Listen, Hollywood! (10)

By:

October 19, 2019

One in a series of 10 posts suggesting novels (from Josh Glenn’s BEST ADVENTURES series) that really ought to be adapted for the big screen.

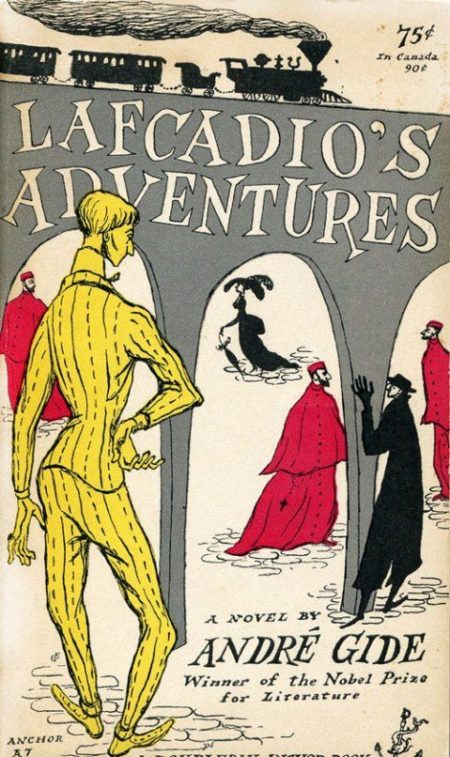

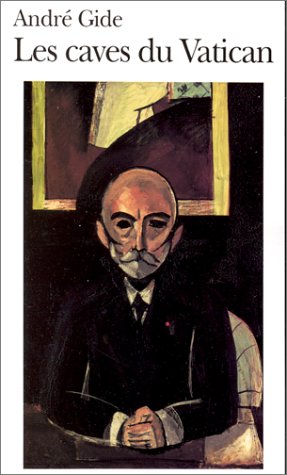

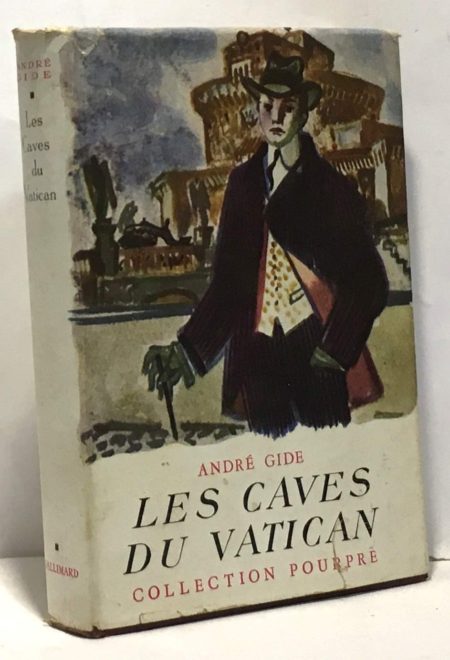

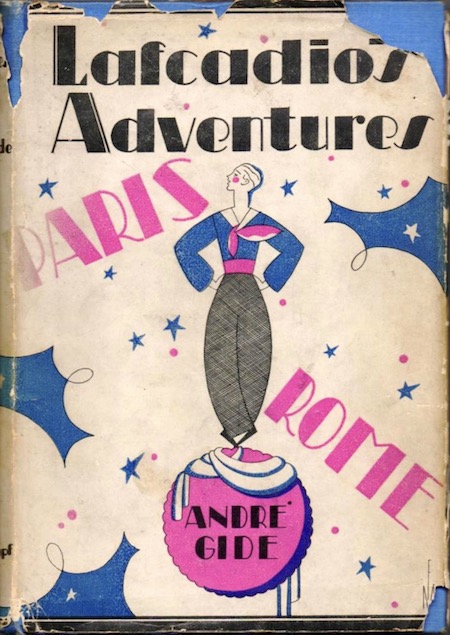

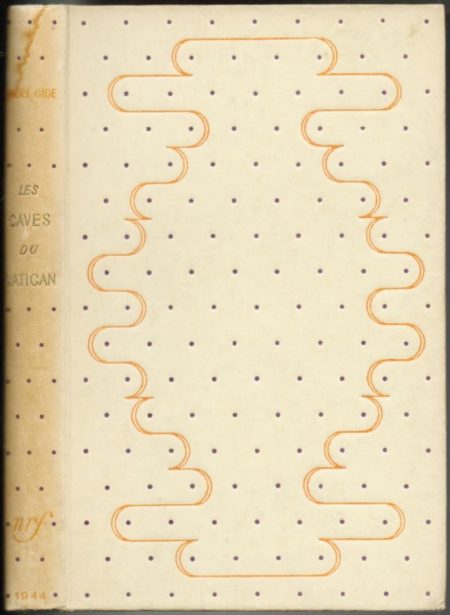

André Gide‘s Les caves du Vatican (in English: Lafcadio’s Adventures, The Vatican Catacombs, The Vatican Cellars) appeared on my list of the Best Adventures of 1914.

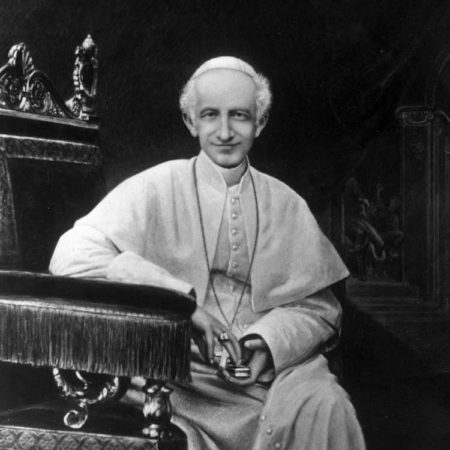

After defeating the papal army in 1860, Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia seized all papal territories except Rome, and took the title King of Italy; when he seized Rome in 1870, he completed the process of consolidating the Italian peninsula’s various different states into the Kingdom of Italy. Pope Pius IX denounced this new state as an illegitimate creation of revolution; refusing to leave Vatican City ever again, he declared himself a “prisoner of the Vatican.” His successor, Leo XIII (Pope from 1878–1903), followed suit. Midway through Leo XIII’s reign, a conspiracy theory, to the effect that the Pope had been replaced by a Masonic impersonator, swept Europe. A gang of con artists took advantage of this ridiculous rumor by posing as clergymen — on a crusade to rescue the true Pope from the Vatican cellars — and fleecing innumerable pious, wealthy Catholics.

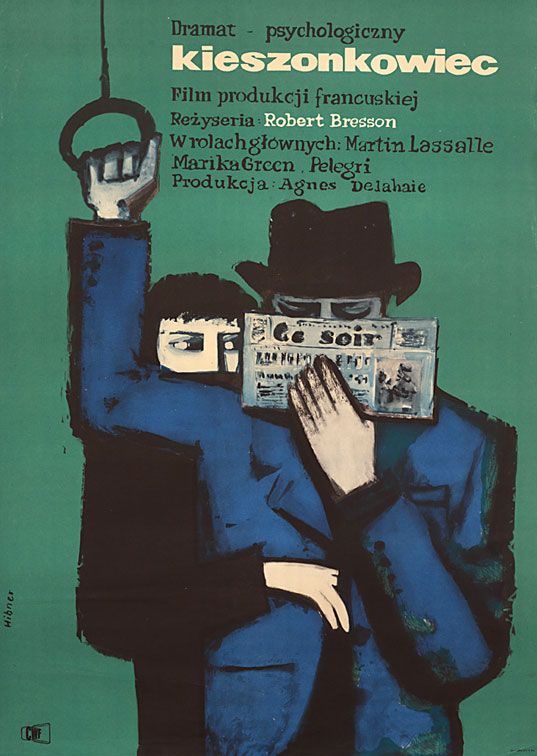

Gide, a Protestant-born atheist, was amused by this (true) story; he set his satirical picaresque, Les caves du Vatican, in this milieu. It’s an excellent novel, which Gide rendered unfilmable as follows: our protagonist barely appears; his adventures are mostly described rather than shown, recounted in the past tense; pederasty is hinted at (Gide’s own erotic impulses were directed toward adolescent boys); the female characters aren’t given much to do; and our hero, despite his charms, commits a truly sociopathic act. (Also, it’s way too complex: Take a look at the wildly divergent cover illustrations, below.) However, in this, the final installment of the LISTEN, HOLLYWOOD! series, I will do my best to make a case for why and how this great, troubling story might be adapted.

Elevator pitch:

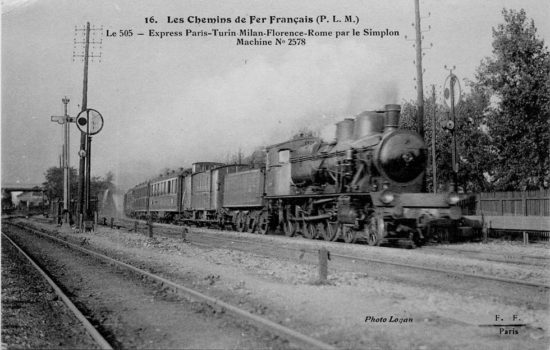

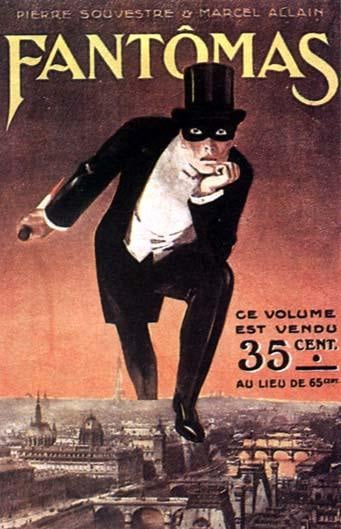

Lafcadio, a sexy, streetwise, 19-year-old dandy and hustler, is one of the most compelling antiheroes of French literature. Like Arsène Lupin and Fantômas — the criminal exploits of whom were admired by French artists and authors such as Queneau, Cendrars, Magritte, Desnos, and Apollinaire — Lafcadio swings past right and wrong, obeying only his own code of conduct. Trained for adventure since childhood, he finds himself caught up in an old friend’s con game, the victims of which are members of his own family, whom he’s just rediscovered. The action jumps from Bucharest to Paris, to Rome and Naples; there are beautiful girls, a burning building, con men and women, a master of disguise, a violent scene aboard a speeding train, and a youthful romance. It’s The Sting + Mission Impossible + Breathless. Taika Waititi, Guy Ritchie, Wes Anderson: listen up, this is a comedic thriller right up your alley.

First act:

In the first act, we meet our principal players and learn what makes them tick. It’s a dramedy about social status, religious sentiment (whether truly pious or self-serving), and bourgeois self-esteem — disrupted by an extraordinary character to whom none of these things are at all important.

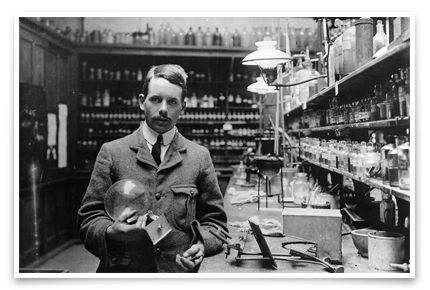

The story begins in Paris of the Belle Époque — an era of peace, prosperity, and an ongoing culture war between pious Roman Catholics and progressive types who place their faith instead in scientific and technological innovation. We are introduced to the Péterat sisters: the shallow, social-climbing Marguerite; the long-suffering Veronica; and the foolish Arnica. Twenty years earlier, Marguerite made a brilliant marriage to Julius de Baraglioul, esteemed novelist and son of the highly decorated diplomat Count Juste-Agénor de Baraglioul; their 19-year-old daughter Genevieve is beautiful and compassionate, while their young daughter Julie is adorable. Veronica married Anthime Armand-Dubois, a scientist who experiments on rodents (in search of the secret of the “tropisms” governing all organic matter), and an outspoken atheist. Arnica married Amédée Fleurissoire, an awkward, naive, but good-hearted small-town businessman who has found modest success producing kitschy religious statuary.

Gide is lashing out in all directions, here:

- Like status-obsessed women in an Austen or Thackeray novel, the Péterat sisters are figures of fun; in fact, their name can be translated as something like “Fartwell.” None of them are particularly intelligent.

- Julius is a middlebrow novelist concerned only with his reputation. He prides himself on having led a blameless life, but Gide describes his as an “invertebrate career.” Julius’s elegant but anodyne novels reflect his inner vacuousness; his newly published work, a thinly fictionalized account of his father’s diplomatic career, is particularly dull. Although not a particularly devout Catholic, he cannot afford to appear as anything else because his sister, Valentine, is working her wiles on Cardinal André, an influential member of the Académie française, in order to advance Julius’s career.

- Anthime is a figure whom we might compare to Richard Dawkins or Daniel Dennett — an outspoken atheist who argues that empirical science is the only basis for genuine knowledge of the world, and who insists that a belief can be epistemically justified only if it is based on adequate evidence. He is an arch-inductionist, oppressive in his righteousness and destructive in his negativity. He is unkind to his wife; his experiments are cruel to animals. He is a prominent Mason, and relies on the Lodge for financial assistance; like Julius, that is, his faith is entangled with material considerations.

- Amédée, whom we don’t meet until fairly late in the book, is one of God’s innocents. When Arnica jilted his close friend, the equally ridiculous Gaston Blafaphas, and married him, Amédée felt so guilty that he promised never to consummate the marriage — so he remains a virgin. Amédée is truly pious and devout; his faith has never been tested. Although he has found some success in the religious kitsch business, he longs to embark on a noble crusade. The Fleurissoires reside in Pau (in southern France); coincidentally, Julius’s sister, Valentine, has retired to an elegant country residence nearby.

It seems to me that Gide is poking fun at various aspects of himself, via these characters. Like Julius, he is a novelist who pretends that fame and fortune mean nothing to him, when in fact they are his obsession; like Anthime, he is an outspoken atheist motivated by a perhaps absurd sense of moral concern and even outrage about the effects of religious belief on the populace; and like Amédée, as he would confess in his 1952 memoir Madeleine (et Nunc Manet In Te), Gide was embroiled for years in an unconsummated marriage. And our bisexual, amoral titular character, is of course Gide, too: he is perhaps the author’s ideal avatar.

At any rate, the movie should start out in the vein of, say, La Gloire de mon père. Like Marcel’s father, an atheistic school teacher, and his Roman Catholic Uncle Jules, in Yves Robert’s charming French movie, Gide’s story begins with argumentation between Anthime and Julius.

Anthime is afflicted with painful rheumatism; he can barely walk without a crutch. (We see him working in his home laboratory — it amuses Gide to describe Anthime’s complicated system of rat mazes as an effort to “wring from the helpless animal the acknowledgement of its own simplicity” — stubbornly bearing up under duress.) He and Veronica have relocated from Paris to Rome, in order to consult a specialist in rheumatic complaints. Their new apartment features a built-in Virgin Mary statue, to which Veronica secretly prays for her husband.

The Baragliouls have come to pay the Armand-Dubois family a visit. We learn that Julius’s father, the highly decorated diplomat, is now on his deathbed. Anthime insults Julius’s new book; this is a running joke, as Julius can’t find anyone to compliment the book — not his wife, not even his own father. The book glorifies “the dignified, the ordered, the classic calm of Juste-Agénor’s existence in its twofold aspect, political and domestic,” doing so as a rebuke to the “turbulent follies of romanticism.” But this is dull, insipid stuff. ALso, Julius’s father’s life was romantic — Julius seems to be the only one who doesn’t know it.

Gide draws a humorous contrast between the sisters Marguerite and Veronica. Julius’s wife is built for martyrdom: “With all her might [she] yearned to suffer. Life unfortunately offered her little to complain of.” Veronica, meanwhile, who is patient and even-tempered, is forced to put up with the obstreperous Anthime, who is violent in his denunciation of her faith.

In the course of the dinner conversation, perhaps we hear the rumor making the rounds — about the abduction of the Pope, and his replacement by an imposter.

The Baragliouls urge Anthime to go to church and pray for relief from his rheumatism; enraged, he insists that he’d refuse even if God offered him a miracle. When his wife confesses that she’s been lighting candles for him in front of their apartment’s statue of the Madonna, he hobbles off and hurls his crutch at it — hoping to break the candle, but he breaks off one of her hands. That night, he has a vivid dream about the Virgin Mary appearing to him — and when he wakes up, his rheumatism is gone. It’s a miracle!

Overnight, Anthime becomes the most devout, even saintly member of the family. He ceases his animal experiments, he stops writing anti-religious editorials for newspapers, and — at the urging of the Catholic church — he publicly denounces the Masons. Of course, he is now plunged into abject poverty. But he doesn’t care: He is like Saint Francis, entirely devoted to the glory of God.

Back in Paris, Julius goes to visit his father — who also mocks his novel. As he nears death, Count Juste-Agénor wants to get something off his conscience. So he admits to Julius — not in so many words — that he has an illegitimate son named Lafcadio Wluiki (pronounced Louki), who is a 19-year-old Romanian living in Paris. This comes as a stunning surprise to the milquetoast Julius, who’d believed that his father was an utterly upright, moral person. As we’ll see, Julius now begins to go through a midlife crisis: “For the first time in his life awful questionings beset him.” He feels like a fraud.

In this unstable frame of mind, Julius travels to a seedy part of town to find Lafcadio. His illegitimate half-brother isn’t home, but he’s shown into his apartment by Lafcadio’s mistress, the attractive Italian Carola Venitequa. Carola is a good-hearted guttersnipe, who does whatever it takes to survive; she’s like Nancy, in Oliver Twist — not respectable, but not evil. In fact, Gide was a Dickens fan; I think Carola must be an homage to the character of Nancy.

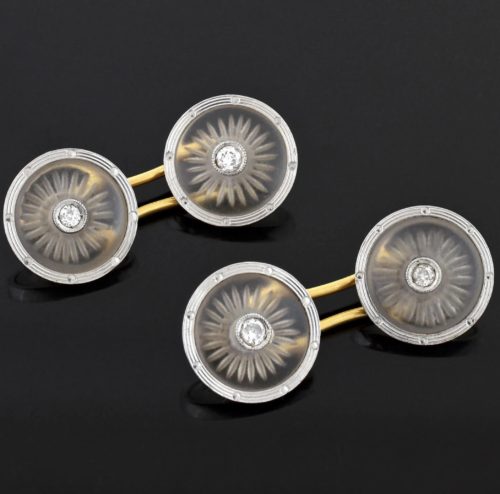

Carola’s bohemian affectation is wearing a man’s shirt, complete with cuffs and cufflinks. (Gide doesn’t give Carola much to do, but she’s a potentially terrific character — the movie adaptation could do much more with her, I think.)

Julius snoops around, and discovers that Lafcadio possesses only a few cheap adventure novels — Robinson Crusoe, The Arabian Nights, Oliver Twist — in English, Italian, and French. He also discovers a snapshot of Lafcadio, at 15, naked on a beach with his (clothed) mother and her lover; and a diary in which Lafcadio chronicles his efforts to become “slim,” which means, in schoolboy slang: a superior type who never allows anyone to perceive his unique abilities.

Lafcadio believes that the “slim” are a secret society of superior types. They are highly differentiated and unique, no two are alike. Opposed to them are the “crusted,” a great mass of people — whether rich or poor — who are inferior. He and his schoolmate Protos agreed that “1) The slim recognize each other. 2) The crusted do not recognize the slim.” They both aspire to join the ranks of the slim.

For the purposes of the movie adaptation, we’d want to show Lafcadio being “slim,” rather than having the audience learn about through a diary voiceover. So let’s move an action sequence from later in the story to earlier in the movie — let’s show Lafcadio acting heroically, and then furious at himself for showing off.

Lafcadio is walking through Paris, looking elegant but raffish — his clothes well-worn, but his bearing aristocratic and insouciant. He comes across a burning house. The woman of the house is screaming hysterically — her children are trapped on the second floor. A lovely young woman — Lafcadio’s age, but clearly upper-class — is offering the contents of her purse to any man who will save the children. Lafcadio drops his walking stick and coat at her feet, swarms up a drainpipe and makes some athletic maneuvers — this is the sort of thing he’s trained himself for, though it’s more likely that he’d use these skills to burgle a house than save children — and smashes through a window. Flames and smoke billow out — surely he’s dead. But then he appears, triumphantly, and lowers the children to the ground via knotted-together sheets.

He returns to the pavement, and when the young woman hands him her purse, he pours the money into the relieved mother’s hands, and lets the young woman know that he’d like to keep her purse as a memento. He kisses the purse, before pocketing it — very suave. He’s surrounded by admiring people, shaking his hand and pounding him on the back, when his mood suddenly changes — he’s just remembered his resolve not to let anyone recognize his superior abilities and character. Almost snarling, he shoves his way through the crowd and disappears. The young woman — later, we’ll discover that this is Genevieve, daughter of Julius and Marguerite — watches him go with wide eyes. She’s speechless, flustered; this handsome young man looks poor, but behaves like a noble.

Who is Lafcadio? He was born in Bucharest in 1874, to a beautiful Romanian woman; he never knew his father. Instead, from a young age he has been influenced by a series of “uncles” — his mother’s exotic, foreign, brilliant, wealthy lovers. Think of young Bruce Wayne, training himself in all sorts of arts and physical abilities that will make him a great crimefighter and detective some day; Lafcadio, too, is receiving training to be an adventurer — although he doesn’t know it.

How do we depict Lafcadio growing up, in the movie? Perhaps when Julius pries into Lafcadio’s diary, there’s an extended flashback where we see a young man grow up from a child to a young adult. He and his mother travel around Europe; she is a saloniste, hosting brilliant parties. His “uncles” include a German financier who teaches him German, how to calculate exchange rates, and how to do complex sums in his head. Another “uncle” is Prince Wladimir Bielkowski, who teaches him Polish; Ardengo Baldi teaches him Italian, and how to play chess so well that he doesn’t have to look at the board. Baldi is also a juggler, conjurer, mountebank, acrobat — he teaches Lafcadio circus tricks, how to cheat at cards. His “uncle” the Marquis de Gesvres takes him to Paris and teaches him to dress beautifully; they spend entire days at the shirtmaker’s, the shoemaker’s, the tailor’s. His “uncle” Fabian Taylor, a foppish English aristocrat, teaches Lafcadio how to behave beautifully, how to appreciate fine wine and cuisine, and so forth.

There are strong hints in Gide’s novel that at least some of Lafcadio’s uncles were half in love with the boy — some in less innocent ways than others. The German, for example, encouraged Lafcadio to take naked baths in rivers and lakes every day of the year, no matter the weather. Uncle Faby — whom we see in the photograph on Lafcadio’s mantel — takes mother and son (then 15) to his villa on the Adriatic, and locks up the boy’s clothes — so that he’ll get an excellent tan, he claims. We get the impression that Lafcadio was aware of the effect that he had on his mother’s lovers, and that it amused him – perhaps flattered him. There’s also no strong suggestion that any of these man actually laid a finger on the boy, except for Faby — who takes Lafcadio on a solo trip to Algeria. (We know from Gide’s own life that it was in Algeria that he first allowed himself to have homosexual encounters — with adolescent boys.) We don’t get the sense that Lafcadio was preyed upon — he seems to have been in love with Faby, himself — and yet, of course, pederasty is reprehensible. Gide would disagree: he became an eloquent apologist for pederasty. Still, how to deal with this aspect of Gide’s book, for the purposes of making a movie for today’s audience?

At age 15 or 16, Lafcadio is sent to Paris for formal schooling. There, at his boarding school, where he’s terribly bored — because he’s already so advanced, in some ways, and so ignorant in others — he meets Protos. Protos is an older Italian boy who has decided that he will lead a life of crime. He appears to be ignorant, even stupid — but Lafcadio discovers that he’s actually brilliant, capable of being the best student in the school. But Protos firmly believes that the “slim” — the secret fraternity of superior types, who prey upon foolish wealthy types — must remain always in disguise, never allowing anyone to see what they’re really like. (“The important thing in this world was never to look like what one was.”) This charming sociopath introduces Lafcadio to this idea; he also introduces Lafcadio to his mistress and partner in crime, Carola — who will later be Lafcadio’s mistress.

PS: Protos is Greek for “first.” This is an ironic schoolboy nickname, since the boy — his real name is never revealed — was apparently very stupid. He received the nickname from his peers when — in a moment of pique — he let slip how smart he actually was, and received the highest marks in the class for a Greek recitation.

Lafcadio’s mother dies, and his uncles all vanish — so he suddenly finds himself penniless in Paris. I’m extrapolating this next bit: Protos is off in Rome working on some elaborate con; Lafcadio and Carola commit various minor crimes and cons in order to survive. (Perhaps we see Carola pointing out a distinctive pair of cufflinks, in a jewelry store’s window; these will become an important clue, later.) This has been going on for a couple of years — Lafcadio is now 19 — when Julius comes on the scene.

Lafcadio has continued to train himself, during this period. For example: “I can read writing or print with perfect fluency, upside-down, or in transparency, or in a looking-glass, or on blotting-paper — a matter of three months’ training and two years’ practice — all for the love of art.” He hates indecision; he carries with him a pair of cribbage dice, and rolls them to determine what he should do when he can’t make up his mind. He is a pickpocket, a burglar, a con artist — but he is driven not by a desire to prey upon lesser mortals (like Protos) but only by a desire to realize his own potential. He is a knight in search of a quest; setting himself challenges and punishing himself when he fails.

It’s my impression — not sure this is what Gide had in mind — that Protos sought to gain power over Lafcadio, to use him as a con man, blackmailer, etc. Later in the book, he will say to Lafcadio, “I always thought something might be made of you. With a handsome face like yours, we could have got round all the women, and for the matter of that, God forgive me! bled one or two of the men in the bargain.” Lafcadio learned a lot from Protos, and agrees with much of his worldview — but ultimately he’s not evil.

How does Lafcadio punish himself? By stabbing himself, with a penknife, in the thigh. He does so whenever he’s made the mistake of revealing his superiority. As Julius discovers from Lafcadio’s diary, he punishes himself for beating someone at chess, for allowing someone to discover that he speaks multiple languages. He also punishes himself for backsliding into bourgeois morality and sentimentality; he is his own moral arbiter. He’s learned from Protos that nothing is immoral; everything is permissible. He wants to be as amoral as Protos; but this doesn’t meant that he wants to be evil, or to lead a life of crime. What he wants is adventure. And what he demands of himself morally is that what makes him act should not be a matter of interest; he should do things, whether “good” or “evil” in a disinterested manner.

This explains why he doesn’t want to be rewarded, or even congratulated, for having saved the lives of the children from the burning building. And it also explains why he doesn’t keep any of the money that he gains from his criminal activities. He strives to be disinterested, stoic; and he is in training for some great adventure.

Although Gide doesn’t make this explicit, and perhaps wouldn’t agree with my interpretation, I get the sense that Lafcadio has spent his early adulthood attempting to live beyond good and evil — acting without any selfish or moral motives — but what this has meant, primarily, has been committing petty crimes and then not keeping the proceeds. So perhaps he’s burgled homes, pickpocketed Parisians, shoplifted, etc., etc. — and then dropped his ill-gotten gain in the trash, or into a mailbox, or even dropped it off at a police station. I’m just extrapolating, here. He’s been living life as an adventurer, but it’s all been fairly seedy — perhaps he’s a bit ashamed of the way he lives. He may long to do good deeds, too, but no opportunities have presented themselves — and perhaps he fears that doing a good deed is always motivated by a sense of morality, so he holds off. At any rate, when he meets Genevieve, he is inspired at last to do a good deed. Under her influence, he now commits only good deeds — until his final, terrible disinterested act. More on this subject, later.

Lafcadio lives like a secret agent, always watchful and wary. So when he comes into his apartment and finds Julius there he can tell immediately that Julius has read his diary — because he’d placed a tiny bit of wax on the drawer where the diary is kept, and it’s been disturbed. He’s angry with Julius, and basically throws him out; later, he stabs his thigh for (a) having allowed a stranger to read his diary, and (b) having allowed Julius to see that he was angry about it. Julius leaves his card with Lafcadio, and says something — not very convincingly — about needing a secretary.

Once Lafcadio calms down, he becomes curious about why this pompous successful novelist has visited him. He goes out and buys Julius’s new book, tries to read it, quickly decides that it’s terrible, and uses it as a towel to soak up rainwater on a bench where he sits. He goes to the library and looks up Julius — nothing interesting there — but then notices, in the preceding entry in Who’s Who, that Julius’s father, Juste-Agénor, the Comte de Baraglioul, was ambassador at Bucharest in 1873 — the year before Lafcadio was born.

Aha! Lafcadio goes to visit Juste-Agénor, and is permitted entry to the diplomat’s palatial home. Though dying, the old man is virile, an adventurous type — Lafcadio is much more like him than Julius will ever be. (“Julius’s features were only a vapid replica of his father’s, just as Julius’s novel was a bowdlerized and namby-pamby version of his life.”) Juste-Agénor lets Lafcadio know that he will never acknowledge him; however, he promises to increase his legacy to Julius, whom he will instruct to pass money along to Lafcadio. They have a touching scene — they embrace, tearfully. The old man gives Lafcadio some cash for new clothes.

Lafcadio goes out and buys a very distinctive pair of cufflinks for Carola (who likes to wear men’s shirts with cufflinks, as noted), and writes her a note letting her know that he’s leaving Paris to seek adventure, and will never see her again; he sends this package to her. He then takes himself to the tailor, shoemaker, etc., buying himself an elegant outfit and a handmade hat.

The next day, Lafcadio visits Julius at home — where he encounters Genevieve, who can hardly believe it’s the same young man. Julius is going through his crisis, and finds Lafcadio fascinating — he pumps him for details about his nomadic, illicit lifestyle and his philosophy of living. Lafcadio says that writing novels seems a “colorless affair” because you can revise your initial thoughts and words until they’re perfect and inoffensive, whereas in one’s life there is only action — once something is done, there’s no correcting it. Word comes that Julius’s father is dead.

In Gide’s novel, Lafcadio now leaves Paris, intent on a life of adventure. Perhaps, instead, for the movie adaptation, he takes a position as Julius’s secretary — if for no other reason than to get to know Julius’s daughter, Genevieve, better? A change like this will help the love-story aspect of the movie, while also placing Lafcadio in the right place at the right time for the violent scene on the train, in Act Three.

If Lafcadio does stay in Paris, working for Julius (and wooing Genevieve), perhaps we’d see him introduced to Julius’s world: “the set which I frequent in Paris — smart people, and literary people, and ecclesiastics and academicians.” He is no doubt admired as a kind of Parisian apache.

Second act:

In the second act, this becomes a movie about con artists on the make. It’s Catch Me If You Can, American Hustle, The Sting — except the con artists are not sympathetic characters. Protos is too sociopathic; he truly sees himself as an übermensch who has every right to prey on others. He and his gang of con artists — known collectively as the Millipede — may be ruthless, but it’s enjoyable to watch them in action.

Lafcadio drops out of the middle section of Gide’s novel. We discover, later, when he reappears, that he has been making his way slowly across Italy — before setting sail for Java. He has been enjoying his new life of leisure. He continues to live in a disinterested manner — mostly, by helping people out whenever possible. We see him tempted to commit crimes — but he never does. However, his philosophy of disinterestedness is challenged by a life that’s too goody-goody; if he doesn’t commit any crimes, then perhaps he’s just a bourgeois moralist? The pressure builds up; he feels driven to prove himself disinterested but doing something truly terrible, committing a violent but absolutely motiveless crime.

Or is Lafcadio traveling with Julius, per my note at the end of the first act? He could still commit disinterested good deeds… I also wonder if Genevieve should also be traveling with these two — she should be given more to do, in the story.

Genevieve also drops out of the middle section of Gide’s novel. When she reappears, we’re expected to believe that she and Lafcadio have fallen in love with one another. But perhaps we could give her more to do; perhaps she and Lafcadio spend some time together, before he leaves Paris? This story is, in part, a love story — but Gide doesn’t let us see it unfold. The Genevieve-Lafcadio scenes could help us understand the struggle in Lafcadio’s soul; he wants to go beyond good and evil, but under Genevieve’s influence he finds himself doing good deeds. Perhaps we see him resort to aleatory decision-making methods, when faced with the possibility of doing something “right” or “wrong” — he rolls his little cribbage dice (mentioned previously), flips a coin, or uses some other means of deciding. Whatever the result, he always acts immediately — doesn’t think about it. (This will help us understand why he behaves the way he does on the train to Naples, later on.)

Meanwhile, Protos, Carola, and Amédée are the key characters in the movie’s second act. Disguised as a handsome Italian priest (Father Salus), Protos pays a visit to Julius’s sister, Valentine, at her elegant country residence near Pau. He is such a master of disguise — there is a Mission Impossible aspect to this story — that at first, we don’t know who he is, either.

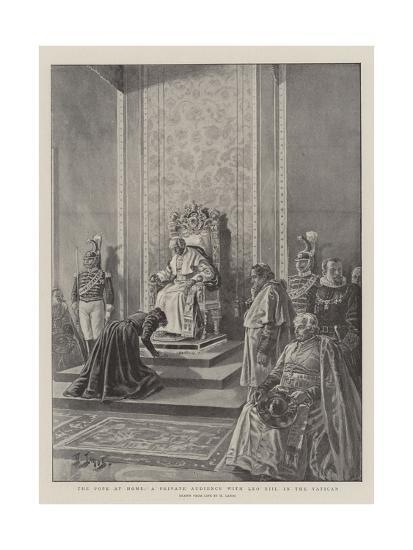

Father Salus convincingly persuades Valentine that the Lodge (that is, the Masons) and the president of Italy have installed a false Pope on the throne in the place of Leo XIII. (This is a rumor that’s been going around, for a few years; we’ve already encountered it, in the first act.) He claims that he’s a member of a secret organization within the Church, on a crusade to rescue the Pope. It’s a complex story — as with every successful con, there are answers to every question like, “Why don’t you just go to the authorities?”

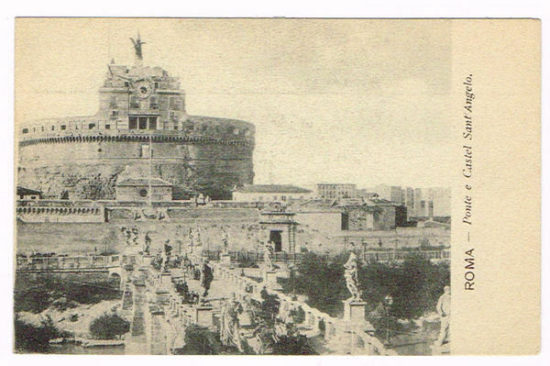

Father Salus flatters Valentine, who loves to hob-knob with cardinals, that her faith is “something more than worldly conventionality — not a mere cloak for indifference.” He points out that the Pope’s infamous encyclical to France, denying the holy cause of royalty and giving its approval to the French Republic [no doubt he refers to “Au Milieu Des Sollicitudes,” 1892], clearly couldn’t have been the work of the true Pope. He claims that the Pope is confined in the Castel Sant’Angelo (a towering cylindrical building in Parco Adriano, Rome); it communicates with the Vatican via an underground passage.

Father Salus and his confederates can’t mount a rescue mission until they’ve raised enough money to allow the Pope to leave the country and live out of the persecutors’ reach. Even those Church insiders who know the truth must pretend submission to the false Pope — lest the real Pope be murdered. Any private initiave to rescue the Pope will be met with explicit and catgeorical denials from members of the crusade; so Valentine mustn’t speak to anyone about this.

Valentine gives Father Salus sixty thousand francs — an enormous sum, essentially all her cash in the bank. She regrets her decision, as soon as the priest leaves. Not because she no longer believes that the Pope was kidnapped, but because — like everyone else in this story, except Amédée and Lafcadio — she is primarily worried about her own material wellbeing. So she jumps in a carriage and heads to the home of the Fleurissoires.

As noted, Arnica Fleurissoire isn’t bright. She doesn’t require any convincing to believe in the story of the kidnapped Pope, and promises that she and Amédée will give whatever money they can to Veronica, to help out.

Amédée, however, is something of a simpleton. Although his religious statuary business is successful, he himself hasn’t made much money from it. (That’s because his business partners — his close friend and romantic rival Gaston Blafaphas, and a Jewish friend, Lévichon — have engineered things that way. Lévichon doesn’t actually appear as a character in the book, but yes — Gide’s description of his shady business dealings is an anti-Semitic one. I think it also amuses Gide to imagine pious Catholics enriching a Jewish businessman by purchasing kitschy statues of saints.) Still, Amédée is a noble spirit — and he decides to head to Rome to see what he can to help free the Pope. He is a Don Quixote figure — foolish but lovable.

(Valentine and Arnica drop out of the story, here; their role in the plot is solely to send Amédée to Rome.)

Amédée has never traveled before, but his wife bundles him into the train with his shawl and umbrella and outdated tourist guide to Rome. Arnica tells him to get in touch with Cardinal San-Felice — who is a real priest, in Rome, not a con man. His frenemy, Gaston, claims that he’d gladly accompany him on this mission, but he can’t because… reasons. PS: Amédée’s story is all about physical comedy — a rail-thin, gawky, naive country bumpkin getting into one scrape after another in the big city. I’d suggest that Stephen Merchant play the role.

Meanwhile, Julius checks in with Anthime — who is living in squalor. Veronica got exactly what she prayed for, is Gide’s point: A truly pious husband. Anthime no longer works as a scientist; his hair and beard have grown out; he gives what little money he gets his hands on to the poor. “It is true that I am somewhat reduced — but what need have we of more? In the time of my prosperity I was astray; I was a sinner. Now, you see, I am cured.” He is, in fact, a saint. (Anthime and his wife drop out of the story, here; their role in the plot is solely to send Julius to the Pope.)

If Lafcadio is traveling with Julius, per my note at the end of the first act, then he is witness to this business with Anthime. What does he make of it?

Julius secures an audience with the Pope, in order to ask for the Church to help support Anthime — whose public disavowal of the Freemasons was a huge PR coup. Julius, as we know, is already questioning the values by which he’s always lived… and seeing how badly the Church has treated Anthime has really got him questioning his own faith.

At some point while he’s waiting to meet with the Pope, Julius bumps into Carola — whom he recognizes from Paris. We get the impression that Julius is tempted by her. He has led a blameless life, so this is further evidence of his midlife/existential crisis.

When Julius finally does get an audience, several days later, he’s never allowed to actually look at the Pope. The Pope sits on a throne beneath a concealing canopy, in a dimly lit room, and Julius is forced to prostrate himself. One of the Pope’s flunkies prods him in the back sharply every time he tries to look up at the throne.

If Lafcadio is traveling with Julius, does he, too, enter the Vatican? Is he waiting outside? If Genevieve is also traveling with these two — what’s her role at this moment?

Meanwhile, while Julius is attempting to get an audience with the Pope, Amédée’s quixotic adventure has turned into one long misadventure. Believing that his mission must be kept secret, he takes multiple trains — doubling back, jumping on and off at the last minute to throw off any pursuers. (Of course, there are none.) An inexperienced traveler, using outdated maps and travel guides, he ends up staying in terrible hotels where he is plagued by fleas, bedbugs, mosquitos. He rapidly spends what little cash he’s brought with him.

When Amédée arrives in Rome, he winds up in a hotel/whorehouse and meets… Carola. Gide describes this as mere coincidence, but perhaps for the purpose of the movie it would be better if Protos, who also lives in the hotel, sics Carola on Amédée? (Having been rebuffed by Lafcadio, Carola has moved to Rome and taken up again with her original lover, Protos. She is once more a member of the Millipede, Protos’s gang of con artists.) When Protos learns that Amédée has arrived from Pau, he’s worried that this has something to do with the sixty thousand francs out of which he’s just swindled Valentine; turns out that he’s right — Amédée has journeyed to Rome on a fool’s errand that could wind up exposing the Millipede’s con.

Carola seduces the hapless, virginal Amédée — he hardly knows what’s happening. He’s overcome with remorse, afterwards — because he believes that his purity was essential to his mission — which endears him to Carola. Although she’s supposed to keep Amédée from getting in the Millipede’s way, she begins to care about him — and seeks to protect him from Protos. She gives Amédée her distinctive cufflinks — the gift from Lafcadio — to wear, as a kind of protective charm.

Protos doesn’t want to kill Amédée, lest this result in an investigation that will disrupt the Millipede’s con. He can’t allow Amédée to do anything rash like attempt to gain entry to the Castle of St. Angelo (where the true Pope is supposed to be imprisoned), or meet with the Cardinal San-Felice. He decides to deflect Amédée, making him believe that he’s helping to rescue the Pope while staying out of trouble. He disguises himself as a priest, arranges to meet Amédée outside the Castle of St. Angelo, and warns the would-be rescuer not to hang around there; because the freemasons’ secret police are everywhere. Nor can he seek an audience with the Cardinal San-Felice. He tells him that the cardinal is under surveillance, too. However, once a week the cardinal disguises himself as a peasant, takes the train to Naples, and meets secretly with other members of the crusade.

Protos and Amédée take a train to Naples together — the former doing everything he can to make the latter paranoid about freemason spies. The two split up, when they arrive in Naples — Amédée stumbles his way through the town, as usual making a fool of himself, getting into all sorts of scrapes. Protos’s Millipede confederates, in Naples, are having a rather riotous luncheon — lots of wine drunk, lots of bottoms pinched. Amédée is shocked by this behavior, but the fake priest and cardinal contrive to look piously skyward whenever he catches their eye, as though signaling surreptitiously that they hate to behave this way themselves; however, to save the Pope, they must pretend for the moment to be simple peasants. (“Can you fail to understand that at moments we do not hesitate to clothe ourselves in the livery of sin and feign indulgence towards the most culpable of pleasures?”)

It’s an amusing scene, particularly when Protos’s fellow con man — the fake Cardinal San-Felice — actually gets a bit too drunk and starts adding extra twists to the Vatican Caves conspiracy theory, which the increasingly annoyed Protos must fold into the story he’s been telling Amédée on the fly. It’s a comedy improv scene — a “yes-and” exercise — with high stakes. (Protos and the fake cardinal remind me of Danny Ocean and Rusty Ryan, in the Ocean’s Eleven/Twelve/Thirteen movies: They’ve obviously worked together for years, and can pick up subtle cues from one another quickly.) The fake cardinal claims that not only the president of Italy and the freemasons are involved in the Pope’s abduction, but the Jesuits. (“Two great parties are facing each other — the Lodge and the Company of Jesus [the Jesuits]; and as we who are in the secret cannot get support from either of them without [revealing] ourselves, we have them both against us.”) What’s more, they warn Amédée to watch out for con artists — who “act in the name of the Crusade and rake in money which in reality ought to come to us.”

Amédée gets drunk, for the first time in his life. He vomits. He weeps. He confesses that he has lost his virginity to Carola. The two con men can barely suppress their laughter. The bogus Cardinal gives Amédée the job of cashing a check. Watched closely by the freemasons and the Jesuits, by the police and the swindlers, he complains, he can’t cash checks written to help them in their crusade. This one is from another of their victims — the Duchess of Ponte Cavallo — for six thousand francs. The payee has not been filled in; the fake cardinal has Amédée fill his own name in. He’s told to travel back to Rome, cash the check at the bank there, then bring the cash back to Naples. This enrages Protos, because Amédée is such a fool that he’ll probably screw up the operation, which means that Protos will have to don yet another disguise and follow him the entire time.

In fact, Amédée drunkenly sets out for the train to Rome, and Protos must quickly disguise himself — now he looks like a bank clerk or shop assistant — and trail him. (Will Amédée even be able to cash the check? He’s a nobody; the bank may turn him away.) Back in Rome, Amédée encounters Julius, who has just left his frustrating audience with the Pope.

Julius is possessed with an idea for a new novel, which he’s muttering about: “A creature of inconsequence! That’s going rather far, perhaps… and no doubt his apparent inconsequence hides what is, in reality, a subtler and more recondite sequence — the important point is that what makes him act should not be a matter of interest, that he should not be merely actuated by interested motives.” He is, of course, talking about how to transform Lafcadio into a literary character.

If Lafcadio is with Julius, at this moment, what does he make of this?

Julius is ecstatic, because his encounter with the Pope has caused him to finally renounce his faith. Now he is free — to write more daring novels, to express himself freely, to question conventional morality. He is interested in the natural aristocrat, who has “shaken his soul free from orthodoxy, from self-approval and self-interest.” Why should this person follow society’s rules? If such a person commits a gratuitous crime, how can we convict him? However, when he describes his strange encounter with the Pope to Amédée, and Amédée explains that he wasn’t actually meeting with the true Pope, Julius is crushed. If the true Pope is in captivity, then he can’t blame the Church for what has happened to Anthime, can he?

Protos, meanwhile, is trailing the two men. Recognizing Julius — who is a well-known public figure — he sees this as an opportunity to get that check cashed. He sends a message to Amédée, at the cafe where he and his brother-in-law are sitting — and tells him to take Julius with him to the bank. Perhaps Julius has been arguing with Amédée about the existence of this Crusade; the message’s arrival, out of the blue, is very convincing. Julius accompanies Amédée to the bank, where he co-signs the check, guaranteeing that Amédée is not a swindler. Amédée then boards a train for Naples; Protos, still in disguise, also boards the train.

Lafcadio is also aboard the train, in Gide’s novel. He appears out of nowhere, at this point, having vanished completely up until then. If, as I’ve suggested, Lafcadio has instead been traveling with Julius, then perhaps now he boards the train at Julius’s urging, to keep an eye on Amédée? If so, Protos must spot him — and recognize him as his old school companion….

Is Genevieve also on the train?

Only Lafcadio and Amédée occupy their train compartment. It is late at night, the train is nearly empty — though Protos is lurking somewhere aboard, unbeknownst to both men. Lafcadio is beautifully dressed, dapper; his hat is one that he has just had made — with his name inside.

He is tormented by the thought that he’s become a bourgeois do-gooder, helping old ladies carry sacks of potatoes and so forth… when he’s been training himself for years to be an immoralist, beyond good and evil. He thinks idly about shoving Amédée out of the train as it’s crossing a bridge.

True to his convictions and training, Lafcadio leaves this momentous decision up to chance. As the train crosses the bridge, he decides that if he can count up to twelve without seeing a light in the countryside, he won’t do it. He counts to nine, sees a light, opens the door and shoves the sleeping man out!

As he plunges to his doom. Amédée snatches Lafcadio’s hat off.

Lafcadio searches the dead man’s coat pockets, and finds the envelope full of cash — which he leaves there.

In Gide’s novel, Lafcadio is astonished to see Julius de Baraglioul’s name on the man’s train ticket. He finds a letter from Arnica instructing the dead man to meet with Julius in Rome. What’s going on? He decides to head back to Rome, to find out the whole story from Julius. In our movie adaptation, perhaps he heads to Rome to say farewell to Genevieve?

Protos, meanwhile, has witnessed the whole thing. He gets off the train at the next stop, and makes his way down the embankment to the body.

Third act:

As the third act begins, we are in Rome on the following day. The afternoon papers suggest that Amédée’s death may have been accidental — for if it had been a robbery (a crime with a motive), the thousands of francs wouldn’t have been left. Lafcdio learns from the newspaper that the man was wearing unusual cufflinks — which he recognizes as the cufflinks he gave to Carola. The hat has been found… but someone has cut his name out of it! Why?

Lafcadio finds Julius in a state of agitation. His point of view has changed completely since he first met the young man. He has also just seen, in the Roman newspaper, that his brother-in-law Amédée was murdered on the train.

Julius wants to live a freer life. He mentions Carola to Lafcadio, how beautiful she’s looking these days.

“You find me in a great state of agitation. I’m at a turning-point of my career. My head is burning and I feel, as it were, giddy all over, as if I were going to evaporate.”

Julius tells Lafcadio about his new book: “You can’t imagine, because you aren’t in the trade, how an erroneous system of ethics can hamper the free development of one’s creative faculties. So nothing is further from my old novels than the one I am planning now.” Until now, he confesses, what has hindered him from writing in a free manner “have been impure considerations — questions of a successful career, of public opinion.”

He tells Lafcadio that “The hero is to be a young man whom I wish to make a criminal.” Lafcadio is not impressed, but Julius seems to believe that this is very daring of him. (Of course, this is doubtlessly Gide poking fun at himself for having qualms about writing Les caves du Vatican.)

He wants to write a crime novel in which the criminal has no motive. “I mean to lead [this character] into committing a crime gratuitously — into wanting to commit a crime without any motive at all.” This young man, Julius says, “acts almost entirely in play, and as a matter of course prefers his pleasure to his interest.” Also, “he takes pleasure in self-control” (Lafcadio adds “to the point of dissimulation” — that is, he controls his desire to show off his superiority to others, by pretending to be quite ordinary and dull.) This character loves risk, and is highly curious.

This is a character sketch of Lafcadio himself: “I imagine him training himself. He is an adept at committing all sorts of petty thefts. … The only opportunities that tempt him are the ones that demand some skill — some cunning. [Lafcadio: “And which run him… into some danger.”] “He doesn’t want to appropriate things, but finds it amusing to displace them surreptitiously. He’s as clever at it as a conjurer.”

“Just think!” exclaims Julius. “A crime that has not motive either of passion or need! His very reason for committing the crime is just to commit it without any reason.” He is “at the mercy of the first opportunity.” Julius insists that such a man shouldn’t even be considered a criminal. Pointing to the headline about Amédée, he suggests that the murderer — who didn’t take the six thousand francs that Amédée was carrying — could serve as a real-life example of this fictional character.

Although Julius doesn’t realize it, he is absolving Lafcadio of blame in Amédée’s murder.

In Gide’s novel, Lafcadio is surprised to discover that Amédée is Julius’s brother-in-law; in the adaptation that I’m suggesting, surely he would have known this? Perhaps that would have made his disinterested act even more shocking?

As Julius reads the newspaper account, he mentions that Amédée was wearing a single cuff-link — its description exactly matches the cufflinks that Lafcadio gave to Carola. So now Lafcadio knows that Carola must have had something to do with Amédée.

The newspaper also reports that the dead man was found clutching a brand-new hat, out of which the owner’s name has been neatly cut. This staggers Lafcadio — did someone witness the crime, climb down to the body and remove the evidence linking Lafcadio to the murder? But why not take the whole hat?

Meanwhile, Julius believes that he knows why Amédée was killed. Since the motive wasn’t robbery, it must be the Masons, or the Jesuits, or one of the various players in the abducted-Pope conspiracy. He hadn’t really believed Amédée’s conspiracy theory, but now he does. Also, this insight instantly restores Julius’ lost faith. “His death comes just in time to cut me short in a career of irreverence — of blasphemy. His sacrifice has brought me to reason.”

Julius instantly abandons his plan to write a book about a crime without motive. The motive for this crime was to silence Amédée, to keep him from revealing the conspiracy against the Pope. Julius now decides that e must pick up where Amédée left off, and join the crusade to save the Pope.

Lafcadio had wanted to confess everything to Julius — who in in his previous frame of mind would have absolved and even praised him for the murder. But now he can’t. He takes the one piece of evidence he’s saved from the crime scene — the ticket, in Julius’s name, that Amédée was carrying on the train — and leaves it on Julius’s apartment table. It is a confession of guilt.

When Julius returns home in the evening and discovers the ticket, he is terrified — he takes it as a warning from the conspirators.

Carola also approaches Julius — she’s learned from the papers that Amédée was Julius’s brother-in-law. Upon hearing of Amédée’s demise, Carola immediately suspects Protos — who wanted to kill Amédée. She goes to the police, and turns Protos in. Carola tells Julius that she’s turned in Amédée’s murderer; meanwhile, the lustful Julius is pursuing her around a table. But Carola is a changed woman — she rebuffs him, and leaves.

Julius sends Lafcadio to bring Amédée’s body back to Rome. He is in a disturbed state of mind — Gide describes it as ennui. He’s finally committed a great, unmotivated act — and it has left him troubled, hopeless, joyless. He’s lost his bravado and dash. He walks up and down the train’s corridor “harassed by a kind of ill-defined curiosity and vaguely seeking he knew not what new and absurd enterprise in which to engage.” He is also troubled by the fact that someone cut his name out of the hat left in Amédée’s dead hands.

In the train’s dining car, he encounters Julius’s wife Marguerite, and their younger daughter, Julie, dressed in mourning clothes, who have come to Rome for Amédée’s funeral. (In Gide’s book, Lafcadio hasn’t met these two yet; in my suggested adaptation, they would have met while Lafcadio was working as Julius’s secretary.) Anthime and his wife are also aboard the train, for the same purpose. Also, Arnica and Blafaphas.

He also meets a comical old law professor — Monsieur Defouqueblize — who is unsteady on his feet, near-sighted, dropping things… Lafcadio kindly takes him in hand, and sits with him at dinner. While they’re eating, Carola’s cufflink — the missing one of the pair — appears as if by magic on Lafcadio’s plate. He and Defouqueblize have a bizarre conversation, about what it takes for an honest man to turn into a rogue.

Back in their train compartment, Defouqueblize reveals his identity — it is Protos! Truly a master of disguise. (Note that Louis Feuillade’s popular Fantômas serials — Fantômas I: À l’ombre de la guillotine, Fantômas II: Juve contre Fantômas, etc. — were first screened at exactly the time Gide was writing and publishing this novel.) If he expects Lafcadio to be dumbfounded, he is disappointed — Lafcadio is always ready for anything. Still, Protos takes the piece of leather from Lafcadio’s hat, out of his pocket — it was he who’d taken it, in order to blackmail Lafcadio and gain power over him. He’s always wanted to control Lafcadio, and this seems to be his opportunity.

Lafcadio asks how much money he wants for the piece of leather. Protos says he doesn’t want money. He’s always resented Lafcadio’s decision to “escape from the social framework” (bourgeois society, rules and laws, morality) while at the same time steering clear of Protos’s criminal underworld. Lafcadio’s consummate criminal skills, used for nothing more than harmless pranks, strike Protos as a terrible waste. He was enraged that Lafcadio didn’t rob Amédée of the six thousand francs.

He threatens to turn Lafcadio over the police: “For the future you are in their power — or ours.” He wants Lafcadio to blackmail Julius — to get Julius to pay a fortune to Protos’s gang, otherwise Lafcadio will be named the murderer of Amédée — which will destroy the Barraglioul family’s reputation.

Lafcadio reject Protos. “Go and inform [the police]. I am ready.”

Julius meets his family at the station. Marguerite informs him that her cardinal friend has told her, in confidence, that Julius will indeed be elected to the Academy. Julius has now completely reverted to his old ways. “Faithful to you [his wife], to my opinions, to my principles!” he smugly announces. “Perseverance is the most indispensable of virtues.”

At Amédée’s sparsely attended funeral, it’s clear that no one cared much about poor Amédée — except Carola, who is snubbed by Julius. Even Arnica seems quite happy to be comforted by Blafaphas, the faithless friend. After the funeral, Julius tells Anthime that the true Pope isn’t on the throne. Anthime loses his saintly composure — “if after all I’ve sacrificed my fortune, my position, my science…” He announces his intention to rejoin the Masons, to take up the cudgels against the Church again. Julius is surprised by this turnabout — until he learns that Anthime’s rheumatism has returned.

So everything returns to exactly the state of equilibrium that existed at the beginning of the story. Julius and Anthime’s adventures into, respectively, atheism and piety are over.

But what of Protos and Lafcadio? The police surround the hotel in which Protos and Carola live. When he finds out that she betrayed him, he strangles her — the police catch him in the act, and he is arrested. Protos is also charged with Amédée’s murder.

Lafcadio is actually discontented that he got away with Amédée’s murder. His victory was too easy. So he approaches Julius and confesses. Julius, the bourgeois hypocrite, encourages him not to say a word, to allow Protos to take the blame.

Genevieve approaches Lafcadio’s room that night. She has heard the whole conversation between Lafcadio and her father. Lafcadio tries to send her away, but she won’t go. She loves him. They spend the night together. In the morning, Lafcadio wakes up — she is in his bed, outside he can hear a police bugle. Will he rejoin society? Will he give himself up?

FINIS

Gide described Les caves du Vatican as a sotie — that is, a satirical play exposing humankind’s foolishness. It is that — in it treatment of the Péterat sisters and their husbands.

But it’s more than that, isn’t it? If this had merely been a comedy about a con artist whose machinations cause a self-satisfied religious man to lose his faith, and a self-satisfied scientist to become pious, then it would have been merely an amusing satire. The extraordinary character Lafcadio, a high-spirited trickster who refuses to choose sides between order and chaos, good and evil, throws a monkey wrench into the works of what might have been merely a light-hearted entertainment. He’s a disruptive force, frustrating the reader’s expectation of amusement and the self-validating feeling of superiority that comes with amusement. We’re left aghast, astonished, unsure whether to laugh or cry.

Les caves du Vatican is an extraordinary adventure, written by a highbrow French author inspired by lowbrow pulp fiction. A few years after the publication of this book, a young André Breton would write, to fellow absurdist litterateur Tristan Tzara, “You can’t imagine how much André Gide is on our side.” That’s exactly right: It’s an anti-middlebrow tour de force.

The book hasn’t aged well, in certain key respects. I’ve tried to suggest a few possible remedies. Whether it were to be adapted as a movie or a TV miniseries, today’s audiences would embrace Gide’s difficult, terrible, wonderful sotie.

Hollywood, let’s make this happen.

LISTEN, HOLLYWOOD: Michael Innes’s FROM LONDON FAR | P.G. Wodehouse’s LEAVE IT TO PSMITH | Peter Dickinson’s CHANGES TRILOGY | Robert Heinlein’s GLORY ROAD | Poul Anderson’s THE HIGH CRUSADE | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s TARZAN AND THE FOREIGN LEGION | G.K. Chesterton’s THE NAPOLEON OF NOTTING HILL | Michael Innes’s THE JOURNEYING BOY | Alfred Jarry’s EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN | André Gide’s THE VATICAN CAVES [LAFCADIO’S ADVENTURES].

Also see Josh Glenn’s SHOCKING BLOCKING series: It Happened One Night (1934) | The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) | The Guv’nor (1935) | The 39 Steps (1935) | Young and Innocent (1937) | The Lady Vanishes (1938) | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) | The Big Sleep (1939) | The Little Princess (1939) | Gone With the Wind (1939) | His Girl Friday (1940) | The Diary of a Chambermaid (1946) | The Asphalt Jungle (1950) | The African Queen (1951) | A Bucket of Blood (1959) | Beach Party (1963) | For Those Who Think Young (1964) | Thunderball (1965) | Clambake (1967) | Bonnie and Clyde (1967) | Madigan (1968) | Wild in the Streets (1968) | Barbarella (1968) | Harold and Maude (1971) | The Mack (1973) | The Long Goodbye (1973) | Les Valseuses (1974) | Eraserhead (1976) | The Bad News Bears (1976) | Breaking Away (1979) | Rock’n’Roll High School (1979) | Escape from Alcatraz (1979) | Apocalypse Now (1979) | Caddyshack (1980) | Stripes (1981) | Blade Runner (1982) | Tender Mercies (1983) | Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life (1983) | Repo Man (1984) | Buckaroo Banzai (1984) | Raising Arizona (1987) | RoboCop (1987) | Goodfellas (1990) | Candyman (1992) | Dazed and Confused (1993) | Pulp Fiction (1994) | The Fifth Element (1997) | Nacho Libre (2006) | District 9 (2009).

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.