10 Best Adventures of 1974

By:

November 16, 2019

Forty-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Seventies (1974–1983) Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Robert Stone’s war/crime adventure Dog Soldiers. An extraordinary genre mashup that brings the Vietnam War home to a curdling California counterculture. When John Converse, a burned-out war correspondent, persuades his ex-Marine Corps buddy, Ray Hicks, to smuggle a backpack full of heroin back to the United States, the two frenemies (and Converse’s thrill-seeking wife, Marge) soon discover that they’ve been manipulated by a violent drug cartel. A hard-bitten tough guy who’s spent time in a cult-like desert commune rubbing elbows with freaks and free spirits, Hicks is an extraordinary figure; Stone based the character, in part, on Neal Cassady — whom the author met when he used to hang out with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. (Converse is a semi-autobiographical character; Stone was a Vietnam War correspondent.) When Hicks discovers that he’s being tailed, he goes on the lam — taking Marge as insurance. Along the way, they become lovers; Marge, meanwhile, develops a heroin habit. There are no good guys in this sordid tale: the law enforcement officer on Hicks’s trail is also on the take. when the hapless Converse returns to his abandoned Berkeley apartment, he’s tortured by sadistic goons and forced to lead his captors to Hicks’s hideaway — the remnants of the Kesey-like commune, whose freaky caves, tunnels, and psychedelic light-sound set-up makes for an atmospheric backdrop when the shit finally hits the fan! Fun facts: Dog Soldiers, which has been called one of the best English-language novels of the twentieth century, was awarded the National Book Award for Fiction. It was adapted as a 1978 movie by Karel Reisz, starring Michael Moriarty as Converse and Nick Nolte as Hicks.

- Donald E. Westlake’s Dortmunder crime adventure Jimmy the Kid. In 1960, the four-year-old son of Roland Peugeot, of the French automobile family, was snatched from a playground in a Paris suburb; the kidnappers got the idea from a translation of Lionel White’s 1953 crime novel The Snatchers. Some years later, Westlake was approached about writing a movie treatment inspired by this true crime; instead, he ended up writing a novel in which lovable loser John Dortmunder and his gang — about whom Westlake had previously written The Hot Rock (1970) and Bank Shot (1972) — base their plans to kidnap a 12-year-old on Child Heist, a fictitious Parker novel by Richard Stark — that is, Westlake’s best-known pseudonym. It’s an amusing yarn, at first reminiscent of O. Henry’s “The Ransom of Red Chief,” though Westlake uses our familiarity with that story as misdirection. The titular Jimmy the Kid is a child genius who not only comes to sympathize with the gang, but to rescue them from the feds! Fun facts: Westlake wrote 14 novels about the escapades of John Dortmunder, including Nobody’s Perfect (1977), and Why Me? (1983). He’d originally intended The Hot Rock to feature his character Parker; however, the plot ended up being too comical, so he rewrote it with a more likable cast of characters. Jimmy the Kid was adapted by Gary Nelson in 1982; the family-friendly comedy, which starred Gary Coleman, was a flop.

- Christopher Priest’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Inverted World. Having reached the mature age of “650 miles,” Helward Mann becomes an apprentice Future Surveyor — which means that he must help choose the best route for his city, “Earth,” which appears to be an Earth colony on an alien world. The city is winched along, at about eight miles per day, along tracks that are then picked up and re-used; the city’s goal is a perhaps nonexistent “optimum” destination somewhere to the north. Many of the city’s citizens (including Helward’s wife, Victoria) are unaware that the city is mobile; a decrease in the birthrate obliges the city to capture native women from the villages they pass en route. When Helward leaves the city, he discovers how truly strange the outside world is; time itself works differently, within the city vs. outside, and to the north vs. the south. Also, he finds himself pulled southward by a mysterious, ever-increasing force. Eventually, he meets a woman who claims to have come from England recently; in fact, she claims that they’re on Earth! What is actually going on? Fun facts: Expanded from a short story by the same title included in New Writings in SF 22 (1973). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction calls Inverted World “one of the two or three most impressive pure-sf novels produced in the United Kingdom since World War II.”

- Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising YA fantasy adventure Greenwitch. In the third, and possibly best installment in Cooper’s series about British children who find themselves involved in thwarting the rising of the Dark, Simon, Jane, and Barney Drew — whom we’ve previously met, in the mystery novel Over Sea, Under Stone (1965) — arrive in Trewissick (a fictional Cornwall fishing village) for a holiday. Their family friend Merriman Lyon introduces them to Will Stanton, a boy their age whom they at first dislike; he’s preternaturally composed and mature. (Readers of the second series installment, The Dark Is Rising (1973), know that Merriman and Will are Old Ones — wizards who’ve faced the growing menace of supernatural evil since King Arthur’s time.) There’s an ominous Wicker Man vibe to this story, the plot of which centers around an annual rite wherein Trewissick’s women weave a figure of leaves and branches, then cast it into the sea for good luck in fishing and harvest. As we’ve learned from the first installments in the series, the forces of Dark and Light alike must negotiate Old Magic, Wild Magic, and High Magic — eldritch forces beyond good and evil; the titular Greenwitch, who comes into possession of an artifact sought by the agents of Light and Dark alike, cannot be forced to release it… only cajoled and persuaded, by an empathetic mortal… which is where Jane Drew plays a key role. There’s a voyage beneath the sea, a ghostly ship, a creepy interlude with a sinister painter who lives in a caravan, even a dog-napping — all integrated with sophisticated mythopoeic tropes, and all serving the series’ complex larger plot. Fun facts: As a child, Cooper used to holiday in the village of Mevagissey — which inspired the setting for Over Sea, Under Stone and Greenwitch. Wes Anderson is a fan of the Dark is Rising series; let’s hope that he decides to adapt the books as a series of movies.

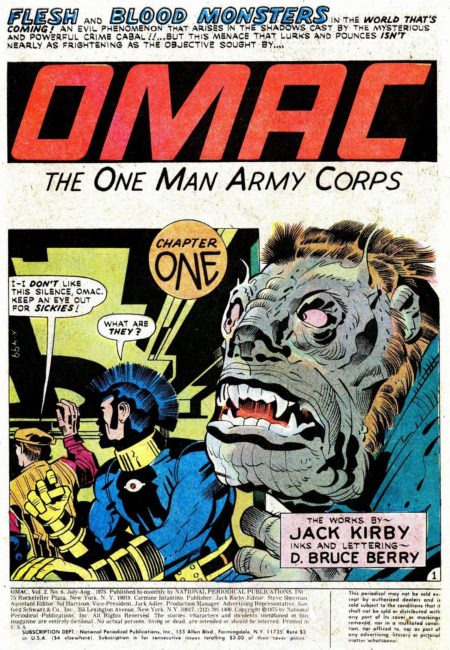

- Jack Kirby‘s New Wave sci-fi comic OMAC. While working at Marvel in 1964, Jack Kirby helped resurrect Captain America, whom he’d co-created in 1940, for The Avengers; soon, Kirby was drawing stories about the character in Tales of Suspense. Around the time that title was renamed Captain America Kirby got the idea for a far-future version of the star-spangled hero … which he brought with him when he left for DC in 1970. OMAC — the One-Man Army Corps — is a project of NASA’s and the global peace agency, agents of which conceal their national origins and ethnic identities in order to represent all humankind. Professor Forest programs an ultra-powerful satellite to remotely perform “a computer hormone operation” on the nebbishy Buddy Blank, transforming him — without his consent or knowledge — into a violently effective force for good. Alas, there were only eight issues of OMAC. In the first, our mohawked hero busts up an exploding fembot operation, then heads off to meet with his creator in Electric City. But this, he discovers, is “the era of the SUPER-RICH! When money, like technology, reaches complex proportions, complex situations arise.” Later, OMAC is sent to apprehend Marshal Kafka, an Eastern European warlord who’s developed an octopoid “multi-killer” reminiscent of Kirby’s monsters — Groot, Grottu, Fin Fang Foom — of the late ’50s. In one of his final adventures, a Get Out-like yarn about old people transplanting their brains into young bodies, OMAC picks up a Bucky Barnes-esque sidekick, albeit one so sociopathic he’s willing to sell his own girlfriend to these creeps. Fun facts: The character OMAC has popped up now and again, in DC comics over the years. Most recently, in the Infinite Crisis storyline, OMACs were portrayed as humans whose bodies have been corrupted by a nano-virus. The acronym has been reinterpreted to mean “Observational Meta-human Activity Construct” and “Omni Mind And Community.”

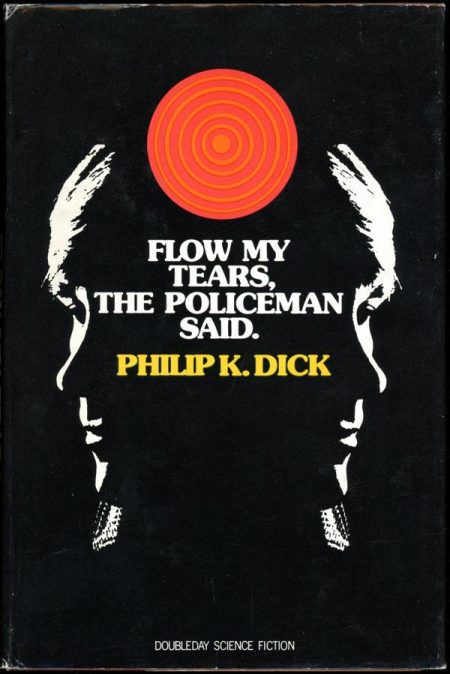

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said. A typically dystopian, disorienting, and dashed-off Philip K. Dick joint — but one which is more emotionally resonant than his Fifties and Sixties oeuvre; in this sense, Flow My Tears points the way forward to Dick’s late masterpieces, A Scanner Darkly (1977) and VALIS (1981). The year is 1988; in the aftermath of a Civil War, the USA has become a police state; African-Americans have been all but exterminated; college students have become underground guerrillas; people use their smartphones to seek hook-ups (via the Phone-Grid Transex Network) and advice (via Cheerful Charlie, an app); and recreational drug use has been normalized. When a crazed ex-lover sics a “gelatinlike Callisto cuddle sponge” on Jason Taverner, the famous pop star (“Nowhere Nuthin’ Fuck-up” is his latest hit) and TV host wakes up in a motel to discover that… no one knows who he is. Taverner takes drugs, seeks assistance from a series of women — an unstable old flame; a leather-clad lesbian; a sweet-tempered potter — and desperately attempts to figure out what might have caused him to become a non-person. The titular policeman? He’s the twin brother and lover of the leather-clad lesbian, and a powerful authority figure who learns an important lesson in humility and empathy for others. Fun facts: Winner of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 1975. Dick would later parody this novel, in VALIS, as The Android Cried Me a River.

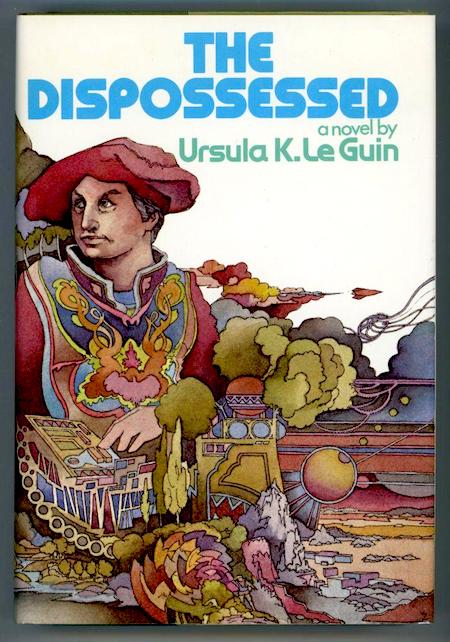

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Dispossessed. Shevek, a brilliant young physicist, lives on the peaceful anarchistic planet Anarres, whose inhabitants value voluntary cooperation, local control, and mutual tolerance. This is a richly imagined world — with a language, for example, that cannot readily express “propertarian” or “egoist” concepts. The downside of this utopia is an entrenched bureaucracy that stifles innovation, particularly if it seems to challenge the prevailing political and social ethos. Shevek’s new temporal theory, and the resulting “Ansible” that he hopes to develop (which will allow instantaneous communication between any two points, no matter how many light-years apart; and which will therefore make possible a galactic network of civilizations), may never see the light of day. So he relocates to Urras, a nearby world (Annares is its moon) where disruptive new theories and technologies are welcomed. Once there, however, Shevek is dismayed and disgusted by Urras’s two largest states: the USA-like A-Io, which is capitalist, sexist, wasteful, exploitative, and tumultuous — forever on the verge of revolution or war; and the authoritarian, USSR-like Thu. While the author is clearly sympathetic to the ideals of Annares, The Dispossessed is a pointed critique of typical utopian narratives; the dichotomies that Le Guin describes are not readily surmounted — it’s a negative-dialectical romance. Fun facts: Although this was the fifth novel published in Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle, chronologically it is the first. The Dispossessed won the Nebula and Hugo Awards for Best Novel. Later editions of the book are subtitled “An Ambiguous Utopia.”

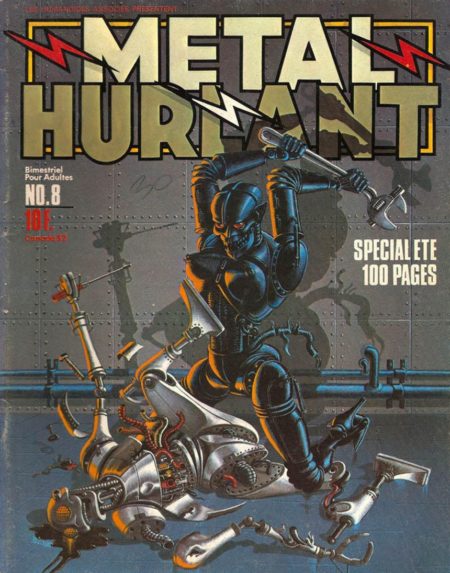

- The Humanoïdes’ magazine of New Wave sci-fi and fantasy comics Métal hurlant. In 1974, Jean Giraud, the French cartoonist who’d brought a gritty realism to cowboy comics with Blueberry, the popular strip he and writer Jean-Michel Charlier contributed, from 1963–1974, to Pilote, and who’d recently attempted to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune with Alejandro Jodorowsky, while simultaneously beginning to write and draw experimental, trippy sci-fi and fantasy comics under the nom de plume Moebius, co-founded the comics art group and publishing house Les Humanoïdes Associés. The comics writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet, comics artist Philippe Druillet, and businessman Bernard Farkas were the other “Humanoïdes”; in December of that year, the four visionaries began publishing the magazine Métal Hurlant (Howling Metal), which would revolutionize Franco-Belgian comics. Here was a comics magazine for adults: cinematic, surreal, erotic, complex. Moebius’s “Arzach” stories, about a silent warrior riding a pterodactyl-like creature through a desolate dreamscape, appeared in 1974–1975; his non-linear serial The Airtight Garage appeared from 1976–1979; and his famous L’Incal series, co-created with Jodorowsky, began to appear in 1980. Other contributors included: Druillet, Richard Corben, Enki Bilal, Caza, Serge Clerc, Alain Voss, Berni Wrightson, Milo Manara, Frank Margerin, Masse, and Chantal Montellier. The magazine, which ceased publication in 1982, exercised a profound influence upon everyone from Ridley Scott and Hayao Miyazaki to William Gibson, Mike Mignola, and Neil Gaiman. Fun facts: The magazine Heavy Metal, which translated Métal hurlant for an English-speaking audience, was published in the United States — beginning in 1977 — under the National Lampoon umbrella.

- William Goldman’s political thriller Marathon Man. When two old men get into a fender-bender in New York, Dr. Szell, a sadistic former dentist at Auschwitz, is forced out of hiding in Paraguay — because he no longer has any way to convert the diamonds he stole from Jewish prisoners into cash. Szell’s ill-gotten gains have been funneled through a secret US agency, “the Division,” to whom Szell has passed information about other escaped Nazis. Szell’s Division contact, Hank “Doc” Levy, is a tough op masquerading as an oil company exec; Doc’s younger brother, Tom “Babe” Levy, is a Columbia grad student and avid runner. When Szell travels to New York, he decides that Doc is planning to rob him; and he winds up abducting Babe, in an effort to extract information — via a nightmarish dental procedure — about the supposed heist. Babe is no secret agent, but thanks to his training as a marathoner, he’s able to escape… and then he seeks revenge. A cynical, violent thriller for the beginning of a cynical, violent era; Goldman’s black humor and vivid writing redeem what otherwise might be a sordid, sick, depressing story. Fun facts: Goldman, who won Academy Awards for his Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and All the President’s Men (1976) screenplays, also wrote The Princess Bride (1973) and its screenplay. John Schlesinger adapted Marathon Man in 1976; the movie stars Dustin Hoffman, Laurence Olivier, and Roy Scheider. “True, this thriller is hardly fast-paced, soaks its story in patient period detail, and reveals its plot points only when necessary,” writes Gordon Dahlquist. “Yet such is the confidence of the whole thing that your attention never flags — a confidence exactly balanced between Schlesinger’s artistic taste and writer William Goldman’s pulp acuity.” Goldman’s final novel, Brothers (1986), is a gimmicky, far-fetched sequel to Marathon Man.

- John le Carré’s Karla Trilogy espionage adventure Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. David Cornwell, who wrote under the pseudonym John le Carré, worked as a British intelligence officer during the early Cold War; Kim Philby’s defection to the USSR, and the consequent compromising of British agents, was a factor in Cornwell’s return to private life. So it’s only fitting that in his first outing, 1961’s Call for the Dead, the un-James Bond-like George Smiley should be an ex-operative who roots out an East German spy ring operating in the UK. In 1963’s The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, Smiley returns to the Circus (that is, the secret intelligence service) as top aide to its head, Control. As this novel begins, Control and Smiley have been forced into retirement after “Testify,” an operation in Czechoslovakia, ends disastrously. Smiley discovers that there is a Soviet mole operating at the highest level within the Circus — that is to say, it must be someone he’s known and trusted for years. But who? With the assistance of an increasingly paranoid Peter Guillam, his former protégé and right-hand man, Smiley investigates four ambitious senior Circus men: Alleline, the new Circus chief; Haydon, commander of London Station (and Smiley’s wife’s lover); Bland, Haydon’s lieutenant; and Esterhase, who is in charge of surveillance and wiretapping for the Circus. He discovers that two major Circus operations — the ill-fated “Testify,” and also “Merlin,” a highly successful intelligence-gathering operation led by Alleline and the others — are not at all what they seem. Karla, Moscow Centre’s spymaster, seems to have been been manipulating the Circus — and Smiley — for years. If this is true, how will Smiley flush out the mole? Fun facts: Considered one of Le Carré’s best books, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy was adapted as an excellent movie — starring Gary Oldman as Smiley, along with Colin Firth, Tom Hardy, John Hurt, Toby Jones, Mark Strong, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Ciarán Hinds — in 2011. It was previously adapted into a BBC TV miniseries in 1979, with Alec Guinness in the lead role. The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and Smiley’s People (1979) are the subsequent installments in Le Carré’s so-called Karla Trilogy.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.