of sports. Human beings had not yet come to regard with indifference accidents which occurred in mid-air.

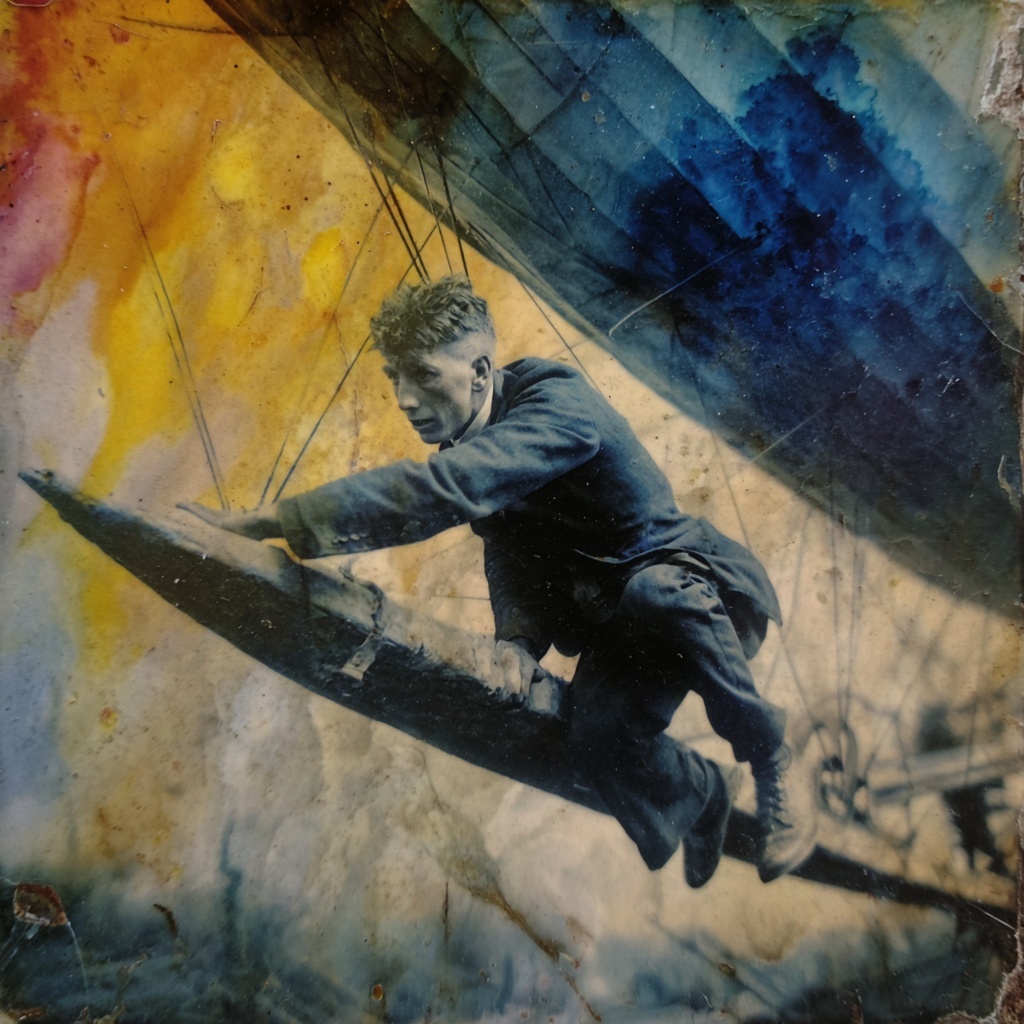

My friend picked his way through a tangled mass of machinery to the instruments. We were rising rapidly and the apparatus for opening the valve of the balloon was broken. Without saying a word, he started to climb up the tangle of wire ropes to the valve itself; a very dangerous proceeding, because many of the ropes were loosened from their fastenings. We suddenly encountered a current of air that changed our course directly east. (We had been steering south and had gone about six hundred miles.) It drew us up higher and higher. I glanced through the floor but the earth was almost indistinguishable, and was disappearing rapidly. There was absolutely nothing that I could do. I looked up again at my friend, who was clambering up rather clumsily, I remember thinking at the moment. The tangle of ropes and wires looked like a great grape vine. Just then the big ship gave a lurch. He slipped and pitched forward, holding on by one hand. Involuntarily, I closed my eyes for a moment. When I opened them again, he was gone!

My feelings were indescribable. I commenced to lose consciousness, owing to the altitude and the ship was ascending more rapidly every moment.

Finally I became as one dead.

CHAPTER II

TO EARTH AGAIN — ONE HUNDRED YEARS LATER

One day an archaic-looking flying machine, a curiosity, settled from aërial heights on to the lawn of one Dr. Newell, of Phœnix, Georgia.

When found I was unconscious and even after I had revived I could tell nothing of my whereabouts, as to whither I was going, or whence I had come; I was simply there, “a stranger in a strange land,” without being able to account for anything.

I noticed however that the people were not those I had formerly left or that I expected to see. I was bewildered — my brain was in a whirl — I lapsed again into a trance-like state.

When I regained my full consciousness I found myself comfortably ensconced in a bed in an airy room apparently in the home of some well-to-do person. The furniture and decorations in the room were of a fashion I had never seen before, and the odd-looking books in the bookcase near the bed were written by authors whose names I did not know. I seemed to have awakened from a dream, a dream that had gone from me, but that had changed my life.

Looking around in the room, I found that I was the only occupant. I resolved to get up and test the matter. I might still be dreaming. I arose, dressed myself — my suit case lay on a table, just as I had packed it — and hurriedly went downstairs, wondering if I were a somnambulist and thinking I had better be careful lest I fall and injure myself. I heard voices and attempted to speak and found my voice unlike any of those I heard in the house. I was just passing out of the front door, intending to walk around on the large veranda that extended on both sides of the house, when I came face to face with a very attractive young lady who I subsequently learned was the niece of my host and an expert trained nurse. She had taken charge of me ever since my unexpected arrival on her uncle’s lawn.

She explained that she had been nursing me and seemed very much mortified that I should have come to consciousness at a moment when she was not present, and have gotten out of the room and downstairs before she knew it. I could see chagrin in her countenance and to reassure her I said, “You needn’t worry about your bird’s leaving the cage, he shall not fly away, for in the first place he is quite unable to, and in the second place why should he flee from congenial company?”

“I am glad you are growing better,” she said, “and I am sure we are all very much interested in your speedy recovery, Mr. — What shall I call you?” she said hesitatingly.

I attempted to tell her my name, but I could get no further than, “My name is —” I did not know my own name!

She saw my embarrassment and said, “O, never mind the name, I’ll let you be my anonymous friend. Tell me where you got that very old flying machine?”

Of course I knew, but I could not tell her. My memory on this point had failed me also. She then remarked further that papers found in my pocket indicated that a Mr. Gilbert Twitchell had been appointed to a position as teacher in a Missionary School in the town of Ebenezer, Georgia, in the year 1906, and inquired if these “old papers” would help me in locating my friends. She left me for a moment and returned with several papers, a diary and a large envelope containing a certificate of appointment to said school.

She stated that inquiry had already been made and that “old records” showed that a person by the name of Twitchell had been appointed in 1906, according to the reading of the certificate, and that while en route to his prospective field of labor in an air-ship he was supposed to have come to an untimely death, as nothing had been seen or heard of him since. Further than that the official records did not go.

“Now, we should be very glad to have you tell us how you came by that certificate,” she suggested.

I was aghast. I was afraid to talk to her or to look about me. And the more fully I came to myself the more I felt that I did not dare to ask a question. The shock of one answer might kill me.

I summoned all my strength, and spoke hurriedly, more to prevent her speaking again than to say anything.

“Perhaps I can tell you something later on,” I said hoarsely. “I find my memory quite cloudy, in fact, I seem to be dreaming.”

She saw my misery and suggested that I go into “the room used to cure nervousness” and that I remain as long as possible. I passed stupidly through the door she held open for me and had hardly sat down before I felt soothed. The only color visible was violet, — walls, ceiling, furniture, carpet, all violet of different shades. An artificial light of the same color filled the room. And the air! — What was there in it?

A desk was at the other end of the large apartment. As my eyes roved about the strange looking place I saw on it an ordinary calendar pad, the only thing in the room that closely resembled objects I had seen before. The moment that I realized what it was I felt as though I was about to have a nervous chill. I dared not look at it, even from that distance. But the delicious air, the strength-giving light revived me in spite of myself. For full five minutes I sat there, staring, before starting over to look at it; for though I knew not who I was, and though I had passed through only two rooms of the house, and had met only one person, I had divined the truth a thousand times.

As I slowly neared it I saw the day of the month, the twenty-fourth. Nearer and nearer I came, finally closing my eyes as the date of the year in the corner became almost legible — just as I had done in the car of the air-ship, that awful moment. I moved a little nearer. I could read it now! I opened my eyes and glanced, then wildly tore the pads apart, to see if they were all alike — and fell to the floor once more.

It was the year two thousand and six, just one hundred years from the date of my appointment to the position of a teacher in the South!

In a short time I regained complete consciousness, and under the influence of that wonderful room became almost myself again. I learned that I had not really been left alone but had been observed, through a device for that purpose, by both the doctor and his niece, and on her return I related my whole story to her as far as I could then remember it.

The strangest and most unaccountable part was that though I had been away from the earth about one hundred years, yet, here I was back again still a young man, showing no traces of age and I had lived a hundred years. This was afterward accounted for by the theory that at certain aerial heights the atmosphere is of such a character that no physical changes take place in bodies permitted to enter it.

The physical wants of my body seemed to have been suspended, and animation arrested until the zone of atmosphere immediately surrounding the earth was reached again, when gradually life and consciousness returned.

I have no recollection of anything that transpired after I lost consciousness and the most I can say of it all is that the experience was that of one going to sleep at one end of his journey and waking up at his destination.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.