STUFFED (34)

By:

May 16, 2019

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste. STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

The Enlightenment, an 18th-century European fad that brought us such notions as freedom of religion, separation of church and state, and life, liberty, and the pursuit of property (or happiness, here in America), not to mention democratic government, a certain skepticism of accepted wisdom, and toleration of our fellow man — all of which either failed to be implemented or have gone by the wayside, some of them fairly recently — was, as is now apparent, a failure. Its lasting legacy, from the vantage point of 2019, seems to be the imaginary but widely influential idea of free-market capitalism, and the widely internalized prison surveillance system (and metaphor for 21st century life) known as the panopticon.

However, the Enlightenment was not always as leadenly serious as is often reported. No, once in a while it provided fanciful answers to questions that hadn’t even been asked yet.

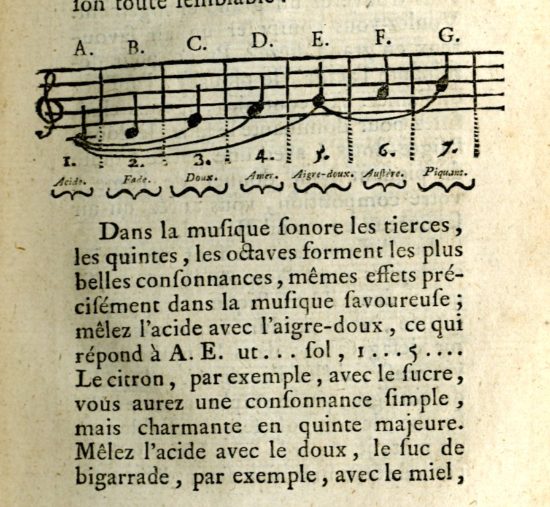

This last thread of the Enlightenment is nowhere more apparent than in Polycarpe Poncelet’s Nouvelle Chymie du Goût et de L’Odorat (New Chemistry of Taste and Smell). In this 1755 book, Poncelet describes his theory that taste functions just as music does, with flavors either being in harmony with each other or combining in unpleasantness. He believed that the correspondence with music was so great that you could actually represent them on a musical staff: A – sour, B – insipid, C – sweet, D – bitter, E – harsh, F – bittersweet, G – piquant. In his book’s second edition (1774), he describes a “taste organ” that does exactly that, combining flavored liquids that flow into a reservoir as keys are depressed and bottles opened. Play a little tune and have a taste, the mysteries of the senses elucidated in a series of flavors commingled in a structured, repeatable way.

Of course, it didn’t really go anywhere — and even Poncelet admitted that he gamed the flavor mixtures a little, putting tastes together that he knew would be complementary rather than truly allowing the music analogy to play out.

Even if in reality it seems to have disappeared, the organ does appear now and again in fiction, most famously in Huysmans’s 1884 decadent novel À rebours (translated as Against the Grain). Huysmans’s protagonist, Jean des Esseintes, invents a similar device that he eventually masters in order to play symphonies in his mouth. Esseintes has retreated from the bourgeois world, which he feels alienated from, into an idealized realm of the senses; he immerses himself in color choices, interior decoration, and becomes, like his jewel-encrusted tortoise, beautiful but immobilized by affectation. À rebours was famous enough in its time to be ridiculed at Oscar Wilde’s trial as “sodomitical”.

Symbolist poets — Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Mallarmé — transformed these sorts of ideas into poetry, taking the only recently medically explored field of synesthesia and using its concepts to describe obliquely phenomena from the sensory to the philosophical that are difficult or impossible to describe directly. The idea of a melding musical notation with flavors has poked its head up now and then, but each time failed to catch on. Willy Wonka should have had one, certainly, but somehow didn’t.

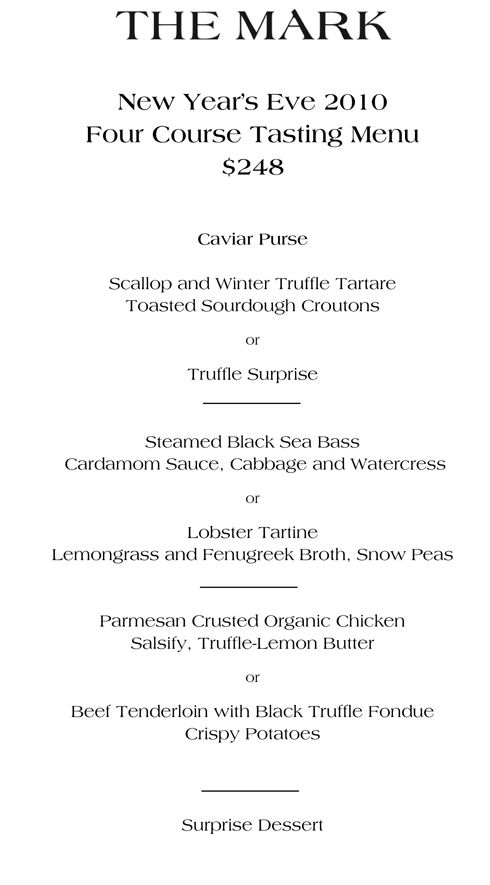

Nowadays, nobody even seems to be thinking about taste organs. Firing cars into outer space, advertising algorithms, racist facial recognition, securitizing debt obligations in new and dangerous ways, sure — but taste organs are off somewhere with our jetpacks and great public transportation, gathering dust. The closest thing we have now, though it is the difference between giving someone a clarinet and giving them a classical music album, is the now ubiquitous tasting menu. The conceit of the proper tasting menu is that the chef is going to tell you a story with flavors, perhaps play your taste buds like a musical instrument? The metaphor is muddled, but the ideas motivating the enterprises are the same — flavor can be used as a form of expression. The difference is that it’s not under the user’s control — you’re experiencing someone else’s taste symphony.

Which is fine, as far as it goes, and would be just another choice except we never got our taste organ, just this debased relic from the Enlightenment fueled by the cult of personality and our weird lingering obsession with rich people. It’s the itch of the American dream, a phantom limb that still, impossibly, throbs with dumb hope.

As tasting menus have gone from a $500 treat for the wealthy to a $150 night out for the aspirational, the conceit has only become more articulated. Restaurants like Tom Sellers’s Story in London are unselfconsciously portraying the tasting menu as an exercise in flavor as symphony, as narrative. There is a restaurant called Story in Kansas City with a $75 tasting menu, The Musket Room near SOHO in NYC that has a “Short Story tasting menu” for $95, and so forth.

NY Times restaurant reviewer Pete Wells, in 2012, poked holes in some of the problems with the hegemony of the tasting menu — though this was before breaking the $100 barrier was too common. But what I am concerned with is our sudden desire to be dictated to, our eagerness to put ourselves under the thrall of some chef or another and let them feed us a story. In the 1900s we had the chafing dish; in 1939, at the Swedish Pavilion of the World’s Fair in New York, the Smörgåsbord was introduced and immediately carved a place in the American imagination. The buffet, upscale, downscale, Golden Corral scale, has always been something that needed no explanation in the U.S. Even the salad bar (the sad, shrunken, 1980s version of the buffet), perhaps a reaction to the coke-infused junk bond Miami Vice era that spawned it, offered an array of choices that harmonized with the American character.

So what happened? Why the sudden hankering for this autocracy of the tasting menu? Are we just exhausted from food’s ubiquity? Soylent — a cultural pertuberance (proterbation?) that is the tasting menu approached from the opposite direction, an autocracy of eating instead of taste, just recently expanded their food-replacing beverage product line to include food-replacing bars.

Years ago I wrote (at some length, over and over again) about condiments and democracy. I was half kidding, and, again, I half kid about the relationship between the “taste organ”, tasting menus, and our increasingly welcoming attitude towards fascism. Though I even went on New Hampshire NPR in 2015 to warn that our reliance on sriracha was going to bring down our republic as surely as Rome’s obsession with fish sauce brought down theirs. I was roundly ignored, and you see where that got us. And this does comes just as what is perhaps the most central Enlightenment ideal — skepticism — has really taken it on the chin. The internet (special thanks to those deep thinkers at Facebook) and Freakonomics has turned everyone into an outside-the-box, counterintuitive genius. We are so skeptical that we’ve wrapped around and become ingenuous idiots instead, susceptible to the most obvious ploys imaginable because we live in constant fear of being cleverly led astray.

As tasting menus move downmarket (the wealthy were born to rules and order, hugging them close lest they, or their children, someday have to mingle with the unwashed, so I’m not concerned with their love of authority), I worry that what we are saying over and over again, is: “Everything is hard, and confusing, and weird, and terrible, just tell us what to do, please.”

So, even if just to humor me, maybe skip the tasting menu and buy some weird shit and cook it from home once in a while.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.